Hope for everything. Expect nothing.

On the 100th anniversary of Eugene Debs’ presidential campaign from an Atlanta prison

One hundred years ago, the American socialist Eugene Victor Debs was writing a plea to voters from a crowded, stinking cell at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary.

He was running for president from behind bars. He had no illusions about his chances:

There is one thing I know on the eve of this election. I shall not be disappointed. The result will be as it should be. The people will vote for what they think they want, to the extent that they think at all, and they, too, will not be disappointed.

In my maturer years I no longer permit myself to be either disappointed or discouraged. I hope for everything and expect nothing. The people can have anything they want. The trouble is they do not want anything. At least they vote that way on election day.

I read Ray Ginger’s meticulous 1947 biography of Debs, The Bending Cross, at a leisurely pace this year, hoping to gain some insight into his 1920 presidential run. I finished it this week and caught myself shedding a few tears. Debs had that effect on people in his own time, too.

Socialists aren’t supposed to have heroes, and I’m not going to idolize Debs today. He certainly wouldn’t want that. “If you are looking for a Moses to lead you out of this capitalist wilderness,” he once said, “you will stay right where you are.”

But I am struck by the fact that we don’t have a Debs for our time. We have a handful of prominent voices speaking out for the working class, but the working-class power structures that pushed Debs into the spotlight no longer exist in any meaningful way in this country. Our labor unions are weak, our anti-war movement is defanged, and a general fog of post-Cold War “capitalist realism” seems to have narrowed our imagination about a better future.

I still want to believe, as Debs did, that another world is possible. I don’t expect it, but I hope for it and I’m willing to try.

***

Debs had an instinctual and ever-shifting worldview, starting out as a railroad worker and entering the world of politics via his decades of struggle as a railroad union organizer. The closest thing he had to a religious scripture or formative political text was his namesake Victor Hugo’s novel Les Miserables. It was through conversation, not reading, that he became a trade unionist, then an industrial unionist, then a firebrand of international socialism.

For a socialist living in the United States, he was immensely popular at times. He drew adoring crowds from big cities to mining towns to his hometown of Terre Haute, Indiana, and even won the affection of his jailers every time he went to prison.

Debs was a romantic. Reading Ginger’s biography of him, I was struck by how often flowers appeared during the darker moments of his life.

The first time he went to prison in 1894, Ginger wrote, “Each morning Debs placed a fresh carnation in his buttonhole.” I love that.

He was serving time for his efforts to organize a boycott and strike against the Pullman Palace Car Company. George Pullman had slashed his workers’ pay while taxing them with rent and fees in the company town of Pullman, Illinois, leaving spouses and children starving in the streets. While Debs was revered among railroad workers for his leadership during the strike, the New York Times editorial board had dubbed him “an enemy of the human race.” It was during this low ebb of his career that socialists including Victor Berger evangelized him in prison and converted him to their cause.

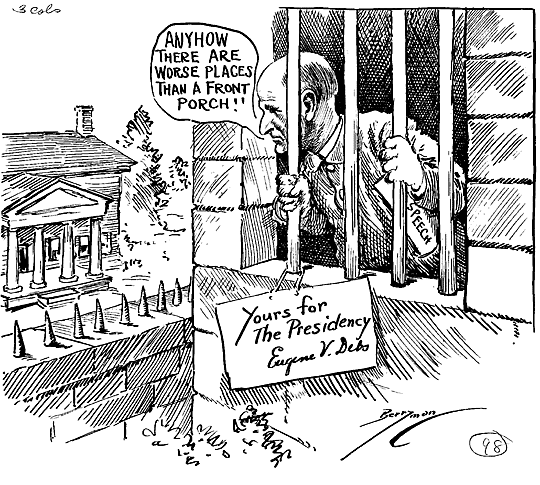

Political cartoon by Clifford K. Berryman, Oct. 11, 1920. Public domain.

The second time Debs went on trial, in 1918, it was for violating the U.S. wartime censorship law known as the Sedition Act. A fierce opponent of U.S. involvement in the first World War, he had given a speech in Canton, Ohio, that the bourgeois courts interpreted as urging resistance to the military draft.

He seemingly willed himself into prison. Thousands of his comrades had been rounded up and jailed simply for being socialists, communists, or anarchists, and he had written in a letter to one of them, “I shall feel guilty to be at large.” He wrote a number of speeches and broadsides that delivered variations on the theme of “No war but the class war” before the censors seized on the one unremarkable speech in Canton as a pretense to arrest him.

Debs offered no resistance when the authorities came for him. He all but thumbed his nose when President Woodrow Wilson called him a “traitor to the country.” Again, Ginger noted that flowers were all around.

There were petunias growing in a planter box on his front porch in Terre Haute as he awaited trial with his wife Kate and brother Theodore.

There was a young girl at his sedition trial who, after hearing his closing speech to the jury, handed him a bouquet of red roses and then fainted.

And after he was found guilty, on the final night at home before his prison sentence began, his parlor was decorated with a “gigantic display” of American Beauties — a gift from an elderly Irish-American neighbor who prayed for him daily.

***

I think of Eugene Debs with flowers all around him. Even in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta, he noticed a flower garden just outside his cell.

“Really, this place is not so bad,” Debs told his friend Clarence Darrow during a visit. “I look at that garden of flowers. There are bars in front, I know — but I never see the bars.”

At the time he made this whimsical comment, he was an old man with a bad back, doing damage to his heart and kidneys on an insufficient diet of prison slop. Outside the bars and beyond that little flower garden, the world was growing objectively dim. Federal authorities were violently suppressing union actions, the socialist movement was fractured by internal quarrels, and nationalist vigilantes and gangs of white supremacists were emboldened to launch campaigns of domestic terror.

In the middle of all that doom, Debs considered the flowers. I don’t know if he ever latched on to the “Bread and Roses” slogan of suffragettes and textile mill strikers in the 1910s, but I think he would have appreciated the simplicity of it. The fight was always about more than bread, more than survival. It was about ushering a little bit of dignity and beauty into the world. Flowers are extravagant and impractical and necessary.

Sketch of Eugene Debs sitting on his porch during a 4th of July parade in Terre Haute with petunias in bloom. Published in The Liberator, September 1918.

I am writing all of this in the final week before Election Day 2020, one hundred years after Debs’ final run in 1920. I don’t have much to say about this election. I’m not trying to convince you to vote third-party or write in the ghost of Eugene Debs. I’m just trying to picture an emancipatory agenda that goes beyond Nov. 3 and whatever Bush v. Gore-level chicanery the Republican Party may attempt in its wake. I am not pinning my hopes on the Democratic Party.

On the five occasions when Eugene Debs ran for U.S. president, he seemed more interested in riling up workers at his stump speeches than in actually taking office. The closest he came to a win was in 1912, when he earned 6% of the popular vote but won no states in the electoral college.

He won nearly a million votes from an Atlanta prison in 1920, carrying 3.4% of the popular vote, and the presidency went to the Republican Warren G. Harding. At the urging of numerous labor unions and groups of veterans who returned from the war horrified by the jailing of political dissidents, Harding commuted the sentence of Debs and 23 other political prisoners, releasing them on Christmas Day 1921.

Debs was close to death, and he never ran for president again. He and his fellow inmates had notched a few victories along the way, though: They had convinced the corrections officers at Atlanta Federal Penitentiary to stop enforcing mandatory chapel attendance, and Debs had built a bridge of solidarity with the other prisoners he met. At the time of his death in 1926, he had just attempted to register to vote after having his franchise revoked under the Sedition Act. He wanted to restore voting rights to everyone who had endured prison like himself.

Today incarcerated people make up a larger portion of our population than in any other country on earth, and the vast majority here are denied the right to vote. We have backpedaled in the century since Debs’ last campaign.

There is no anti-war party with representation in either chamber of the legislature. Labor unions are on the ropes after decades of kneecapping by the executive branch and the courts. The club of plutocrats who Debs battled during the Gilded Age is now more entrenched and powerful than ever.

And we have no Eugene Debs because we have no working-class movement to produce a Eugene Debs. I have great respect for Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Bernie Sanders, and the Revs. William Barber II and Liz Theoharis, but we still lack a nationwide base of power from which to challenge capitalism.

We can build it again, though. Debs said it best in a speech to the Indiana Federation of Labor in 1925:

This world respects as it is compelled to respect. Develop your own capacity for clear thinking. Unorganized, you are helpless, you are held in contempt. Power comes through unity. Organization or stagnation, which will you take?

I am heartened by our local DSA chapter, which has grown by leaps and bounds this year and found new outlets for solidarity. I take courage from the nurses who just won a historic union vote in Asheville, North Carolina, and from the journalists in Beaufort who just unionized the first local newsroom in South Carolina.

On the global stage, I rejoice with the Bolivian people who just walloped the U.S.-backed right-wing coup government in an election. I’m awed by the Chileans who won a plebiscite this month to replace the constitution that was written under the rule of U.S.-backed dictator Augusto Pinochet.

So I am not all doom and gloom, regardless of the election’s outcome. I hope for everything. I expect nothing.

***

If you liked today’s issue, you might appreciate this interview I did with a member of the Asheville nurses’ union, this other interview I did with reporters from the newly unionized newspaper in Beaufort, or this piece I wrote about a preacher’s truth-telling role in the Pullman Strike.

The Bending Cross is available to order via the Brutal South Bookshop page. It’s long and unapologetically romantic, but I found it to be a rewarding read.

If you’re in the Charleston area and haven’t joined yet, our little DSA chapter is in the middle of a recruitment drive and we’d love to have you. Not to brag, but we’re currently on the leader board in a friendly national recruitment competition. Click here to join; holler at me if you have any questions.

The pin at the top of the page is mine. I got it from the Debs Foundation.

Twitter // Bookshop // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts