The real debate is in the streets

The Poor People's Campaign is an antidote to political despair

I have never watched a presidential debate and found it to be a more worthwhile use of my time than riding a bike, making paper snowflakes with my kids, or watching Vanderpump Rules for the third time.

It is not hard to see the debates for what they are: catty pageants that pair well with advertising.

Like Don Draper on Mad Men, the people running political campaigns realized a long time ago that they had to sell voters on a feeling about a candidate and not on a set of value propositions. Cults of personality are almost inevitable in this environment.

So whenever the TV people are having another debate, I look for signs of hope anywhere but the debate stage.

In 2012 I found Occupy Charleston protesters sneaking their way into the North Charleston Coliseum during a Republican primary debate, hoping to somehow unfurl a banner onstage that read “MONEY OUT OF POLITICS.” They didn’t pull it off, but I was glad to see them try.

In 2016 a crowd led by fast-food workers flooded the streets outside a Democratic debate in downtown Charleston. They were demanding a $15-an-hour minimum wage and union recognition, and they carried a banner: “COME GET OUR VOTE.” (One candidate did come out into the street with a bullhorn and lend his support, by the way: Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont.)

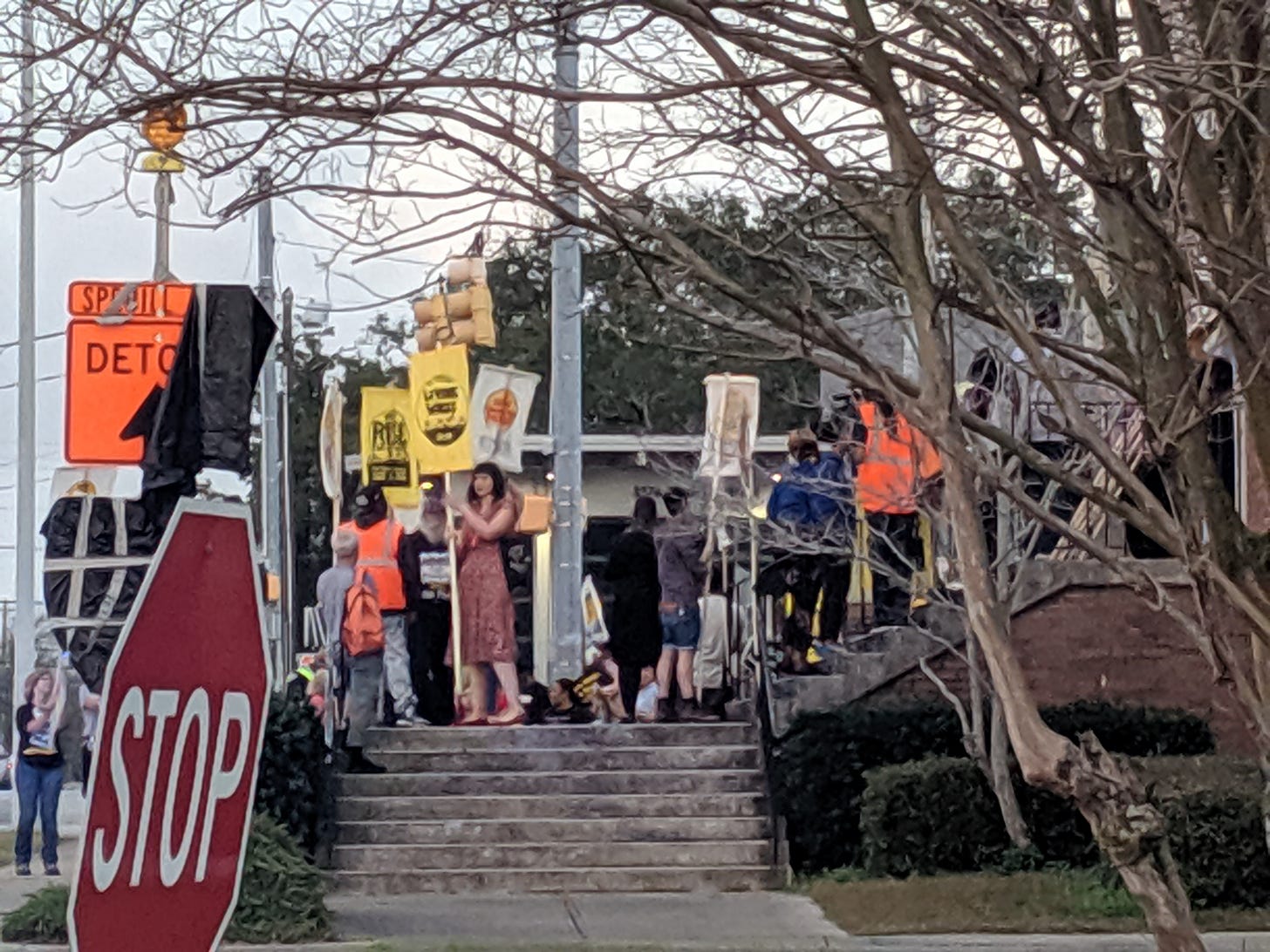

Tuesday night in Des Moines, the Poor People’s Campaign was marching outside the Democratic debate. I wasn’t there, and I wasn’t watching on TV, but I stood with members of the Poor People’s Campaign Monday night when they came to my city. Out in the streets of North Charleston and in the sanctuary of a church, we hoisted our own banners:

“A NEW AND UNSETTLING FORCE FOR LIBERATION.”

“FIGHT POVERTY, NOT THE POOR.”

“YOU ONLY GET WHAT YOU’RE ORGANIZED TO TAKE.”

The Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival is an anti-poverty campaign that entered the national spotlight with a series of direct-action protests at statehouses in 2018. Drawing inspiration from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s 1968 movement of the same name, the Poor People’s Campaign seeks to combat what Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. called the “triplets of evil”: racism, materialism, and militarism

I volunteered to direct traffic in the church parking lot, so I didn’t get to join the march that wended its way through the city. When the marchers arrived at Cherokee Place United Methodist Church, I took off my reflective safety vest and found a spot in the pews.

The rally in the muggy sanctuary was unlike any church service I’d been to. We sang spiritual songs and joined hands in prayer, but the bulk of the time was devoted to lamentation.

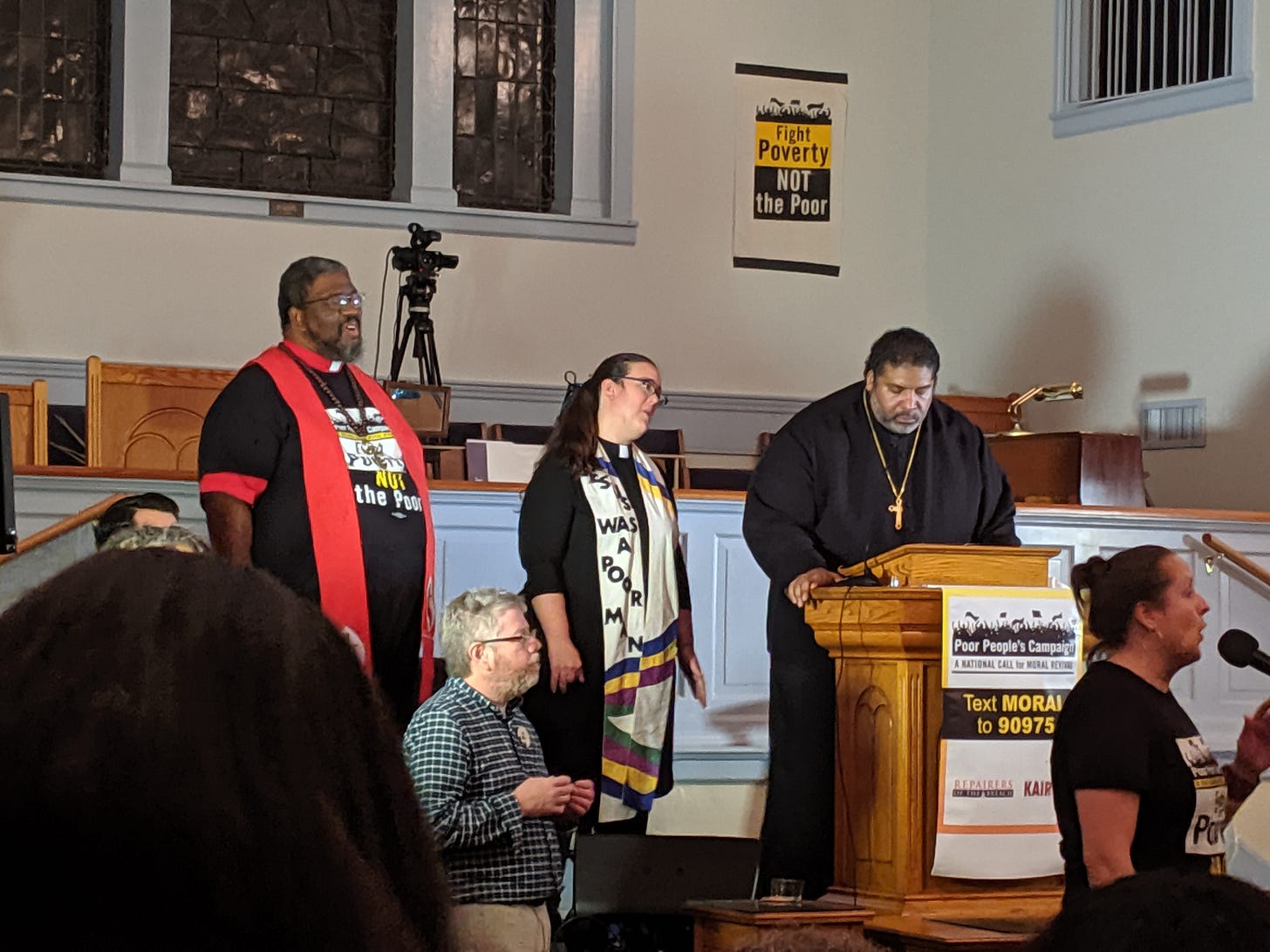

What was so refreshing about the Poor People’s Campaign, as opposed to every political debate I have ever seen, was that it did not revolve around the personal magnetism of its leaders. The Revs. Liz Theoharis and William Barber II were certainly recognizable from press photos, but they ceded much of the evening to gospel singers and speakers testifying about their experiences with poverty.

Christine Riccio talked about living in a tent city until the former mayor of Charleston chased the homeless people out of town. Erica Fielder talked about the pain of being married to an incarcerated person. Local journalist Fernando Soto talked about his parents’ decision to flee the wreckage of the U.S. drug war in Ciudad Juarez.

In the pews with my friends from church, we clapped awkwardly after one of the testimonies, but Rev. Barber asked us to hold the applause.

“This shit ain’t pretty,” he bellowed from the aisle. Instead he led us in a chant: “Somebody has been hurting our people … it’s gone on far too long … and we can’t be silent anymore.”

Monday night’s rally was a lamentation without a pat answer at the end, but it gave me reason to hope. I met new people doing exciting work for justice. I saw what solidarity could look like. It was a far cry from CNN.

***

If you would like to join the Poor People’s Campaign, go to poorpeoplescampaign.org and find out how you can get involved in your area.

On a related note, if you are in South Carolina and have been following the teacher movement here, be sure to take a look at this petition against Senate Bill 419. It’s an education bill, and its authors are seeking to ram it through this week despite repeated protests from teachers from across the state. Follow SC for Ed on Facebook and Twitter or check out their website for more updates.

Finally, I want to close out this week’s newsletter with a passage from Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death:

It is a sobering thought to recall that there are no photographs of Abraham Lincoln smiling, that his wife was in all likelihood a psychopath, and that he was subject to lengthy fits of depression. He would hardly have been well suited for image politics. We do not want our mirrors to be so dark and so far from amusing. What I am saying is that just as the television commercial empties itself of authentic product information so that it can do its psychological work, image politics empties itself of authentic political substance for the same reason.

Postman was commenting on the shift from a text-based to an image-based culture — from the sprawling elocution of the Lincoln-Douglas debates to the clipped spectacles of the televised Nixon-Kennedy debate and beyond. There is of course no going back.