The church, the boss, and the company town

How a pastor helped expose the abuses of a “model” community

Pullman was the model town of the future. Tourists visiting Chicago for the 1893 World’s Fair were invited to ride the train south to Pullman, ooh and ahh at its ornate facades, and envision a future free of urban slums and labor strife.

Outside the modern streamlined factory of the Pullman Palace Car Company stood a fashionable Romanesque arcade building and a Gothic Revival church. Workers lived in townhouses with indoor plumbing and gas. The town library boasted thousands of books of poetry.

Pullman sprang from the earth according to one man’s plan. George Mortimer Pullman planned all construction (employing the architect Solon Spencer Beman), envisioning an industrial utopia under his complete control. The Pullman Palace Car Company was the only employer and the only landlord in the town. Everything bore his name.

The workers knew what life was like behind the facade. Their wages trailed behind their union counterparts in other cities, rent was inflated because their landlord had a monopoly on land, and their employer took bites out of their paycheck through ever-increasing fees. When the Panic of 1893 plunged the country into depression, workers saw their wages slashed while their rent remained the same. They worked long hours while their families starved. If they spoke out, they risked losing their jobs and their homes all at once.

There was almost no one in a position of power to challenge George Pullman. The company installed loyalists in town government and openly intimidated opposition candidates. Even the American Railway Union, which ostensibly represented the workers, was more or less oblivious to conditions in Pullman until dissent boiled over in 1894.

At least one community leader was paying attention, though: Rev. William H. Carwardine, pastor of Pullman Methodist Episcopal Church. Carwardine makes an important cameo in The Bending Cross, a biography of the railroad union leader Eugene Debs:

A Federal commission later estimated that Pullman slashed wage rates 25 per cent between 1893 and May, 1894. The Rev. William H. Carwardine, a minister in Pullman who later wrote a book about the labor dispute there, believed that the reductions were even greater: “The average cut in wages was 33 ⅓ per cent; in some cases it was as much as 40 percent, and in many was fifty per cent.” ...

Mr. Carwardine added that an awareness of George M. Pullman, not an awareness of God, ruled the community: “An unpleasant feature of the town is that you are made to feel at every turn the presence of the corporation … This is a corporation-made and a corporation-governed town.”

Just two years into his ministry in Pullman, Carwardine found himself in the dual role of dissident prophet and labor journalist. He looked at pay stubs and did the math. He spoke to the members of his church about the material conditions of their lives. He had chosen the difficult path, unlike his counterparts in other local churches.

Rev. Carwardine’s congregation, consisting of Pullman’s laborers, was meeting in a room in the town’s Arcade. Down the street in the grand Gothic Revival church, Rev. E. Christian Oggel gave an impassioned sermon against collective worker action in 1894: “I deplore the strike in our midst last week because there is a maxim that half a loaf is better than no bread, and in my judgment the employees were getting two-thirds of a loaf.”

Somebody had to speak plainly about the conditions in Pullman, and the local press could not be counted on. Col. Duane Doty, editor of the Pullman Journal, was also employed by the Pullman Company as its historian and statistician. He made no effort to conceal his loyalty, and he regularly gave salesmanlike tours of the town to George Pullman’s friends.

The week after Oggel delivered his sermon, Carwardine gave his own sermon supporting the strike, which was quickly republished in newspapers across the region. Carwardine wrote in his 1894 book The Pullman Strike:

No one has deplored this strike more than myself. I wish that it might have been averted. But so long as the employees saw fit to take action I believe that it is the duty of all concerned to look the issue squarely in the face, without equivocation or evasion, consider the matter in its true light, and endeavor to bring about a settlement of the difficulty as speedily as possible …

Sometimes we preachers are told to mind our own business and “preach the gospel.” All right; I have preached the gospel of Christ, and souls have been redeemed to a better life under the preaching of that gospel. I contend now that in the discussing of this theme I am preaching the gospel of applied Christianity … The relation existing between a man’s body and his soul are such that you can make very little headway appealing to the soul of a thoroughly live and healthy man if he be starving for food.

When unjust systems are grinding people into the dirt, there is no middle ground for the church. Staying “neutral,” dealing only in the “spiritual,” is the same as siding with the oppressor. Imagine Moses watching his people enslaved in Egypt, forced to make bricks without straw, and contenting himself with home devotionals. Imagine Dietrich Bonhoeffer, fully aware of the rise of Nazism in his country, giving little sermons on personal piety. Imagine preachers in the United States giving sermons for 40 years without once challenging the doctrine of white supremacy.

When he gave his sermon, Carwardine was speaking first to his congregation and then to the greater community. He knew his words would reach George Pullman’s ears, too. When he wrote his book, he hoped to persuade the general public about the justice of the workers’ cause while counteracting the propaganda of the Pullman company machine.

What made these intelligent employees at Pullman strike? Were they rash and inconsiderate, or were they driven to their course by certain conditions over which they had no control, and which justified them in their action?

These and a hundred other questions are coming to me by mail from all parts of our country. Ten days after the employees struck, I delivered a sermon from my pulpit, which created profound interest in Pullman and Chicago, and which has since been copied broadcast in newspapers all over the United States. Owing to this fact, I am accosted on all sides for information concerning the true condition of things in this model town.

Carwardine was expressing a similar concern to the one Bonhoeffer, the anti-Nazi dissident, later expressed in some of his final writings. At the time of his execution in 1945, Bonhoeffer was working on a book called Ethics, which included a short essay titled “What is Meant by ‘Telling the Truth’?”

Bonhoeffer, like Carwardine, was cognizant of the weight his words carried in different spheres of influence. He wrote:

The truthfulness which we owe to God must assume a concrete form in the world. Our speech must be truthful, not in principle but concretely. A truthfulness which is not concrete is not truthful before God …

The real is to be expressed in words. That is what constitutes truthful speech. And this inevitably raises the question of the “how?” of these words. It is a question of knowing the right word on each occasion. Finding this word is a matter of long, earnest and ever more advanced effort on the basis of experience and knowledge of the real.

From the Smithfield pork plants of South Dakota to the Apple company towns of Shenzhen, there is still a need for truth telling. Like Carwardine and Bonhoeffer, may we tell it well.

***

Ray Ginger’s The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene V. Debs is available for $20 via Bookshop. Carwardine’s The Pullman Strike is available as a free PDF via the University of Minnesota.

The images used in this issue are as follows:

Interior view of the drawing room of Mrs. George M. Pullman's residence in Chicago with a small group of people gathered at one end. American Memory Collections, Library of Congress ID ichicdn.n073772.

The Rev. Mr. Carwardine. "He Spoke of Pullman," Chicago Times, June 16, 1894, Pullman Company Archives, 12/00/03, strike scrapbooks. vol. 1: 120-121. Pullman Company Archives.

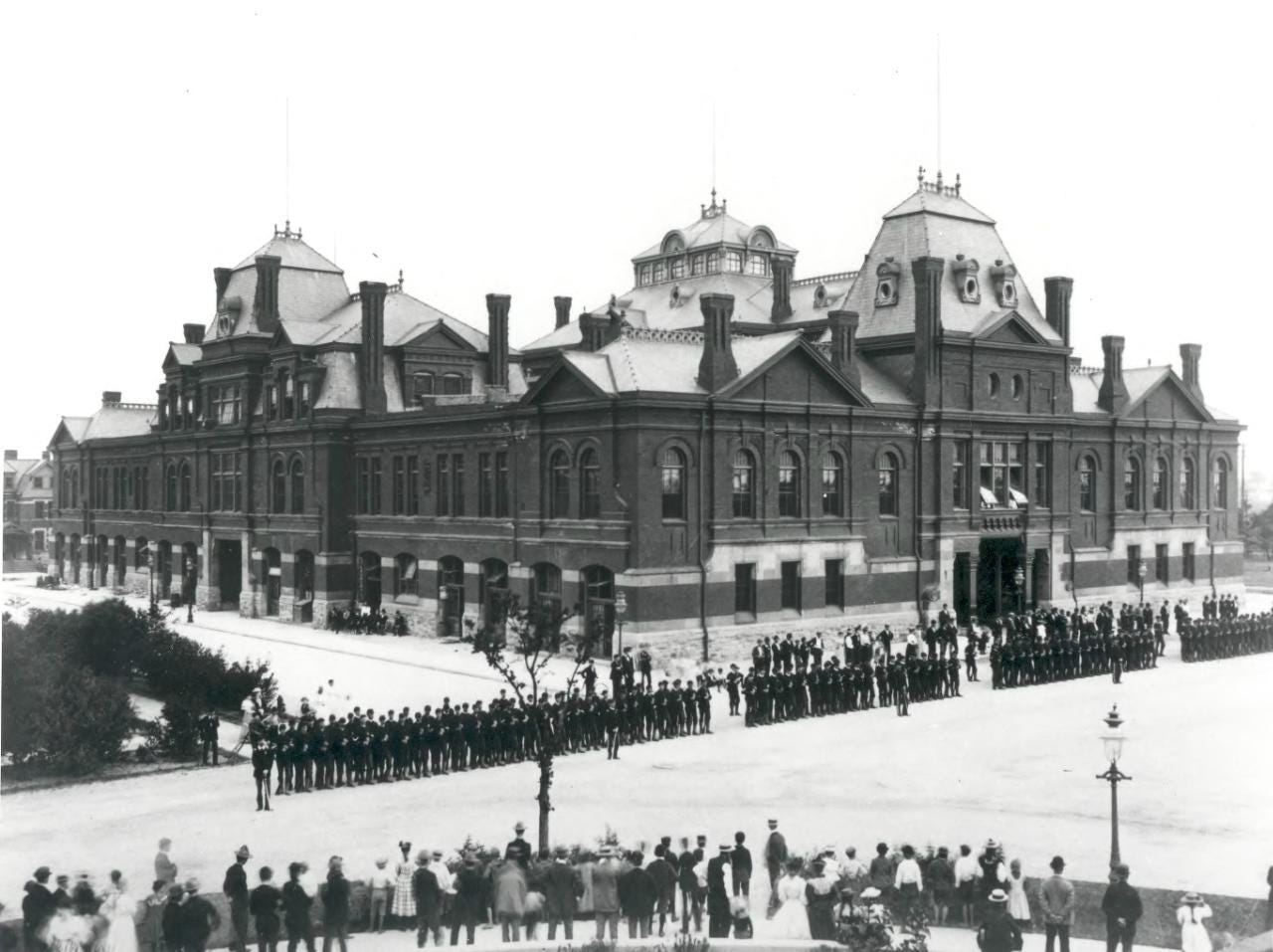

Pullman strikers outside Arcade Building in Pullman, Chicago. The Illinois National Guard can be seen guarding the building during the Pullman Railroad Strike in 1894. Abraham Lincoln Historical Digitization Project.