The pseudoscience of killing

There's 'no scientific or medical justification' for the way South Carolina executes people

For the time being, the state of South Carolina will not be allowed to kill inmates by running electrical current through their bodies or shooting them in the chest with rifle rounds.

“According to expert testimony, there is no scientific or medical justification for the way South Carolina carries out judicial electrocutions,” Fifth Circuit Judge Jocelyn Newman wrote on Sept. 6 in an order halting the executions of Freddie Eugene Owens, Brad Keith Sigmon, Gary Dubose Terry, and Richard Bernard Moore.

As for the firing squad, she wrote, “This constitutes torture, a possibly lingering death, and pain beyond what is necessary for the mere extinguishment of death.”

Unable to obtain lethal-injection drugs, the governor signed a law in 2021 requiring the state’s victims to choose between a 110-year-old electric chair or a newly formed all-volunteer firing squad. Judge Newman’s order, which draws on testimony from a 4-day trial in August, exposes how much of the state’s killing protocol is based on conjecture, tradition, and amateur research.

If and when the state kills a person by firing squad, a state employee will strap him to a metal chair in the death chamber at Broad River Correctional Institution in Columbia. A physician will place an “aiming point” somewhere over his heart, and someone will cover his head with a hood. A 3-member volunteer firing squad will stand 15 feet away and shoot him in the chest with rifles containing .308 Winchester 110-grain Tactical Application Police Urban ammunition. Unlike in traditional firing squads, no one gets a “conscience round,” a randomly assigned blank round that gives a shooter plausible deniability.

The rifle rounds will crack the bones in the inmate’s chest and create gaping wounds as they fragment inside his body. A slanted trough beneath the chair will collect the inmate’s blood, and black fabric draped on the walls will obscure the spray of fluid and bodily tissues.

If the inmate survives the first volley for 10 minutes, the firing squad will hit him with a second volley. Failing that, they can fire a third volley.

Colie Rushton, the S.C. Department of Corrections’ Director of Security and Emergency Operations, was called as a witness at the trial in August because he wrote the protocol for the firing squad. Here’s how Judge Newman described the rigor of Rushton’s research process:

He testified that he did internet research about historical uses of firing squads and the FBI’s testing of certain ammunition. Rushton spoke to officials in the State of Utah regarding their use of a firing squad, and he was the person who ultimately chose the ammunition to be used in such executions. However, Rushton admitted that the protocol was developed without consulting with any doctors, firearms experts, ballistics experts, or any professional who could determine the proper positioning of the target on the inmate’s body.

As for the electrocution protocols, Rushton testified that those were written before he started in his role in 2007.

“[W]hile he is knowledgeable about the electric chair itself and the voltage and timing applied pursuant to the protocols, he does not know why any specific voltage or time period was chosen,” Judge Newman wrote.

When designing death machines or assessing their cruelty, states face the perennial problem of finding subject matter experts. The problem is, there are none.

So instead, the states will call in technicians and academics to give their best guesses. In this case, the state of South Carolina called on a Dr. Ronald Wright, a forensic pathologist, who asserted that people subject to high-voltage electrocution immediately lose consciousness due to a phenomenon he called “immediate poration.” Judge Newman was unconvinced:

Dr. Wright could not, however, offer any affirmative proof to support this theory of instant poration and insensibility. To the contrary, Dr. Wright acknowledged that a person whose brain has been subject to instant poration would not be capable of breathing, moving, or screaming; and he was unable to explain electrocutions during which inmates breathed, moved, and screamed after the application of electric current.

In the absence of clinical trials for death machines, we are left with educated guesswork from experts in adjacent fields: doctors guessing at how to take a life rather than save it, forensic scientists guessing at what a victim felt rather than how they died, and so on.

With rare exceptions such as POW interrogators and the doctors in Nazi concentration camps, humankind has produced no actual experts in the inflicting of pain or the efficient extermination of human beings. It is worth noting that the single most influential figure in shaping U.S. execution policy and technology in the late 20th century also dabbled in the use of forensics to deny basic facts about the Holocaust.

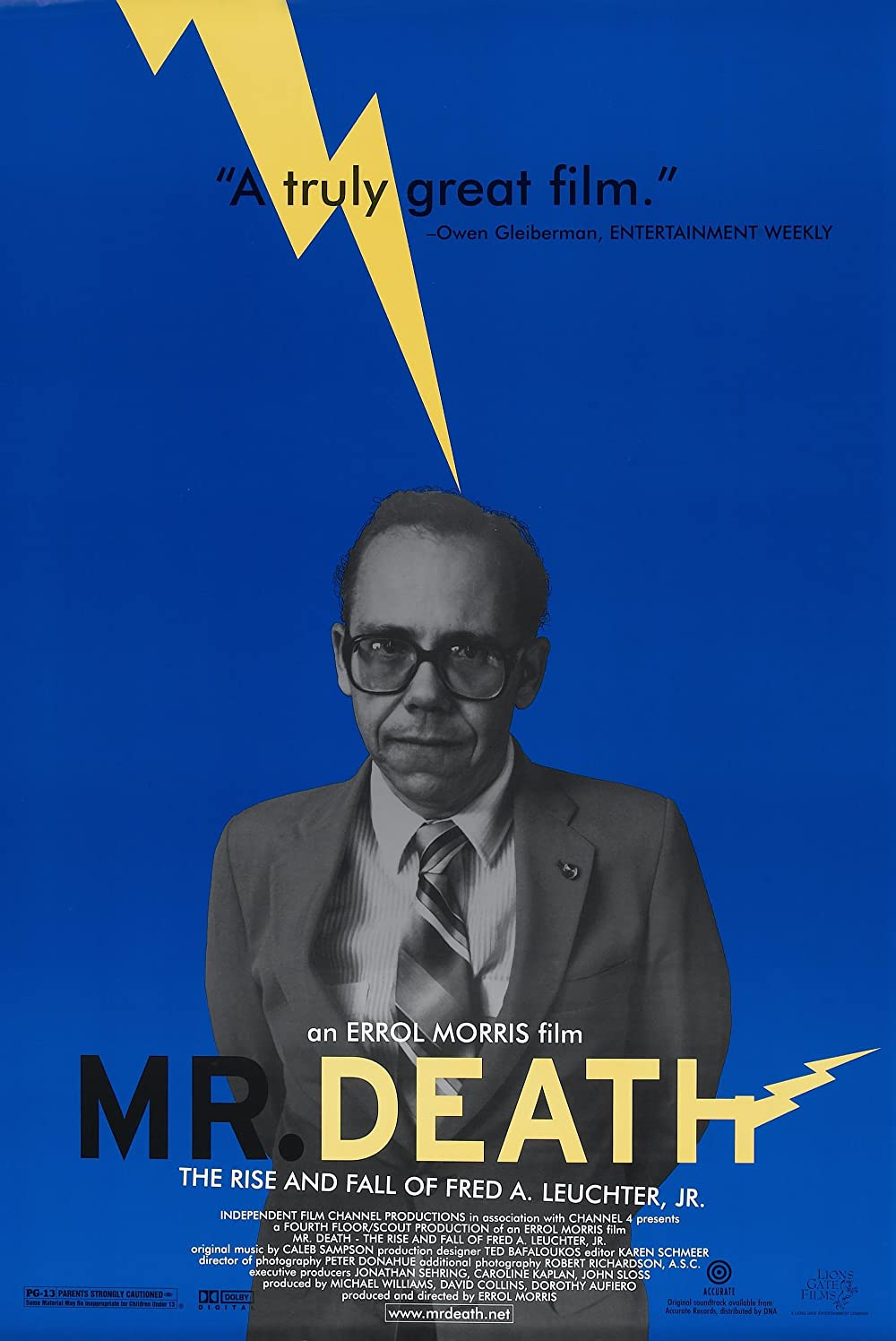

His name is Fred A. Leuchter Jr. of Malden, Massachusetts, and he is a self-taught electrician whose only credential is a bachelor’s degree in history from the University of Boston. Leuchter, nicknamed “Mr. Death,” provided death-penalty consulting and/or his own handmade execution equipment to at least 27 states between 1979 and 1990. 1 His company Fred A. Leuchter Associates, Inc., provided “Electrocution Technician” certificates for anyone who paid to take Leuchter’s training course.

Leuchter is no longer sought after as a public expert on the death penalty. His fall from favor has as much to do with his lack of actual expertise as it does with his well-publicized attempts to deny the scope and scale of the Holocaust by scraping samples off of bricks at a reconstructed gas chamber. The Leuchter Report was rejected as bunk by scientists and historians. In the 1988 trial of the neo-Nazi Ernst Zündel for distributing Holocaust denial material, a Canadian judge dismissed Leuchter’s testimony as being of "no greater value than that of an ordinary tourist."

I spoke to Fred Leuchter on the phone last year at his home in Malden. He claimed that he continued to get calls from prison officials even after he was publicly discredited because they had no one else to ask questions about the mechanics of killing.

“Wardens would turn around and say, ‘We don’t know anything about Fred Leuchter, we haven’t dealt with him,’ and then two hours later they call me up on the telephone and say, ‘Hey, we’ve got an execution scheduled and I’m having a problem with the equipment, what do I do?’” Leuchter said.

Whether or not he still gets those calls, some of his homemade execution equipment is probably still in use. He sold an electrocution helmet to the state of South Carolina for $800 in 1983, according to the Greenville News. 2 No new company or inventor has risen to take his place as the premier manufacturer of electrocution equipment in the United States.

I asked the S.C. Department of Corrections last June if it still had Leuchter’s helmet in the death chamber. Director of Communications Chrysti Shain wrote back, “The department doesn’t have any records about this, and even if it did, the records would be restricted and not considered public under FOIA.”

***

A shocking amount of junk science and fuzzy marketing language have gone into the modern practice of capital punishment. Slogans like “quick and painless,” proffered up by politicians and entrepreneurs to soothe the public conscience, were always wishful thinking at best.

When the governor of New York proposed that the state find “a less barbarous manner” than hanging for carrying out its executions in 1885, he set up a commission to investigate the matter. It consisted of two attorneys and a dentist.

This three-man brain trust got to work reviewing the 34 known methods of capital punishment 3 and prepared a report for the state legislature. They narrowed the list down to just 4 that they deemed worthy of serious consideration — guillotine, garrote, firing squad, or gallows — but threw those out because they were either too cruel, too likely to mutilate, or too closely associated with the French Revolution. So they had to come up with something new.

The dentist on the governor’s commission, Alfred P. Southwick of Buffalo, already had a new method picked out:

In 1881 Alfred Southwick had observed the quick, seemingly painless death of a Buffalo man who had contacted the brushes of an electric generator. Reasoning that electricity would be quicker, surer, and less painful than hanging, Southwick had carried out some crude experiments on electrocuting animals and had begun to advocate consideration of legal electrocution even before his appointment to the commission. 4

Seeking support for his position, Southwick wrote a letter seeking input from another expert: an inventor with something to sell.

When Southwick wrote to Thomas Edison seeking backup, Edison initially turned him down, saying he opposed capital punishment. Edison eventually relented after Southwick convinced him that he would be helping to find a more humane method for a practice that would continue no matter what.

Edison may have had other motives, too. By the mid-1880s he was locked in a bitter public fight with a rival, George Westinghouse, over the best method for transmitting electrical current to consumers. Edison favored low-voltage direct current, which he considered safer. Westinghouse, meanwhile, was pushing for alternating current, which could transmit over longer distances with voltage stepped up or stepped down according to consumer needs. Edison told anyone who would listen that AC was deadly.

Edison wrote back to Southwick in 1887:

The best appliance in this connection is, to my mind, the one which will perform its work in the shortest space of time, and inflict the least amount of suffering upon its victim. This, I believe, can be accomplished by the use of electricity, and the most suitable apparatus for the purpose is that class of dynamoelectric machinery which employs intermittent currents. The most effective of these are known as “alternating machines,” manufactured principally in this country by Geo. Westinghouse . . . The passage of the current from these machines through the human body even by the slightest contacts, produces instantaneous death. 5 (emphasis mine)

Edison’s letter won over the chairman of the committee. The committee passed its recommendation along to the legislature, which passed a bill requiring capital punishment by electrocution in 1888. Harold P. Brown, a self-trained electrician, established himself as an expert by carrying out electrocution experiments on dogs and subsequently won state contracts to install the first electric chairs in three state prisons.

The first man the state of New York killed by electrocution was William Kemmler, a mentally disabled man who had been convicted of murdering his girlfriend with a hatchet. On Aug. 6, 1890, he wished his executioners luck and sat in the world’s first electric chair. The state ran 1,000 volts of alternating current through his body for 17 seconds without killing him, then upped the voltage to 2,000. It took 8 minutes in all to kill him, during which time he kept breathing as the smell of his cooking flesh filled the room. Two witnesses were nauseated.

“An awful spectacle, far worse than hanging,” one reporter wrote.

“They could have done a better job with an ax,” Westinghouse quipped.

Edison helpfully suggested that the state try placing the inmate’s hands in jars of water next time.

***

Kemmler’s execution in 1890 started at 1,000 volts before ramping up to 2,000. Today South Carolina’s protocol starts by running 2,000 volts through a prisoner’s body for 4.5 seconds before ramping down to 1,000 volts for 8 seconds, then 120 volts for 2 minutes.

We don’t have a good rationale for either method, just a series of suppositions.

Capital punishment is still done by trial and error, with a lot of error. The Death Penalty Information Center estimates that 3% of executions between 1890 and 2010 were botched.

Questions of voltage aside, the basic layout of the electric chair – which runs current from an electrode on the head to another on the leg – is not even permitted for animal slaughter, Dr. John Peter Wikswo of Vanderbilt University testified in August. The human skull is a bad conductor, so the current passes through muscles all over the body, causing constrictions strong enough to break bones.

One expert witness in the trial, forensic pathologist Dr. Jonathan Arden, reviewed autopsies and found at least one in South Carolina that was botched because an electrode fell onto the inmate’s eyes. He testified that inmates’ internal organs received burns equivalent to cooking and that they were likely conscious as it happened.

The testimony in August focused on the physical pain felt by the state’s victims in the seconds or minutes after lethal means are applied. No one spoke about the pain that precedes the jolt or the gunfire. The Christian nationalists who control South Carolina’s government are well acquainted with that pain, at least in a metaphorical sense: The gospel writer Luke, a physician, tells us that on the eve of his execution, Jesus prayed in agony and sweated blood in the Garden of Gethsemane.

The plaintiffs in this case have all been on death row for 20 or more years. Men in similar conditions have been driven to “death row syndrome,” a set of symptoms that can include suicidality and psychotic delusions.

The pain of the waiting falls outside the scope of this case, for now. The state will almost certainly appeal Judge Newman’s order. The governor will make his little speeches, and a small crowd will cheer for the punishment of men the world practically forgot. The suffering will continue until death or mercy wins.

***

Brutal South is free. If you would like to support my work and get access to the complete archives with subscriber-only content, paid subscriptions are $5 a month.

Bookshop // Twitter // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts

Deborah W. Denno, Is Electrocution an Unconstitutional Method of Execution? The Engineering of Death over the Century, 35 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 551 (1994), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol35/iss2/4

Fox, William. “Electric chair designed to be most humane, official says.” The Greenville News, September 5, 1991, p. 10A. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/79628394/fred-a-leuchter-greenville-news-part/

Denno, footnote 87: “The Report began by examining a list of offenses that carried the punishment of death in the Bible and in Athens. See COMISSION REPORT, supra note 84, at 4-5. The Report then discussed the evolution of death penalty law in England and the United States, id. at 6-13, and ended with a review of all 34 methods of capital punishment known at the time of the Report. These were: auto da fe (public burnings that took place during the Spanish Inquisition), id. at 14, beating with clubs, id., beheading, id. at 14-19, blowing from a cannon, id. at 19, boiling, id. at 19-20, breaking on the wheel, id. at 20, burning, id. at 21-22, burying alive, id. at 22, crucifixion, id. at 22-25, decimation (executing every tenth offender but not informing the other condemned persons if they were to be put to death until the fatal shot was fired), id. at 25-26, dichotomy (bisecting), id. at 26, dismemberment, id. at 26-27, drowning, id. at 27-28, exposure to wild beasts, id. at 28, flaying alive (skinning alive), id. at 29, flogging or knout, id. at 29-30, garrote (placing a cord about the offender's neck and twisting it with a stick until strangulation is achieved), id. at 30, guillotine, id. at 30-33, hanging, id. at 33-38, hari kari, id. at 38, impalement, id. at 38-39, iron maiden (involving a statue of the Virgin Mary from which knives sprang forth), id. at 39, peine fore et dure (placing a heavy weight on the chest to restrict breathing), id. at 39-40, poisoning, id. at 40, pounding in mortar, id., precipitation (throwing from a high point), id., pressing to death, id. at 40-41, rack, id. at 41, running the gauntlet (forcing the condemned to run between rows of soldiers who each deliver blows), id. at 41-42, shooting, id. at 42-44, stabbing, id. at 44, stoning, id. at 44-45, strangling, id. at 45-47, and suffocation, id. at 47.”

Terry S. Reynolds & Theodore Bernstein, Edison and “The Chair,” 8 IEEE Tech. & Society Magazine 19, 19 (1989). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=17683

Reynolds, 21