The conscience round

The state of South Carolina is hell bent on killing people again

In a traditional firing squad, each shooter receives a rifle loaded with either live ammunition or a blank known as a “conscience round.”

In theory, the existence of the conscience round allows each shooter to fire straight, believing that they might not be individually responsible for taking a person’s life.

Skilled shooters know what has happened as soon as they pull the trigger, of course. They can feel the difference between the recoil of a live round and the impotent bang of a blank.

The South Carolina Senate passed a bill on March 3 that would allow the state to use firing squads as a method of execution. The same bill would also bring back electrocution as the default method, allowing capital punishment to resume 8 years after the state's last doses of lethal injection drugs expired. The bill awaits debate in the House.

I abhor the death penalty on religious, philosophical, and legal grounds. It is cruel, it is arbitrary, it is expensive, and it is not a crime deterrent.

The death penalty is a tool of systematic racism. Here in South Carolina, we know that Black people make up 27% of the state’s population but more than half of its death row. Across the country, state-level studies have consistently shown that prosecutors, juries, and judges disproportionately wield the death penalty against Black defendants and against defendants who have murdered white victims.

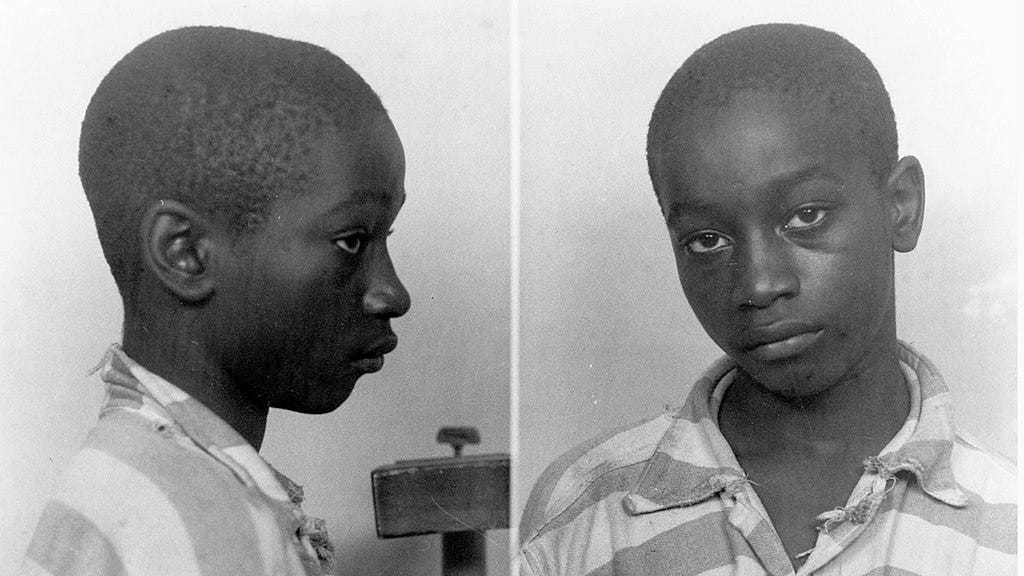

We have a long history of botched trials and false convictions. The state of South Carolina executed a 14-year-old boy named George Stinney in 1944 using an electric chair with a Bible as a booster seat; a court overturned his murder conviction 70 years later. We know that even the federal government will execute mentally disabled people like Corey Johnson, who died by lethal injection this January.

I know that most of the people killed by public execution are not sympathetic figures like Stinney and Johnson. I understand the instinctive belief that the ultimate crimes deserve the ultimate punishment, even though I reject that belief. But as my state prepares another legal maneuver to resume the killing of condemned men, I think it's best to take full stock of our moral landscape.

This isn’t the first time South Carolina politicians have debated the morality of firing squads in my lifetime. When South Carolina Rep. Joshua A. Putnam (R-Anderson) introduced a bill to create firing squads in 2015, he stipulated that some members of the firing squad would shoot blanks, following the old “conscience round” custom.

“What would happen is it would be five people, trained marksmen, the best and most precise marksmen within the state we have,” Putnam told me when I interviewed him for the Charleston City Paper at the time. “Four of their rifles would have blanks in them; only one rifle would have a live round.”

Putnam wanted to bracket off the morality of capital punishment and focus on the method. The law called for killing, the state had a list of 44 people to kill, and he was proposing a practical way to do it.

“I’m trying to, No. 1, find a solution to the problem the state faces right now, and also find a more humane way of doing it,” he said.

The measurement of humaneness in capital punishment is arcane and subjective. Proponents of the firing squad might point you to a 1938 experiment conducted by a Dr. Stephen Beasley of Utah, who monitored the heart rate of prisoner John Deering and found that his heart stopped beating within 15 seconds after a firing squad shot him in the chest. This, some would argue, is relatively quick.

Macabre experiments notwithstanding, we can ascertain that execution causes suffering — first psychological anguish and then, in most cases, physical pain. One literature review by Dr. Harold Hillman (Perception, 1993) found that nearly every method of capital punishment from stoning to decapitation to electrocution caused physical pain.

“The general view has been that most of the methods used are virtually painless, and lead to rapid dignified death,” Hillman wrote. “Evidence is presented which shows that, with the possible exception of intravenous injection, this view is almost certainly wrong.”

***

The state of South Carolina is keen to kill again. There hasn’t been an execution here since 2011.

State leaders who want to resume executions find themselves in a predicament. Drug manufacturers have cut off South Carolina’s supply of the drug cocktail used in lethal injections, hewing to the notion that their products should be used to preserve life and not end it. Our last dose expired in 2013.

The death chamber at the Broad River Capital Punishment Facility still contains a wooden chair for electrocution, which technically remains an option. But under current law, the condemned person must choose the electric chair, which no one has done since 2008. So our state’s top legal minds have set to work looking for loopholes.

In April 2015, Rep. Putnam proposed the firing squad as an option. The bill stalled out in committee.

Desperate to kill a 52-year-old man in the winter of 2017, South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster proposed a “shield law” that would keep a drug manufacturer’s identity secret if it sold lethal injection components to the state. Other states had passed similar laws at the time, leading to the creation of experimental drug cocktails that killed their victims slowly and with great anguish. Shield bills were introduced in the South Carolina House and Senate, but they didn’t pass.

In 2018, a Christian CrossFit entrepreneur named William Timmons proposed executing everyone on death row by electric chair whether they opted for it or not. The bill he co-sponsored passed the state Senate but stalled in the House. Timmons now serves in Congress.

This year, South Carolina lawmakers wrote a bill (S. 200) that would require the electric chair like in Timmons’ 2018 bill, but with the added option of a firing squad option like in Putnam’s 2015 bill. It passed the Senate on March 3 with bipartisan support and is currently in the House Committee on Judiciary.

The firing squad option was tacked onto the bill by two former prosecutors, a Democrat and a Republican. Sen. Dick Harpootlian, the Democrat, noted that his state was not likely to abolish the death penalty anytime soon like Virginia did in February.

“The death penalty is going to stay the law here for a while. If it is going to remain, it ought to be humane,” Harpootlian said, echoing Rep. Putnam’s moral retreat.

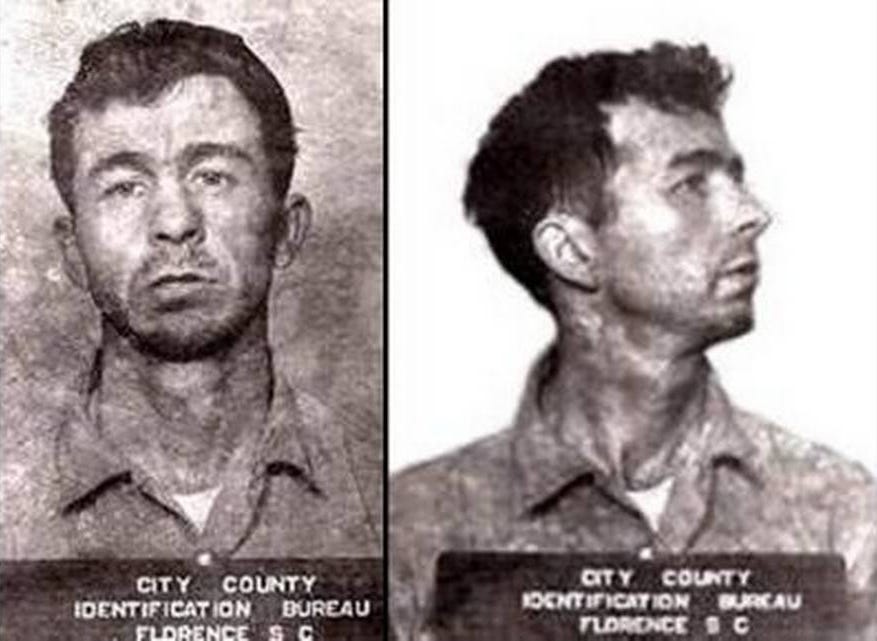

Harpootlian sounds a note of resigned pragmatism now, but he publicly celebrated the killing of Donald Henry “Pee Wee” Gaskins Jr., whom he helped send to the electric chair while serving as a deputy solicitor in 1991.

“The only time we can relax our vigilance on Pee Wee is when he is in hell,″ the eminently quotable Harpootlian said at the time, according to the Associated Press.

Raised in an environment of extreme neglect and abuse, Gaskins grew up to become a serial killer, a rapist, and an avowed racist who claimed responsibility for between 100 and 110 murders.

In the eyes of Harpootlian and the general public, Gaskins was remorseless and unreformable, a poster child for the electric chair (lethal injections did not begin in South Carolina until 1995). Even under the constraints of death row, he was keen to kill again, and he found a way: He murdered a fellow inmate with an improvised explosive device disguised to look like a radio.

In an interview that did not prick many consciences at the time, Gaskins pointed his finger back at the state that was about to kill him. He called electrocution ″one of the most malicious, most cold bloodest, premeditatest murders that there is. It can’t be no worse than if I was to sit down and plan to kill somebody.″

Between 1912 and 2011, the state of South Carolina killed a few more people than Gaskins did, and was maybe a little less clever. Since taking over the duties of execution from the counties, which tended to use hanging and lynch mobs, the state executed 282 people either by electric chair or injection.

***

Debating the methodology of capital punishment is a lot like passing around rifles loaded with conscience rounds. Lawmakers and voters can tell themselves they did their best given the circumstances, and that perhaps they are not complicit in the act of killing.

The veil of conscientiousness won’t save us from guilt, though. In a state that kills its own people, we are all the shooter with the live round. We are all the round itself, piercing another man’s flesh and stopping his heart. We are all soaked in his blood.

I like to imagine what would happen if my state’s politicians set their minds to human flourishing with the same doggedness and ingenuity they apply to enforcing the death penalty. But their priority is death, and so we get new and innovative approaches to killing.

On a daily basis, South Carolina’s elected officials kill by neglect: They strangle rural healthcare systems via austerity; they allow highways to crumble until they are lethal to drive on; and they swear off public health advice during a raging pandemic, leaving thousands of vulnerable and elderly people dead in their wake.

But there are times when mere neglect is not enough in the eyes of the state. There comes a time to kill, and the state will do it in our name.

***

Brutal South is a free weekly newsletter and podcast. To get access to subscriber-only issues and episodes for $5 a month, click Subscribe now and choose the Monthly or Annual option.

Twitter // Bookshop // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts

A Pew Research Center survey found that in September of 2016 support for death penalty was the lowest in more than four decades. By June 2018 support for the death penalty had increased. Wonder what could have happened during that time that would have hardened the hearts of people?? Interesting that legislators in South Carolina don't discuss that the death penalty is orders-of-magnitude more expensive than imprisonment.