State tax policy is class warfare

Your county council steals from children and gives the money to megacorporations

You can tell your local government is about to hand a bag of money to some capitalists when it starts using code names.

On April 27, 2021, Lexington County Council put something called “Project Bronco” on its agenda and voted unanimously to approve it. The public found out after the fact that “Project Bronco” was a sweetheart tax deal for JJE Capital Holdings, the private equity firm behind Palmetto State Armory, a gun manufacturer and chain of gun stores. The company planned to open a small-arms factory inside a former brake plant in West Columbia — but first they wanted local taxpayers to sweeten the deal.

The Post and Courier’s Jessica Holdman reported:

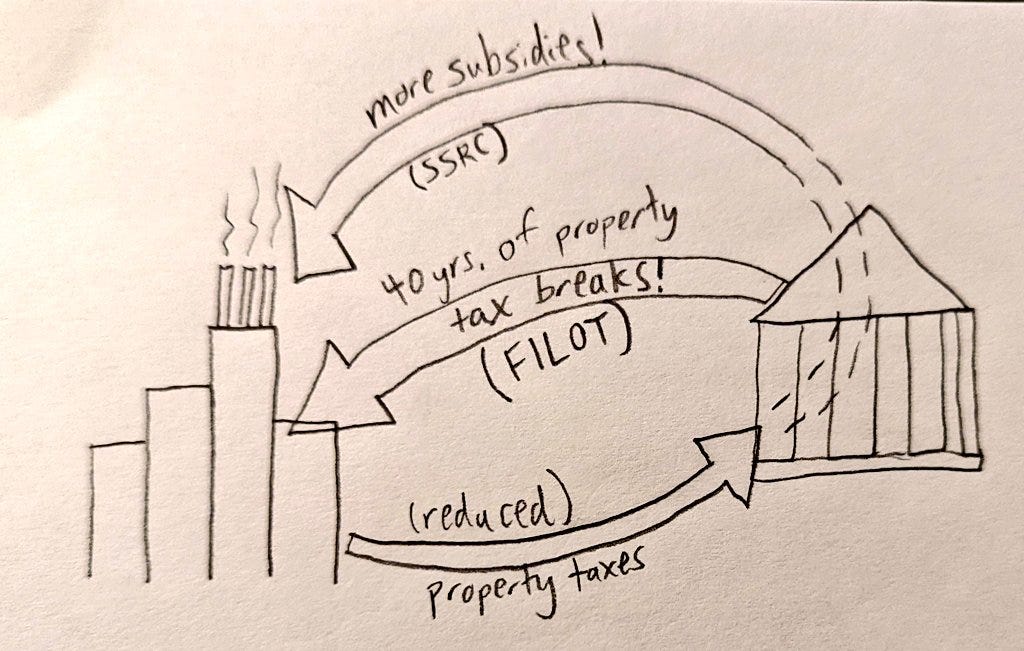

Under the agreement, Palmetto State Armory will receive a reduced property tax rate of 6 percent rather than the typical 10 percent corporate rate charged to South Carolina manufacturers, for the next 20 years.

The company is also asking for tax credits to further buy down its property tax bill — equivalent to 20 percent of the investments it makes for the first five years and 10 percent for the five years after.

No one was able to give an estimate of how much tax revenue Lexington County was forfeiting in the deal. In exchange, Palmetto State Armory promised to hire 150 additional employees. I have not seen any indication that the county can or will enforce that promise, or even that the hires would have to be local.

I live in a state that has let capitalists run roughshod over its people for nearly its entire history. Reading about these sorts of secretive deals drives me absolutely bonkers. Somehow it’s become de rigueur for local governments to lavish corporations with bribes and inducements for the honor of hosting their enterprises, maintaining the roads to their front doors, breathing the air pollution they generate, and putting up with the working conditions they dictate.

It is not at all clear what the public is getting out of these deals, but we have a pretty good idea of what we’re losing. Because of the way our state legislature has structured the tax code, public schools are the biggest losers in these types of deals.

This is class war, plain and vulgar. We rob our public schools to fork more money over to corporations. Poor people, rural school districts, and communities of color are the ones who pay the heaviest price.

In May, the watchdog group Good Jobs First published a report that attempted to calculate how much money South Carolinians are giving away in the form of corporate tax abatements. In the Fiscal Year 2021 alone, South Carolina public schools reported losing $534 million in revenues, a figure that rises every year. In the 5 years since new accounting standards required local governments to report these losses, South Carolina schools have lost out on a total of $2.2 billion. No other state reported losing more school revenue to private companies.

From the report:

County governments in South Carolina exercise—seemingly without restraint—their state-granted authority to give businesses multi-decade tax exemptions and credits, giving up the revenues that schools need and compounding the state’s already-severe K-12 funding crisis. Not only are 90% of the districts underfunded, but the poorest districts also suffer disproportionately from revenue deficiencies. Despite bearing the brunt of the costs, South Carolina school districts have no power in the award process.

In practical terms, this tax policy means that our teachers make less money than the regional average, classroom sizes have ballooned, and the physical state of many of our rural schools is downright dangerous. South Carolina Education Association President Sherry East broke it down in simple terms at a May 17 video conference (I was invited to participate in the call but had to miss it due to a scheduling conflict):

I got calls last summer from teachers that were working in buildings with no air conditioning. They couldn’t take their lunch to school and sit it on the table because they were afraid it would spoil. During COVID we were told to keep your windows open, let fresh air get in — we heard from lots of educators that the windows don’t open and close … You look at the money that’s lost in this report and think, how many things could this fix? how many buildings could this repair? and how many teacher salaries and support staff could be hired with the money that we are handing to profitable organizations?

South Carolina’s state and local governing bodies are not unique in letting capitalists play shell games with public funds. 1 We may have even been late to the game; our state didn’t enable local governments to pass Fee In Lieu of Taxes (FILOT) deals until 1988.

(If you want to look up what data are available for your state, check out the Good Jobs First Subsidy Tracker and Tax Break Tracker, which are incomplete but pretty good starting places for research.)

Still, this is my state and my kids who are missing out on a fully funded education so that some boardroom dandy can buy a second lake house. So, just like I did when the last Good Jobs First report came out in 2020, I’ve been stewing on these numbers.

The latest report spent some time dwelling on Berkeley County School District, which serves 36,000 students in the inland Charleston suburbs and reported losing $83.9 million in Fiscal Year 2021. That amount was higher than any other South Carolina school district, and it came third in the country only behind Philadelphia City Schools in Pennsylvania and Hillsboro School District in Oregon.

One weakness of current accounting standards is that government bodies only have to report total revenues lost; they don’t have to provide an itemized breakdown of the tax abatements they handed out.

But we know at least one of the offenders in Berkeley County: Google.

In 2006, a Google subsidiary called Pyrite, LLC, applied for subsidies from Berkeley County government and got them under a veil of secrecy and nondisclosure agreements. (At some point Pyrite changed its name, inexplicably, to “Maguro Enterprises.”)

In 2007, Google announced it would open a massive data center at the Mt. Holly Commerce Park near Moncks Corner, and it has since expanded the facility to cover 500 acres. You can now get a job in the Goose Creek metropolitan area maintaining rows up on rows of hot server racks.

In addition to exploiting cheap non-union labor, Google is also taking our water: In 2016, in an effort to cool the air in its server farm, the company successfully applied to draw 1.5 million gallons of groundwater per day from an aquifer near Charleston. (If the story sounds familiar, I talked with my friend the professor James Gilmore about the environmental and agricultural impacts of this deal way back on Episode 5 of the podcast.)

Oh, and the county hurled bags of money at Google too. One of the most powerful corporations on earth got the white glove treatment: tax abatements via FILOT, cost reimbursement for infrastructure via a Special Source Revenue Credit, and extra benefits through the designation of a Multi-County Industrial Park. If that all sounds like gibberish, it’s because lawmakers came up with ways to give away public money and figured out the wording afterward.

We still don’t know exactly how much of Berkeley County Schools’ $83.9 million loss is going to Google. My former colleague Tom Novelly tried to pry out some details in a 2020 Post and Courier story:

[H]ow much water and electricity the tech giant uses, and details of tax breaks are hidden behind non-disclosure agreements and private business negotiations. Minimal information available to the public indicates sizable bargains for the organization, while leaving the taxpayer in the dark.

The land was sold to Maguro Enterprises LLC, the company created for the Google purchase, in 2007 for $17 million. But the assessed and appraised value of the massive campus is $0, according to public land tax records.

Minimal amounts of land taxes have been paid on that plot of land.

A Post and Courier review of 10 years worth of land tax information showed that Maguro Enterprises paid $275,946 on four parcels of land — or an average of about $28,000 a year. Some parcels of Google’s campus had a yearly tax payment as small as $10.

The county did not require a single job to be “created” in exchange for this deal.

The secrecy, the preposterous code names, the bending of tax codes to the will of the wealthiest few — these are not new phenomena, and they are not unique to South Carolina. Florida was ahead of its time in this respect, turning a blind eye while the Walt Disney Company bought up thousands of acres for Disney World in the 1960s via shell companies with cryptic names like Ayefour Corporation and Reedy Creek Ranch Corporation before bending state tax law and municipal codes to its will in the formation of a quasi-sovereign Reedy Creek Improvement District.

But today, as best we can tell from the available records, South Carolina politicians are masters in the art of the raw deal.

***

Brutal South is free, but you can support my work with a $5/month subscription that gets you access to subscriber-only stuff like these two pieces from last week:

Bookshop // Twitter // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts

Part of the reason South Carolina looks so bad in these reports is that its school districts are unusually good at complying with the relevant accounting paperwork, GASB Statement 77 on Tax Abatement Disclosures. This report became part of Generally Accepted Accounting Procedures for all US local governments in 2017, but followthrough has been spotty to say the least. For more information on GASB Statement 77 reporting and how to hold your local government accountable, see my newsletter from Sept. 23, 2020, “Tracking the elusive tax dodge.”