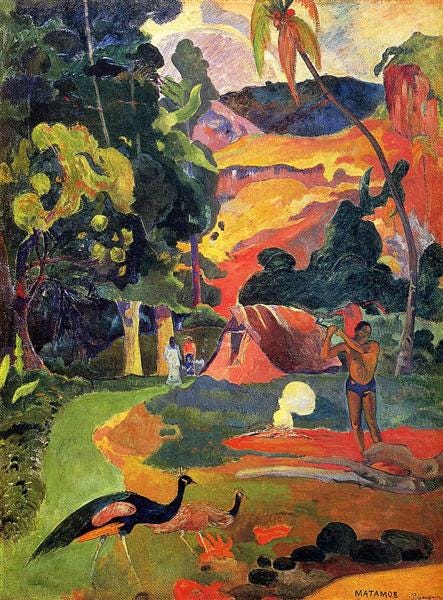

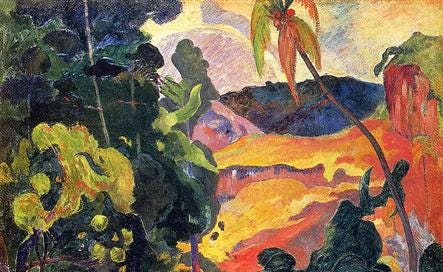

Gauguin, Paul. Landscape with peacocks. 1892.

We live in a world where states and municipalities have to strut like peacocks displaying their plumage to potential mates, fanning out radiant displays of legalized bribery to lure coy multi-billion-dollar multinational corporations into their roost.

We witnessed one high-profile version of this mating dance in 2018 when cities tripped over themselves wooing Amazon into their territory with lavish economic incentives. We saw it in 2014 when Apple used the sovereign republic of Ireland as a tax haven, paying just $50 in taxes for every $1 million the company earned in Europe.

The biggest deals grab the headlines, but local governments routinely do the same self-abasing mating dance on a smaller scale. These bassackward transactions often fly under the radar, but they add up.

My favorite example is Bass Pro Shops, a big-box outdoor retailer that routinely nets sweetheart deals to build new stores in cities across the United States. The government of Oklahoma City even spent $17.1 million of public funds to build a new store for Bass Pro Shops in 2003.

One of the only organizations I know of that systematically tracks this sort of corporate welfare is a policy think tank called Good Jobs First. According to the group’s Subsidy Tracker, Bass Pro and its former competitor Cabela’s, which it bought, have received more than $911 million worth of grants, loans, and tax credits from federal, state, and local governments since 1995. Your local bait and tackle shop didn’t see a dime of that tax relief, and public services in your community missed out on a lot of potential funding.

Good Jobs First released a fairly damning report this month on the ways corporate tax incentives have impoverished the public schools in South Carolina, the state where I live. It’s the first of several state-level reports they’ll be publishing, and it highlights a perfect storm of desperate poverty, pro-corporate government, and willful defunding of public education.

If you’re reading this newsletter in South Carolina, you might want to just read the whole report here, or read my takeaways in the next section. If you’re from elsewhere, keep scrolling; I’ve got a few things to say to you too.

What it means for South Carolina

When South Carolina sells its labor to the world, the pitch is that the workers are docile and the taxes are low. Because of this, tax incentives rarely raise the ire of any but the most consistent small-government Republicans (Mark Sanford, I tip my hat to you for once). They don’t get much scrutiny from corporate Democrats either.

South Carolina public school districts missed out on $423 million in Fiscal Year 2019 alone due to tax breaks granted to corporations by county governments, according to the report. That figure was up by $99 million from the last annual count in Fiscal Year 2017.

The report states:

The revenues of South Carolina’s school districts are reduced via programs that grant businesses tax abatements for extremely long periods of time—up to 40 years—which could effectively be permanent exemptions. Moreover, some of the largest per-student revenue losses are being reported by school districts with the highest student poverty; and deals with large corporations that entail hundreds of millions of dollars in tax abatements over multiple decades have been granted by counties that are already in economic distress.

As the report points out, local school boards don’t get to veto these tax breaks, even though their budgets are directly affected. County councils pass out tax breaks like candy because they’re eager to drum up business and lure “job creators,” and school officials have to figure out how to pay their teachers and educate the children of those companies’ employees with whatever’s left.

It’s usually impossible to tell whether these public investments in private businesses are paying off in local communities. County governments make their deals as opaque as possible, often dealing with shell subsidiary companies and cloaking the specifics of their tax deals behind broadly defined “trade secrets.” They often require no public reporting on the number of employees hired, what salaries they make, and whether the employees were hired locally.

Good Jobs First was able to get some top-level dollar figures from county governments thanks to a fairly new accounting rule (see the next section for more about that), but the specific incentives doled out to individual companies are often difficult to suss out. Local journalists have to dig up these details themselves.

My old colleague Tom Novelly at The Post and Courier tried to do just that earlier this year when he wrote about Google’s massive data center in Moncks Corner, S.C. Here’s an excerpt from his story, which was cited as a case study in the Good Jobs First report:

When the deal for the data center was announced in 2007, it was described by former Gov. Mark Sanford as a “real win for South Carolina” and the government offered $4 million in tax breaks if Google created 200 jobs.

But the company opted not to pursue that grant money that was based on creating 200 jobs. The tech giant turned to Berkeley County and they were welcomed with open arms. Berkeley County government didn’t include a job creation requirement.

Berkeley County benefits financially from Google, but how much water and electricity the tech giant uses, and details of tax breaks are hidden behind non-disclosure agreements and private business negotiations. Minimal information available to the public indicates sizable bargains for the organization, while leaving the taxpayer in the dark.

(As Tom noted in his article, Google also has a profound environmental impact, sucking up water from the local aquifer to cool its data center. Check out Episode 5 of the Brutal South Podcast for more about that.)

Corporate tax subsidies are just one piece of South Carolina’s austerity-strangled school funding system.

At the state level, the legislature under-funded its own education mandates by $497 million in the 2018-19 school year alone, an arrangement that disproportionately harms poor, rural, and majority-black districts. The Republican-controlled legislature has refused to address this fundamental inequity despite a 2014 State Supreme Court order and a 2019 teacher protest action that saw 10,000 people flooding the Statehouse lawn.

Short of a sustained teacher strike, it’s hard to say what will force a change. Public shaming doesn’t work on the shameless. Many teachers are taking a personal day off today, Sept. 23, to lobby their legislators, and I wholeheartedly support them. (I’ve mentioned this before, but follow SC for Ed on Facebook and Twitter if you want to stay up to date on teacher activism in this state.)

What it means for the rest of y’all

Let’s talk about how you can use government accounting rules to put corporate moochers on blast.

The basis of the Good Jobs First report is a new accounting rule that took effect in 2017, requiring government bodies to report their revenue losses due to economic development tax abatement programs. Prior to that rule, there was no nationwide reporting requirement on these sorts of handouts.

If you really want to dig into corporate subsidies in your state or county, start asking your elected officials about the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) Statement No. 77 on Tax Abatement Disclosures (it rolls off the tongue, I know). Here’s a quick explanation from the South Carolina report that you can pass along:

This obligation applies whether the government is the actively granting entity—such as … counties—or a second government that loses revenue passively, such as the state’s school districts.

It turns out South Carolina local governments are “exemplary” when it comes to filling out GASB Statement No. 77, according to the report. Other states, not so much. That, combined with the sharp uptick in South Carolina’s corporate tax breaks since 2017, prompted Good Jobs First to highlight South Carolina first in its new series of state profiles.

The report gives credit to the South Carolina Association of Counties for taking a proactive approach and “ensuring that local governments had the information needed to abide by the rule.” That sounds like dry accounting work, and it is. But it’s the sort of grunt work we’re going to need in order to blow the lid off of corporate handouts.

In my more optimistic moments I like to imagine living in a country where public servants don’t bow down in front of private companies and grovel for jobs on behalf of their constituents. I like to imagine bringing these corporations to heel, from Google all the way down to Bass Pro Shops.

I don’t know the path to get there. But I know it starts with exposing the bare basic facts.

***

If you enjoyed today’s newsletter, you might appreciate this one from last year about the myth of job creators.

In other news, I recently put in an order for 250 3-inch vinyl stickers with the Brutal South podcast logo on them, and I’ll be mailing them out to paying subscribers as soon as they arrive from the printer. If you’re a paying subscriber and you haven’t done it yet, just reply to this email and let me know your mailing address.

If you aren’t a paying subscriber, here’s the deal: $5 a month gets you access to subscriber-only posts and podcasts, the full archive, and the ability to comment on posts. Plus a couple of rad stickers in the mail! Here’s what they’ll look like:

That photo, by the way, is of the Strom Thurmond Federal Building, a brutalist masterpiece by Marcel Breuer and the subject of my first-ever Brutal South newsletter. The graphic design is by Marc Cardwell.

When I lived in Louisiana, I got involved with Together Baton Rouge (and later Together Louisiana) through my church. They advocated for many things but one of the biggest campaigns when I was there was putting limits on the Industrial Tax Exemption Program, which was pretty out of control. They/we successfully got Gov. John Bel Edwards to pass an executive order so that the local school board and metro council (and maybe others, I'm not sure) have to pass new exemptions before they take effect and last year Baton Rouge actually said no to Exxon. It's definitely not a perfect system, but it feels like progress!

https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/article_bc60c32a-1d92-11e9-a7de-cf740e9ce3ef.html

The system is good, and I like it.