On August 12, 2017, the American neo-Nazi James Alex Fields Jr. rammed a Dodge Challenger into a crowd of counter-protesters at a far-right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.

When police caught up with Fields, his car still had blood and flesh on it, according to local newspaper The Daily Progress. Fields sat on the ground in handcuffs, said he was sorry, and asked if everyone was OK. When the officer told Fields that he had killed a woman, Fields began to cry.

By the time of Fields’ terrorist attack that killed Heather Heyer and injured 35 others, reactionary lawmakers in several states had already introduced bills to reduce or eliminate liability for people who ran over protesters with their cars — but they blanched at the news from Charlottesville. As the president walked back his public support for “very fine people” among the assorted white supremacists and neo-Confederates that day, legislators sheepishly abandoned their bills. Of the eight initial driver liability bills introduced in the states, none passed.

But lawmakers did not abandon their dream of using vehicular manslaughter to stifle political speech. They just waited a few years.

In response to the new wave of protests following the 2020 police murder of George Floyd, legislative bodies in at least 11 states introduced 18 new bills to reduce liability for people who run over protesters with their cars. Car rammings became a regular occurrence at racial justice protests. Now four states have laws on the books granting criminal or civil immunity to motorists who hit protesters with their cars, according to the US Protest Law Tracker: Florida, Iowa, Louisiana, and Oklahoma.

In his book The Anatomy of Fascism, the historian Robert O. Paxton describes a series of “dress rehearsals” (161) that prepared footsoldiers and everyday people to accept a program of mass murder. I think about the killing of Heather Heyer as one such rehearsal in our country. In the six-and-a-half years since the attack, not only did state governments begin to rationalize and legalize vehicular assaults on protesters, but a large portion of the general public seemed to get a libidinal thrill out of fantasizing about it. Look around on the highway today and you may still see vehicles with an “All Lives Splatter” sticker on the rear window.

“Local eruptions of vigilantism by party militants were encouraged by the language of Nazi leaders and the climate of toleration for violence they established,” Paxton writes. “The Nazi state, in turn, kept channeling the undisciplined initiatives of party militants into official policies applied in an orderly fashion.” (158)

Fascism has taken many forms in many countries. Paxton explains that most of these forms, from the cryptofascism of Austria’s Jörg Haider to the Catholic integralism of Brazil’s Ação Integralista Brasileira, did not reach the heights of power or the depths of depravity of their Italian and German counterparts. I want to be careful to say that there is no equivalence in scale between what our country is doing now and the Nazis’ genocide of European Jews.

The threat of fascism has been here for a long time, though. Each generation has to meet that threat and defeat it.

I am not going to try classifying the United States by Paxton’s rubric of fascism1 today. Neither am I interested in convincing current participants in the nationalist-authoritarian project that they are fascists. I am only trying to identify what some of our fellow Americans have been rehearsing, in some cases since the country’s founding, so that the rest of us can prepare for what they do next.

“The legitimation of violence against a demonized internal enemy,” Paxton writes elsewhere, “brings us close to the heart of fascism.” (84)2

Terror

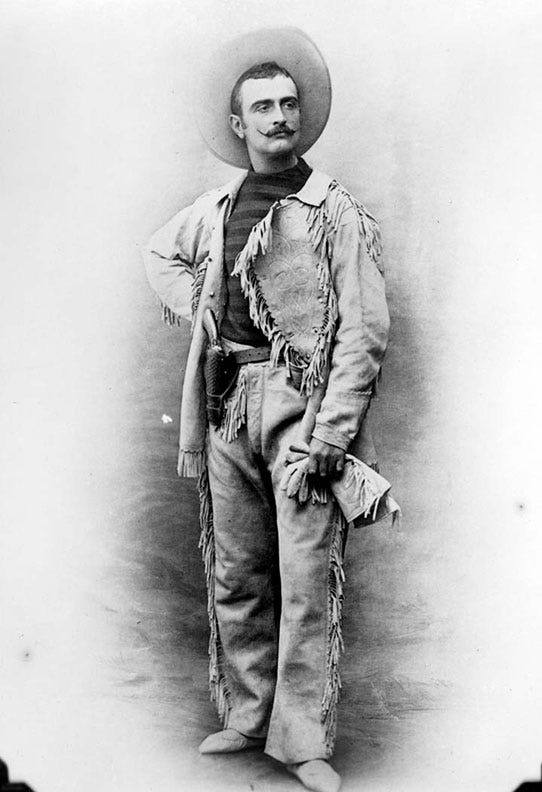

“The United States itself has never been exempt from fascism,” Paxton writes. He cites the Ku Klux Klan as possibly “the earliest phenomenon that can be functionally related to fascism,” before such phenomena swept across every European country in the 20th century. One proto-fascist leader, the French street gang thug Marquis de Morès, adopted a simmering antisemitic resentment and the affectation of a ten-gallon cowboy hat from his time as a failed cattle rancher on the North Dakota prairie in the late 1800s.

Paxton rattles off a list of antidemocratic and xenophobic movements that have taken root here in the United States:

“[T]he Native American party of 1845 and the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s … the Protestant evangelist Gerald B. Winrod’s openly pro-Hitler Defenders of the Christian Faith with their Black Legion; William Dudley Pelley’s Silver Shirts (the initials “SS” were intentional); the veteran-based Khaki Shirts … George Lincoln Rockwell, flamboyant head of the American Nazi Party from 1959 until his assassination by a disgruntled follower in 1967 … The Klan revived in the 1920s … Father Charles E. Coughlin gathered a radio audience estimated at forty million … North Dakota congressman William Lemke … The fundamentalist preacher Gerald L.K. Smith.” (201)

Publishing in 2004, Paxton also noted a rising “politics of resentment” as well as the curtailing of civil liberties in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

We still have wildcard organizations falling in and out of alignment with the regime in tense negotiations reminiscent of the Italian squadristi: militias of varying preparedness like the Oath Keepers, Proud Boys, and Three Percenters; propaganda organs like One American News Network, Libs of Tiktok, Turning Point USA’s Professor Watchlist, and the various aspiring race scientists who have found their niche here on Substack.

Lately these private groups have joined the state in attacking one small minority community that 20th-century fascists also persecuted: transgender people. On Nov. 22, 2022, two days after a mass shooting at Club Q in Colorado Springs, the anti-trans hate group leader Jaimee Michell went on Tucker Carlson’s then-massive cable TV talk show to predict further violence without explicitly calling on anyone to carry it out:

“We all, within Gays Against Groomers, saw this coming from a mile away, and sadly I don’t think it’s gonna stop until we end this evil agenda that is attacking children.”

Exception

One theme of the next four years will be that, whatever weapons we handed the U.S. government during the previous administration — whether Biden-era gang and terrorism charges levied against Stop Cop City activists, mayors’ bulldozing of homeless encampments, clampdowns on asylum hearings at the border, recriminations against pro-Palestinian campus protesters, or the routine dehumanizing abuse heaped on people in our prisons — the current administration will wield those tools against a growing list of its chosen enemies.

This year plainclothes federal agents have been abducting immigrants and political dissidents and shipping them to locations in global prison capitals like Louisiana, or even to foreign prisons where the administration washes its hands of responsibility. On April 13, Trump mused on TV about sending U.S. citizens to El Salvador’s notorious Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo (CECOT), just a few short weeks after he started defying court orders and shipping immigrants there.

“We have documented systematic physical beatings, torture, intentional denial of access to food, water, clothing, health care,” Noah Bullock of the human rights watchdog group Christosal told PBS of conditions in El Salvador’s prison system. “Skin disease is rampant. It's more likely that prisoners in the other prisons have scabies on their skin or even signs of physical abuse than the tattoos that you see in the images that are often projected from CECOT.”

The rationale for sending people to these facilities is paper-thin in each case: a speeding ticket, disfavored political speech, a tattoo that some cops construed as a gang symbol. If you fall for these excuses now, you will fall for every excuse until the state imprisons or kills someone you love.

These cages operate under a legal and rhetorical framework familiar to anyone who remembers the Global War on Terror: a “state of exception.” The state shreds civil liberties in the name of security, and it can practice unlimited cruelty as long as it maintains the specter of “terrorism” or “invasion” in the popular imagination. If fascism is, as the Italian antifascist Gaetano Salvemini saw it, a phenomenon of failed democracies that “felt the need to get rid of their free institutions,”3 it’s worth noting that we threw out some of our own free institutions a quarter-century ago.

Crucially, no new law enforcement agencies had to be created to carry out this year’s mass deportation campaign. The departments spawned during the George W. Bush administration — the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and its agency Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) — are now in the hands of an even less accountable unitary executive. Officers of these same branches, or their deputies, are now bashing in car windows and abducting people in the streets. They are disappearing people.

So, in addition to what Ernst Fraenkel called the “normative state” consisting of agencies that still abide by rule of law, we have handed the new administration a ready-made “prerogative state” governed largely by whims. Few checks remain on the violence practiced by this second, parallel state.

Torture

There were rehearsals for torture within our own borders, and templates for the facilities to carry it out. Sheriff Joe Arpaio of Maricopa County ran an immigrant tent city in the blazing Arizona desert for 24 years starting in 1993 and described it, in his own words, as a concentration camp.

Arpaio came under federal investigation for racial profiling and was eventually convicted of criminal contempt of court in July 2017, only to be pardoned the next month by President Trump.4

Other rehearsals took place outside U.S. borders. The United States’ global archipelago of black sites is still little understood and zealously hidden from public oversight, but one name has become emblematic of the entire system: Guantánamo.

The military prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, recently re-entered the American public consciousness when Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem posed for pictures with a military cargo plane depositing migrant detainees near a hastily constructed tent city there.

The function of Guantánamo Bay is to hold people indefinitely without charges. United States personnel have routinely tortured people at the facility with the full blessing of high-ranking bureaucrats like Marshall Billingslea and Donald Rumsfeld, who still walk free of the International Criminal Court.5

Guantánamo Bay was never a mega-prison. It held about 680 people at its peak in 2003, and one former Navy lawyer later described it as “America’s tiniest boutique prison.” Former President Barack Obama promised to close the facility but failed to do so from 2009 to 2017. Joe Biden made the same promise but instead spent millions of dollars on upgrades including a new secret courtroom.

The current administration has announced a plan to detain 30,000 people at Guantánamo.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi, a Mauritanian man who survived 14 years of physical, mental, and spiritual abuse at Guantánamo, did his best to establish bonds of human empathy with his captors. He wrote a book called Guantánamo Diary, heavily redacted at first by the U.S. government, in which he wondered what people on the outside thought of the hellhole they had built.

“What do the American people think? I am eager to know,” Slahi wrote. “I would like to believe the majority of Americans want to see justice done, and they are not interested in financing the detention of innocent people.” The reality is that most Americans don’t think about it at all.

There is a tendency to think of the United States’ moral failings as an aberration. But this is a country whose most progressive president invoked wartime powers under the Alien Enemies Act to unjustly imprison 120,000 Japanese Americans. This is a country that abducted Native children and indoctrinated them in boarding schools as a matter of federal policy for 150 years.

Observing the final years of the Cold War, the German liberation theologian Dorothee Sölle wrote in her seminal 1990 essay “Christofascism” that the United States by then tended to export its violence far abroad through proxy dictatorships.

“[O]ne of the essential differences between [U.S.] and European fascism is, in my judgment, the geopolitical fact that nowadays the concentration camps are not close to Weimar or Munich, but are far away: in El Salvador, in the Philippines, in South Africa, and wherever the great world power permits or encourages torture and murder, or has done so in the past.”

The School of the Americas, where the United States trained death squad captains to do its dirty work in El Salvador during the Cold War, is still operating in Georgia under the rebranded name Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC). The United States still forges strategic alliances with ethnonationalist authoritarians when it’s geopolitically convenient. And El Salvador’s president Nayib Bukele has opened a dungeon where the U.S. president intends to send his enemies.

Death

Paxton, in The Anatomy of Fascism, is careful to say what fascism is not. It is not the project of a single charismatic leader, but the project of many people in a particular milieu of mass politics, government stagnation, and wounded nationalist resentment. It is not an ideology; or to the extent that it expresses certain ideas, those ideas are loosely defined and less important than the actions of their adherents.

One thing the 21st-century U.S. shares in common with 20th-century fascist governments is a legal and logistical apparatus for state murder of captive civilians.

The German government compiled a list of those it deemed “criminally insane,” with a heavy preference for those it also deemed racially inferior. The state began killing these people with carbon monoxide gas at Brandenburg Euthanasia Center in January 1940. The first time the state tested the insecticide Zyklon-B on humans, it was to kill 600 Soviet prisoners of war at Auschwitz in September 1941. These were horrific crimes in themselves, but we know in retrospect that they were also rehearsals.

Whereas most industrialized democracies have ended the practice of capital punishment, several U.S. states are currently positioning themselves at the cutting edge of execution technology. Leading international pharmaceutical companies are no longer willing to sell to death-penalty states, so some state governments have resorted to experimental poison cocktails and chemicals sold by illicit black-market dealers.

The state of Arizona purchased a solid brick of potassium cyanide in December 2020 to begin manufacturing hydrogen cyanide, better known by its trade name Zyklon-B. Louisiana has resumed nitrogen gas suffocations, over protests from members of the state’s Jewish community. Executions by lethal injection have been botched and delayed, and some of the states’ victims have drowned as their lungs filled with fluid.

The shock of the news headline fades with each subsequent execution. The killings become routine. Those without a seat in the execution chamber can comfort themselves with the thought that maybe certain people were disposable after all.

What is there to say about politicians, states, and countries that work so doggedly, and with such “scientific” rigor, on the projects of terror, imprisonment, torture, and killing? In the death chambers, in the prisons, in the streets, in the statehouses, in the courtrooms, in the camps — what are they rehearsing?

***

Page number citations are from the 2005 Vintage Books edition of The Anatomy of Fascism. You can order a copy from Bookshop via my affiliate link if you like.

Paxton’s capsule definition of fascism, which he doesn’t reveal until the final chapter, is this: “Fascism may be defined as a form of political behavior marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion.”

Paxton, for his part, has changed his mind a few times on whether to classify the Trump administration as fascist. In 2017 in Harper’s he insisted on calling it plutocracy rather than fascism; in January 2021 in Newsweek he said Trump’s incitement of the Capitol putsch crossed the line into fascism; in October 2024 he told The New York Times that he still believed Trumpism to be fascist but that using the word is in no way politically helpful.

Opera de Gaetano Salvemini, vol. VI, Scritti sul fascismo, vol. I, p. 343 (Citation from Paxton; I can’t read a word of Italian.)

Long before 2017, Arpaio and Trump found common cause in the “birther” lie that sought to deny Barack Obama’s citizenship; Trump might as well have been deputized into Arpaio’s Cold Case Posse.

Long after completing his War Department role under Bush II, Billingslea served from 2017-2021 as our country’s Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Terrorist Financing. In 2019 he was briefly nominated to serve as Undersecretary of State for Civilian Security, Democracy, and Human Rights, which would have made him the highest-ranking official in the executive branch responsible for U.S. human rights policy.