The hell that we built

Guantánamo Bay is an obscenity and our country is morally stained until we bulldoze it

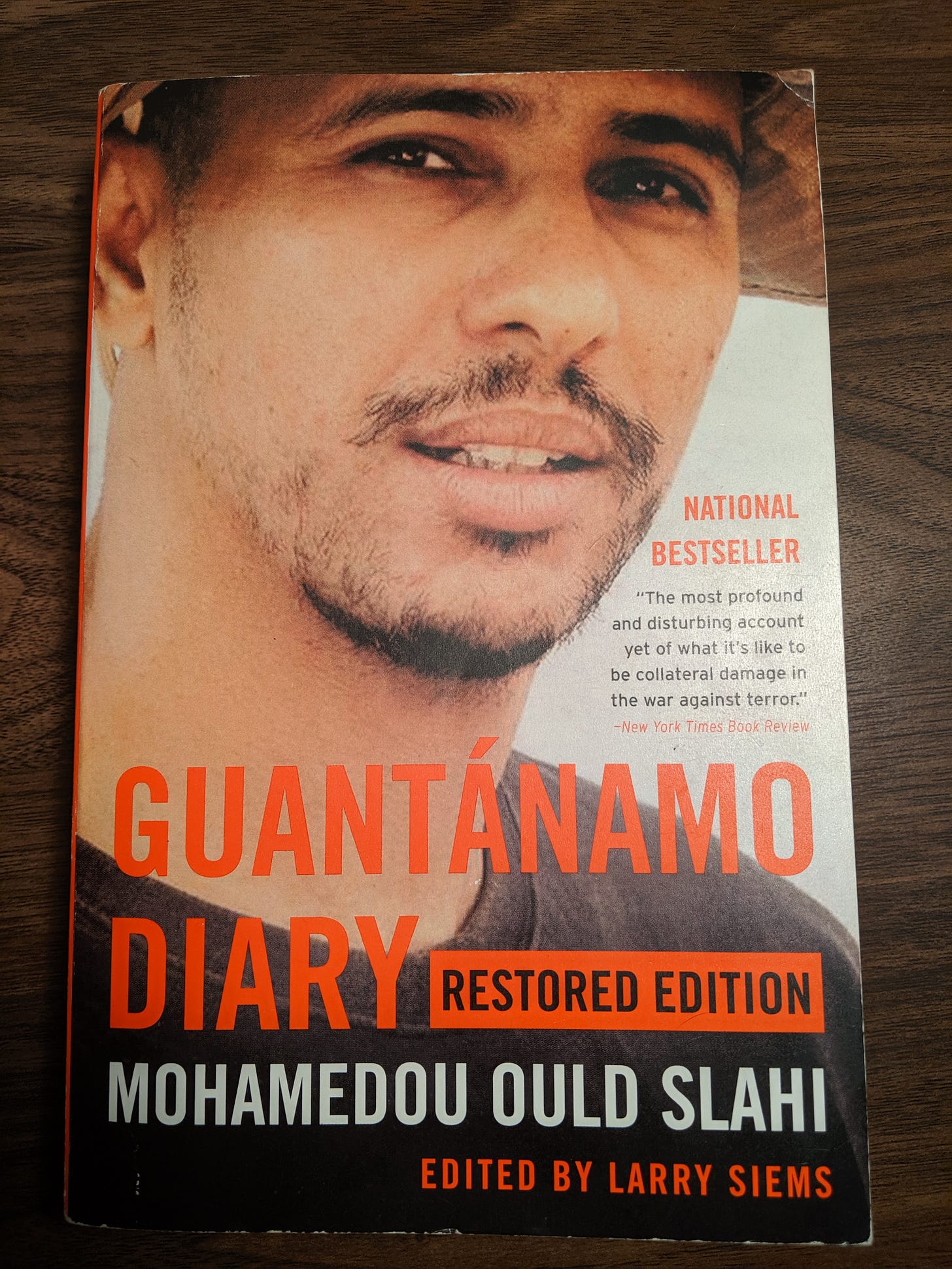

Next week is Banned Books Week, so this week I’m revisiting a book that our government really, really didn’t want you to read. It’s by Mohamedou Ould Slahi, who survived 14 years in Guantanamo Bay.

Marshall Billingslea, the man who recommended Slahi’s torture program, has not been tried at The Hague yet. Instead, he is Donald Trump’s nominee to serve as undersecretary of State for civilian security, democracy, and human rights. In that role he would become the highest-ranking official in the executive branch responsible for U.S. human rights policy.

By the way: If you live nearby and want to hang out with other bookish people, I’ll be giving a talk at Itinerant Literate Books in North Charleston on Tuesday Sept. 24 at 6:30 p.m. My tentative subject is “Dangerous Books for Dangerous Times: Reading Banned Literature in the Trump Era.” RSVP and get more information about Banned Books Week events on the Itinerant Literate Facebook page.

***

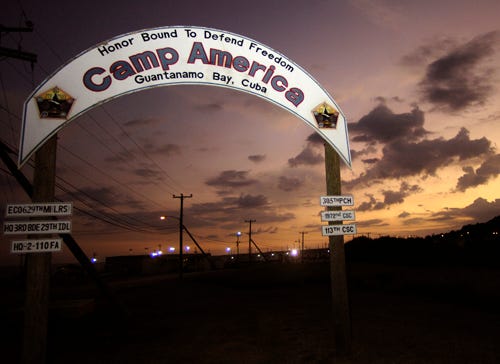

There’s an item in The New York Times this week about how you and I, the taxpayers of the United States of America, have spent $7 billion over the past 17 years operating what one former Navy lawyer called “America’s tiniest boutique prison.”

The article is about the Guantánamo Bay detention camp, an extralegal military prison in Cuba where we have detained men without charges, isolated them, tortured them, and psychologically worn them down until they had no choice but to make a confession.

I put as much stock in guided tours of Guantánamo as I put in guided tours of Pyongyang, so paragraphs like this one in the Times article smack of state propaganda when I read them:

“The 40 prisoners, all men, get halal food, access to satellite news and sports channels, workout equipment and PlayStations. Those who behave — and that has been the majority for years — get communal meals and can pray in groups, and some can attend art and horticulture classes.”

Sure, OK. Here’s what former detainee Mohamedou Ould Slahi wrote about the 14 years we held him at Guantánamo without a charge or a trial, in a book called Guantánamo Diary:

On the food: Guards at Guantánamo alternately starved Slahi, force fed him, and forced him to drink bottles of water until he vomited. “‘You have three minutes: Eat!’ a guard would yell at me, and then after about half a minute he would grab the plate. ‘You’re done!’”

On access to media: One officer in Cuba lied to Slahi and told him that the government had detained his mother, who was too frail to survive in prison. With nearly no access to the outside world, Slahi had no way of verifying that information. Slahi hand-wrote a 466-page memoir while being held at Guantánamo Bay, but it took 10 years and a lot of legal wrangling to get a (heavily redacted) manuscript into the hands of a publisher. When it finally made it to print, he was not allowed to read a copy of his own work. He did get access to a PlayStation though.

On prayer: Guards sent female officers to sexually humiliate Slahi, a practice described by other Muslim detainees and the CIA’s own internal documents. They denied him access to a Quran and repeatedly mocked him for praying: “‘Stop the fuck praying,’ [a guard] said loudly. I was by this time both really tired and terrified, and so I decided to pray in my heart.”

On horticulture: At one point near the end of Slahi’s account, after mind-bending spells of solitary confinement, Slahi did manage to cultivate a small garden where he grew sunflowers and herbs.

The officers who tortured Slahi were not rogue actors or bad apples. U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld signed a memo in 2003 approving the use of specific torture techniques in Slahi’s case, including the use of strobe lights and sleep deprivation. A Defense Department bureaucrat named Marshall Billingslea personally recommended the techniques to Rumsfeld, writing by hand on the memo, “We don't see any policy issues with these interrogation techniques. Recommend you authorize.”

Now, I know it’s possible we’ve cleaned up our act at Gitmo since Slahi’s book was published in 2015. It’s also possible Slahi was lying or exaggerating about his treatment. It is remotely possible that he was actually guilty of some terrorist plot, although my country in all its cunning wasn’t able to pin a single charge on him.

The moral challenge of Slahi’s book, and of the long proven track record of human rights abuses at Guantánamo Bay, remains.

“Let’s say I am criminal,” Slahi wrote. “Is an American criminal holier than a non-American?”

***

The Times article makes one oblique reference to inhumane treatment on the base, explaining that the Navy shipped a portable MRI machine to Guantánamo in 2017 to test prisoners for brain damage caused by torture.

Otherwise it reads like an accounting ledger, a simple “document dump” story. In its most dramatic moments, the story includes a few eye-popping dollar figures showing Guantánamo to be the world’s most expensive prison.

Guantánamo is just one island in the United States’ carceral archipelago. Slahi wrote that he was initially tortured and interrogated at CIA black sites in Jordan and Afghanistan, and officials in his home country of Mauritania were complicit in his kidnapping as well.

Closing Guantánamo wouldn’t put an end to the United States’ global empire, and it wouldn’t even put a dent in the mass incarceration of our own citizens. It’s still worth closing.

Barack Obama made a half-hearted effort to shut the place down, signing an executive order to that effect on his third day in office in 2009. The order went nowhere, stymied by surmountable logistical problems and a recalcitrant Congress.

In January 2018, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to keep the base open after promising on the campaign trail to “load it up with some bad dudes.”

Even when he was held in solitary confinement, Slahi sensed that his imprisonment carried political importance outside the walls of his cell. He wanted to believe the American people weren’t all as cruel as his captors, and that even some of his captors were decent people making the best of a bad situation.

“What do the American people think?” Slahi wrote. “I am eager to know. I would like to believe the majority of Americans want to see justice done, and they are not interested in financing the detention of innocent people. I know there is a small extremist minority that believes that everybody in this Cuban prison is evil, and that we are treated better than we deserve. But this opinion has no basis but ignorance.”

What do the American people think? For the most part we don’t think about it at all. The last public opinion survey I could find on the topic was a Rasmussen poll of likely voters from July 2017. At the time, 53% of respondents said they wanted Guantánamo to stay open, and 55% supported sending new terrorism suspects there.

These views are “extremist” as Slahi wrote, but they are not in the minority. When a proposal arose in 2012 to shut down Guantánamo and relocate its detainees to military brigs on the U.S. mainland, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-South Carolina) had this to say about it:

“Simply stated, the American people don't want to close Guantánamo Bay, which is an isolated, military-controlled facility, to bring these crazy bastards that want to kill us all to the United States. Most Americans believe that the people at Guantánamo Bay are not some kind of burglar or bank robber. They are bent on our destruction. And I stand with the American people that we're under siege, we're under attack, and we're at war."

One of the brigs where they would have probably relocated the prisoners is in a town called Hanahan, not far from where I live. I did not then, and I do not now, feel that I am under siege. Every day that the prison of Guantánamo Bay remains standing, the fact should lay siege to our consciences instead.

***

What happens to a country when it abides an open injustice for 17 years? Is there any way to contain that sort of moral rot? Or does it spread, infecting other institutions until it reaches the point of the soul?

Slahi had some time to think about this. After periods of anger, he freed himself, in a sense, by showing mercy to his captors. For the sake of his own spiritual wellbeing, and maybe for the sake of his sanity, he considered the plights of the guards and tried to connect with them.

“When I looked at the history of slaves, I noticed that slaves sometimes ended up an integral part of the master’s house,” he wrote. Like chattel slavery, the institution of torture colors our entire national character, and the people we terrorize are a part of our story.

Consider the arc of Slahi’s story: Snatched up by the government on false pretenses, alienated from his family, despised for his faith and the color of his skin, held in chains on a remote island, tortured by sadists, and censored by bureaucrats. He experienced America’s oppression in nearly all of its forms. We did everything but kill him.

So when I read about the expense of Guantánamo, I am of course disgusted and think of how that money could be better spent. But I am more troubled by the moral cost. These things are done in our name.

Forty men remain in custody at Guantánamo Bay, and only eight have been charged with terrorism or war crimes. Some of them should have been taken off the island long ago, including Toffiq al-Bihani, who has been cleared for transfer since 2010, according to Amnesty International.

Does the formula of democratic representation work backward as well as forward? When the government does something on my behalf as a citizen and taxpayer, am I in some way complicit? How can I ever atone?

***

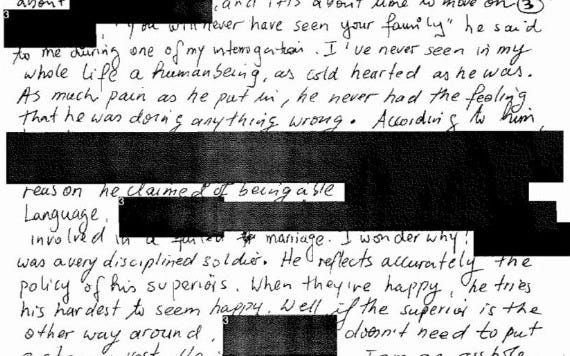

Originally published in 2015 while Slahi was still in captivity, Guantánamo Diary was re-released as a paperback in 2017 after his release. This new “restored edition” includes all of the sections that censors had redacted, filled in from memory by Slahi and his editor Larry Siems.

Aside from being necessary reading and a triumph of the human spirit, the restored edition is a unique literary experience, with the censor’s markings indicated by a gray outline. The censor hovers over the text like a minor character in the story, and we’re left to ponder and scrutinize the censor’s motivations. There is something that feels righteous about finally reading the pages that were once covered almost entirely in black bars. You can buy the book from Hachette Book Group or at your local bookstore.

Since his release in 2016, Slahi has been unable to leave his home country of Mauritania. The government has denied him a passport for reasons that remain unclear. The problem became urgent earlier this year when Slahi sought to travel to Germany for medical care. He has told reporters he needs treatment related to the chronic pain he has suffered because of torture. LitHub ran an interview with him about his ordeal in February and provided a link to a petition you can sign on Slahi’s behalf, addressed to Mauritania’s Ministry of the Interior and Decentralization.