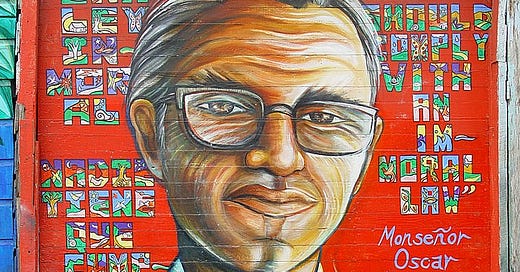

On February 17, 1980, Archbishop Óscar Romero of San Salvador wrote a letter to U.S. President Jimmy Carter. At the time, the U.S. government was giving supplies, training, and intelligence to El Salvador’s Christian Democratic Party military government, whose death squads had begun a campaign of kidnapping, torture, and mass murder in the name of rooting out communists.

Romero tried appealing to Carter as a man of Christian faith:

Because you are a Christian and because you have shown that you want to defend human rights, I venture to set forth for you my pastoral point of view concerning this news and to make a request …

If it is true that last November "a group of six Americans were in EI Salvador … providing $200,000 in gasmasks and flak jackets and instructing about their use against demonstrators," you yourself should be informed that it is evident since then that the security forces, with better personal protection and efficiency, have repressed the people even more violently using lethal weapons.

For this reason, given that as a Salvadoran and as archbishop of the Archdiocese of San Salvador I have an obligation to see that faith and justice reign in my country, I ask you, if you truly want to defend human rights, to prohibit the giving of this military aid to the Salvadoran government. Guarantee that your government will not intervene directly or indirectly with military, economic, diplomatic or other pressures to determine the destiny of the Salvadoran people.

Here we had a Catholic archbishop writing to a Baptist president asking him to stop backing the Christian Democratic Party in his country. Romero was appealing to some universal qualities of Christian doctrine in an attempt to transcend international and ideological borders. But Christendom has been at war with itself nearly from the beginning, and the Cold War was no exception.

Reading Saint Óscar Romero’s letter this week, I was struck by the two Christianities on display: one working to maintain the present order (the Christianity of President Carter and the Cold War capitalists), the other working toward liberation (the Christianity of Romero and the postcolonial left). Adherents to both Christianities could look across the aisle and see nothing legibly “Christian” on the other side.

In my own narrow provincial context, I recognize the same two tendencies in Christian political advocacy — toward maintaining hierarchical order, on the one hand, and toward winning liberation from hierarchical oppression, on the other. In South Carolina, the loudest and largest factions calling for the persecution of transgender people, the end of reproductive rights, deference to corporate interests, and the exclusion of liberatory teaching from classrooms are Christians. A smaller but no less passionate fellowship of progressive Christians stands opposed. I count myself among the second group.

Last month we had a clarifying moment in the national discourse after Republican Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia proclaimed her allegiance to the politically ascendant strain of Christianity in the U.S.A.

"We need to be the party of nationalism and I'm a Christian, and I say it proudly: We should be Christian nationalists," she said onstage at a Turning Point USA Student Action Summit in Tampa, Florida.

She was saying the quiet part out loud. I tend to agree with the assessment of Dean Detloff and Matt Bernico, who recently said on The Magnificast that “Christianity is not what we hope it is.” Greene’s view of the world is a dominant view of mainstream religion here. Every U.S. president has been a self-proclaimed Christian, and each one has embraced nationalism to one degree or another. Some, like Trump and Bush II, rode into power on a wave of explicit Christian nationalism, while others quietly bent the knee at Christian nationalist ceremonies like the National Day of Prayer.

There is a tendency among those of us who reject Greene’s vision to exoticize our country’s theological-political problems. In memes and heated opinion columns and Facebook comments, we warn in ominous tones that the religious right is adhering to “American Sharia” or building an “American Taliban.” This is hardly a new move. In his 1967 essay “Civil Religion in America,” Robert Bellah noted that progressives were wary of conservatives building an “American Shinto” to rival Japan’s.

But we don’t have to look elsewhere for precedent or analogies. Christianity has been an animating and justifying force throughout our history of colonialism, genocide, imperial expansion, anticommunist spycraft, torture, mass incarceration, and military misadventure. The doctrine of discovery and Manifest Destiny were Christian doctrines, as were the innumerable sermons justifying chattel slavery, Jim Crow, and massive white resistance to desegregation. The global forever-war of the 21st century was sold to us at times as a holy war waged by a Christian nation, reaching its logical nadir during the Trump administration’s Muslim immigration ban.

So no, we are not under threat from an “American Al Qaeda” or a U.S. Juche. The dominant oppressive theology on the North American continent is that of U.S. Christianity. Christofascism, if you will. It has its own sordid history.

Returning to the Cold War: Archbishop Romero was not alone in his predicament when he pleaded, first with Pope John Paul II and then with President Carter, for an end to military oppression in his country. In his 1971 book A Theology of Liberation, the Peruvian priest and theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez wrote:

Frequently in Latin America today certain priests are considered “subversive.” Many are under surveillance or are being sought by the police. Others are in prison, have been expelled from their country (Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, and the Dominican Republic are significant examples), or have been murdered by terrorist anti-communist groups. For the defenders of the status quo, “priestly subversion” is surprising. They are not used to it. The political activity of some leftist groups, we might say, is — within certain limits — assimilated and tolerated by the system and is even useful to it to justify some of its repressive measures; the dissidence of priests and religious, however, appears as particularly dangerous, especially if we consider the role which they have traditionally played.

Romero begged Carter not to put a thumb on the scale for people who were slaughtering his congregants and neighbors. But by the time Romero sent his letter, members of the Carter administration were well aware of his beliefs on the matter. In fact, they had placed a target on his back for expressing those beliefs already.

Seventeen days before Romero sent his letter, on Jan. 31, 1980, U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski 1 had written a letter to Pope John Paul II asking him “to ensure that the Church plays the responsible and constructive role of moderation.” Most of Brzezinski’s letter was specifically complaining about Romero, who, while not a political radical, had become outspoken in his criticism of the U.S.-backed regime in El Salvador:

Impatient with the pace of progress of the moderate Revolutionary Governing Junta led by the Christian Democratic Party and reformist military officers, and increasingly convinced of an eventual victory by the extreme left, the Archbishop has strongly criticized the Junta and leaned toward support for the extreme left.

Through our frequent and frank dialogue with Archbishop Romero and his Jesuit advisors we have warned them against such a move … Our efforts to persuade them have unfortunately not proven successful.

On the evening of March 23, 1980, Romero gave a sermon on the radio calling on Salvadoran soldiers to resist orders and stop brutalizing their neighbors:

I would like to appeal in a special way to the men of the army, and in particular to the troops of the National Guard, the police, and the garrisons. Brothers, you belong to our own people. You kill your own brother peasants; and in the face of an order to kill that is given by a man, the law of God that says “Do not kill!” should prevail.

No soldier is obliged to obey an order counter to the law of God. No one has to comply with an immoral law. It is the time now that you recover your conscience and obey its dictates rather than the command of sin … Therefore, in the name of God, and in the name of this long-suffering people, whose laments rise to heaven every day more tumultuous, I beseech you, I beg you, I command you! In the name of God: Cease the repression!

On the evening of March 24, 1980, shortly after Romero celebrated Mass in a small hospital chapel, a gunman entered the chapel and shot Romero through the heart.

The assassination sparked protests, mourning, and international condemnation. Members of the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union refused to deliver U.S. military equipment bound for El Salvador. But the U.S. security state and the Carter administration hardly wavered in their diplomatic and material support for the Salvadoran government, which was just beginning a 12-year civil war that would kill 80,000 people, disappear 8,000 more, and displace at least a half-million refugees.

Even the site of Romero’s funeral became a massacre, with 30 to 50 people left dead after gunshots and explosions rocked the crowd. The slogan "Be a Patriot, Kill a Priest" appeared scrawled on walls and printed on flyers outside churches across the country. The threat to clergy was clear: Stand against us and you will be next against the wall.

No one was ever arrested or charged in Romero’s assassination, but we know who gave the order. As early as 1986, ex-U.S. ambassador Robert White reported to Congress that the assassination order had come from U.S.-backed politician and death squad leader Roberto D'Aubuisson, who was nicknamed “Blowtorch Bob” after his preferred method of interrogating prisoners.

D'Aubuisson had been trained at the School of the Americas, a training compound established by the U.S. Department of Defense for the purpose of equipping anticommunist forces across Latin America.

“During the 1980 election campaign, Ronald Reagan and his running mate George H.W. Bush repeatedly attacked Carter as being soft on communism and not doing enough in Central America,” Jeremy Scahill wrote in a recent synopsis of U.S. foreign policy in El Salvador.

Declassified documents show that Reagan and Bush knew what D'Aubuisson had done, but they maintained ties with him and even ramped up their support for the Salvadoran military government while they waged Christian culture wars at home. When the Reagan administration sent Elliott Abrams and a young Colin Powell on a fact-finding mission to El Salvador in 1983, they conveniently failed to report back on such right-wing war crimes as the Massacre of El Mozote, in which the Salvadoran Army murdered 811 civilians including young children in the shadow of a village church. Abrams told Congress that reports of the massacre were communist propaganda as he urged Congress to send more financial support for the Salvadoran military.

Today Elliott Abrams remains alive and free. He was appointed to a number of diplomatic and national-security positions under the Bush II and Trump administrations. The School of the Americas also remains in operation to this day. It has relocated to Columbus, Georgia, and rebranded as the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC). It continues to train Latin American police and military forces.

The same Jimmy Carter who ignored Romero’s plea and cast his lot with a Salvadoran torture regime is now seen by the world as a kindly old Sunday School teacher who builds Habitat for Humanity houses and putters around his Georgia hometown saying nice things about LGBTQ people. He is a Christian. So were Reagan and the Bushes. So was Romero.

“Archbishop Romero was the most loved person and the most hated person in this country," Ricardo Urioste, Romero’s personal aide, told the BBC in 2010. "And as Jesus, he was crucified."

For those of us who profess to follow Jesus, a multitude of Christianities present themselves to us, and we must choose which one to follow. Taking up Saint Romero’s cross today means rejecting the Christianity of the empire that murdered him.

***

Brutal South is a free newsletter about education, class struggle, and religion in the American South. If you would like to support my work, get some cool stickers in the mail, and read / listen to some subscriber-only content, paid subscriptions are $5 a month.

Bookshop // Twitter // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts

Yes, that’s MSNBC anchor Mika Brzezinski’s dad.

Carter certainly has some culpability here, but in fairness his administration did withdraw a lot of support for these regimes. This interview offers some interesting insights about that and how others stepped in to fill the void https://m.soundcloud.com/historiaspod/historias-123-molly-avery-on-pinochet-and-el-salvador

I like this piece because the error of American presidents is still ongoing. Biden is funding a war in Ukraine that could have been solved at a table. Biden has funded far too many wars in the past. In my opinion, the war is not about morals it is laundering money at the taxpayers expense. My fellow Americans deserve to have our taxes spent here at home. PMEASE continue to write because this subject has a great value. And I am sure you have many other valuable thoughts to be written