Like every president since Harry Truman, Joe Biden bowed to tradition and proclaimed a National Day of Prayer on May 6. It wasn’t enough for the hardline fundamentalists.

Congressman Mike Turner, an Ohio Republican, was miffed that Biden hadn’t specifically mentioned the word “God” in his proclamation.

“President Biden has embraced the far-left’s cancel culture that attempts to rewrite American history, tear down our institutions, and now, cancel God,” Turner wailed the next day.

With a week’s distance, I want to discuss the sermons preached by various politicians on this year’s National Day of Prayer. Some statements like Congressman Turner’s are bog-standard hog slop, dished out in the trough with a sprinkle of whatever moral panic is animating the right wing in any given year. Others are more nuanced.

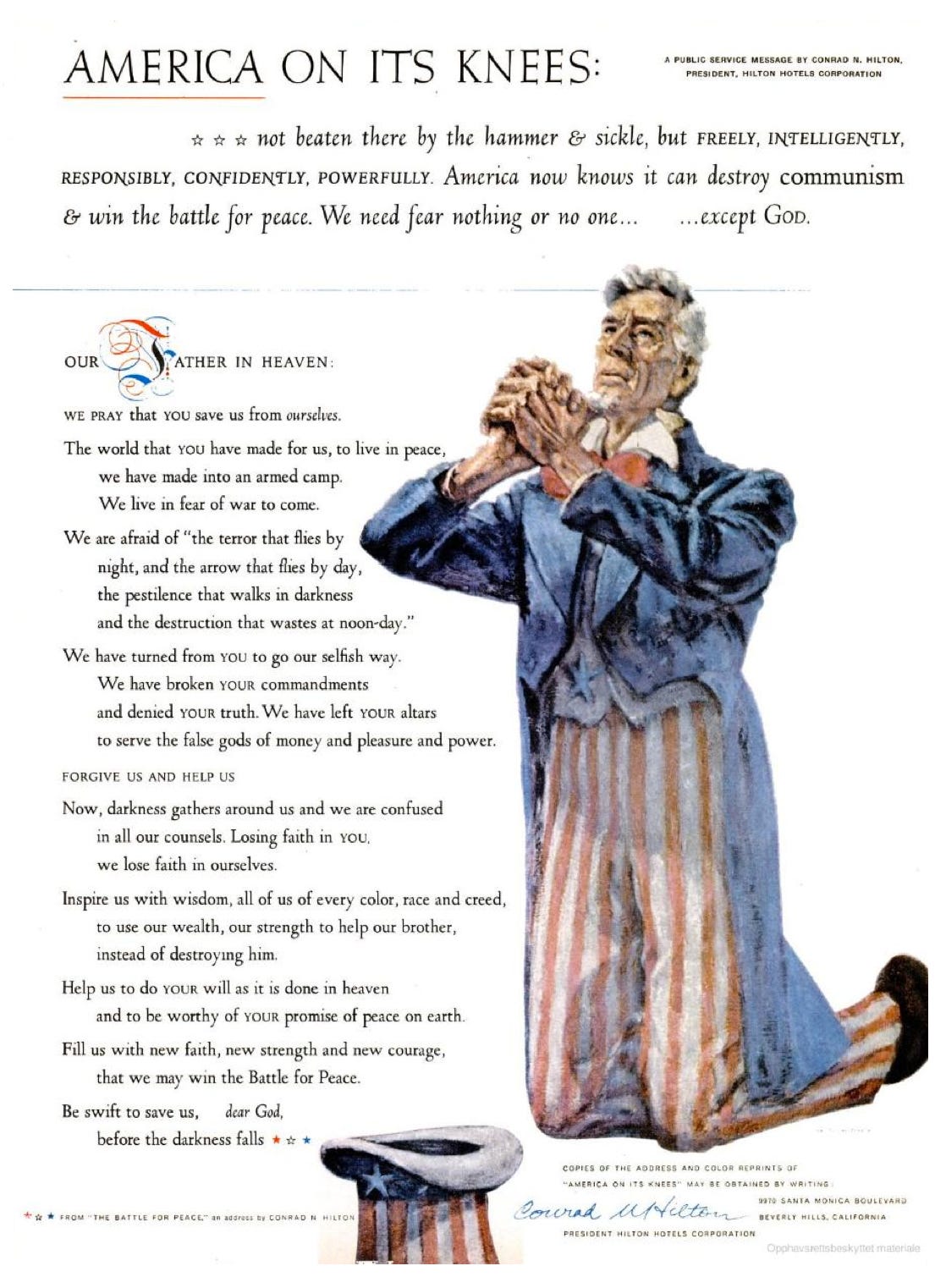

The modern National Day of Prayer law dates back to 1952. The radio evangelist Billy Graham told an audience of millions via the ABC network that he wanted Congress to set aside a “day of confession of sin, humiliation, and repentance, and turning to God at this hour.” Graham personally pushed the idea on President Harry Truman, who didn’t like the idea at first, according to historian Kevin Kruse.

“[Truman] still had reservations about public displays of prayer — in his diary that month, he noted that he abided by ‘the V, VI, & VIIth chapters of the Gospel according to St. Matthew,’ which were often cited for their injunctions against the practice — but he read the national mood and decided to acquiesce,” Kruse wrote in One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America.

With a go-ahead from Truman and House majority leader John McCormack, Congress resolved by unanimous consent “that the President shall set aside and proclaim a day each year, other than a Sunday, as a National Day of Prayer, on which the people of the United States may turn to God in prayer and meditation.”

From 1952 onward, even presidents who were not particularly religious practiced strict observance of the National Day of Prayer. As Kruse writes in his book, Nixon and Reagan had a more consistent attendance record at Day of Prayer events than at their own churches.

Truman should have listened to his conscience for once and told Billy Graham to take a hike. The National Day of Prayer is an open violation of the First Amendment’s non-establishment clause and an obvious sacrilege to anti-imperialist Christians. A federal judge declared the practice unconstitutional in 2010, but it keeps happening anyway. Religious communities with a love for racial and economic justice have started to wedge themselves into the event, but the National Day of Prayer remains at its core a fundamentalist, reactionary holy day.

To the extent that the National Day of Prayer gets news coverage, it’s usually in the form of a dull clip on the local evening news. The public prayer gatherings in Statehouses and town halls tend to come across as anodyne dog-and-pony shows where white-haired politicians hold hands with pastors and mumble a few pieties toward their constituents.

I think we should scrutinize these prayers for what they are: Political speeches that set policy agendas and grant religious legitimacy to the speakers. We should read them as closely and critically as a State of the Union (or State of the State) address.

***

With that angle in mind, here are two standout states from the 2021 National Day of Prayer.

Mississippi

Secretary of State Michael Watson delivered an apocalyptic sermon from the stage of the Mississippi Coliseum in Jackson, according to the Mississippi Free Press:

“I believe we need Christian men and women in office today more than ever before. And if you’re a believer, if you’re a member of the church, you understand the signs of the times right now. In the last few years, no more than ever before in the history of the church, we see the end times.”

In the course of the ceremony, speakers prayed against legal abortion, for schools to become “centers for revival,” for God to use the media to “root out evildoers,” and that “Israel’s enemies are confused and scattered.”

Covering the event for the Free Press, journalist Ashton Pittman highlighted the ways in which the National Day of Prayer has transformed since 1952. He identified a major shift in 1983 with the formation of the evangelical National Day of Prayer Task Force, which calls itself “Judeo-Christian” but has historically excluded Jewish speakers — as well as Muslims, Sikhs, Hindus, Buddhists, and even members of non-evangelical mainline Christian denominations.

The Task Force sets the theme for prayer events every year, and occasionally acts as a defendant in court cases challenging the constitutionality of state-ordained prayer. Theologically, the group has much in common with the Christian dominionism of conservatives like Mike Pence.

More specifically, the Task Force instructs Day of Prayer organizers to pray in accordance with the Seven Mountains mandate, a doctrine whose adherents include Donald Trump’s spiritual advisor Paula White. In Mississippi, as in other states, the prayer event was organized thematically around seven “mountains,” or spheres of influence: the family, the church, education, media, arts, the economy, and the government.

At one point in the ceremony, Mississippi Commissioner of Agriculture and Commerce Andy Gipson (who is also a Baptist pastor) prayed that God would “grow and bless” commerce in the state. But he also did something not often seen at National Day of Prayer events: He apologized.

Specifically, Gipson apologized to Chief Cyrus Ben of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, who was also present at the event, for “the many instances of violence, maltreatment, and neglect inflicted on native peoples by the citizens of the United States in times past.”

South Carolina

The organizers of South Carolina’s National Day of Prayer must have long ago given up the ruse of interfaith alliance or even bipartisanship. This year’s hourlong event on the Statehouse steps catered exclusively to fundamentalist Christians and socially conservative Republicans.

In one video of the event I found on YouTube, the first speaker delivers a sort of speech-prayer hybrid in a genre that will be familiar to anyone who grew up Southern Baptist:

Since the days of our nation’s founding fathers to this day, we have been very guilty, and for our iniquities we as a nation are now facing crisis after crisis — crises in homes and families, crises of violence and anarchy in our streets, crises of gross immorality in our media and culture, and crises in the halls of our local, state, and national governments as decisions are made that scoff at your holy character and your holy word. Have mercy on us, O God, have mercy.

It was a standard conservative prayer in that it chalked up every social problem to a matter of sin, not structural injustice. Crises in homes and families? Why, that’s because of our pervasive guilt as a nation, not our crumbling wages and jackbooted carceral state.

An excitable older gentleman got up to speak several times throughout the ceremony. I gather from context that he was Chris A. Smith, the organizer of numerous National Day of Prayer events in Columbia over the years. He was still buzzing from the news that state lawmakers had passed an abortion ban in February.

“Sen. Richard Cash in the Upstate has been a champion [of the] Christian conservative cause in the Statehouse from the Senate side,” Smith said. “He was the driving force behind us getting that heartbeat bill passed this year that is now the heartbeat law. So please give Richard a round of applause and thank him for what he is doing and the fight he is putting up for us as believers and followers of Christ.”

Gov. Henry McMaster took a turn at the microphone to read a tepid proclamation, then handed the show back to the other pastors and politicians. Smith wouldn’t let him go without calling him in for a round of praise.

“Four years ago, he made a promise to us: You pass the heartbeat bill and I’ll sign it, and our attorney general said he’d defend it,” Smith told the crowd. “Well, we got it passed, and promises made, promises kept, he signed it immediately afterward.”

Reproductive rights organizations immediately sued to challenge the abortion ban and quickly got an injunction from a judge who called the law “baffling” and “sideways” of the U.S. Constitution. Anti-abortion activists plan to challenge the ruling until it reaches the U.S. Supreme Court in an attempt to overturn Roe v. Wade.

***

Traditions that we would rightly condemn as theocratic cult behavior in any other country are hardly remarked on in the U.S.

Students here are compelled by social pressure to swear a loyalty oath every morning in school, church choirs sing patriotic hymns, politicians venerate the flag as a holy icon, our government officially hijacks May Day and proclaims it Loyalty Day every year, and war is prescribed as a blood sacrifice to secure the blessings of liberty.

As a Christian who abhors most of the things my country does in the name of Jesus, I’ve found it useful to think of traditions like the National Day of Prayer as sacraments of a separate faith: American civil religion.

The sociologist Robert Bellah proposed the concept of American civil religion in 1967 to describe a particular set of beliefs, symbols, rituals, and holidays that treat the American project as a quasi-religion. People tend to use the term pejoratively today, but Bellah, in his original essay “Civil Religion in America,” came off as somewhat agnostic about the merits of American civil religion:

The religious critics of "religion in general," or of the "religion of the 'American Way of Life,'" or of "American Shinto" have really been talking about the civil religion. As usual in religious polemic, they take as criteria the best in their own religious tradition and as typical the worst in the tradition of the civil religion. Against these critics, I would argue that the civil religion at its best is a genuine apprehension of universal and transcendent religious reality as seen in or, one could almost say, as revealed through the experience of the American people. Like all religions, it has suffered various deformations and demonic distortions.

Whether or not there are actual spiritual undercurrents to American life, the civil religion is undeniably real. We take in its symbols and sacraments every day without much notice.

Once a year, on the National Day of Prayer, that religion comes into sharp focus. If there are indeed demonic distortions at play, it’s a perfect time to observe them and call them what they are.

***

One Nation Under God is available to purchase via the Brutal South Bookshop page.

If you appreciated today’s newsletter, you might like this field guide to Christofascism that I wrote after the U.S. Capitol putsch in January.

You might also enjoy the podcast episode I recorded with Pastor Jim Conrad of Towne View Baptist Church in Kennesaw, Georgia. His church decided to accept LGBT members and was kicked out of the Southern Baptist Convention earlier this year. Click here to visit the episode page, or click here to subscribe to the Brutal South podcast for free via your podcast app of choice.

Brutal South is a free weekly newsletter and podcast. For $5 a month or $55 a year, you can help support my work and get access to subscriber-only content. Click Subscribe Now to get signed up.

Twitter // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts // Bookshop // Bandcamp