This is a reprint of an issue that originally went out to paid subscribers last year.

I was on a W.E.B. Du Bois kick in early May of 2022. I’d been reading parts of his John Brown biography for this piece on the brief but deep friendship of Brown and Harriet Tubman when I came across a 1920 essay of his (via Twitter, I think) called “The Souls of White Folk.”

I’m a latecomer to the Du Bois fandom; nobody assigned his work when I was growing up in South Carolina public schools, but I recognized the title of the essay as a play on his better-known 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk. This essay on white people was so cutting, so prescient, that I did a double-take to make sure it really was more than 100 years old.

One of Du Bois’ lasting contributions to philosophy is the concept of “double-consciousness,” which he sketched out in The Souls of Black Folk:

It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

This concept, and Du Bois’ description of Black Americans as living within a “veil,” have been passed down and analyzed and problematized for a century now. I’m struck by the clarity of his earliest explanations, though. He read widely and investigated deeply, and he synthesized what he saw and experienced into hard crystalline prose that still cuts today.

In “The Souls of White Folk,” Du Bois discussed the apparent invention of whiteness in the 19th and 20th centuries. He wrote from experience as a teacher, historian, public intellectual, and sociologist who had experienced the scorn and pity of white folks across the country — and who had also experienced cross-racial solidarity on trips abroad, and recognized a sickness in U.S. racial politics that was beginning to spread:

I do not laugh. I am quite straight-faced as I ask soberly:

“But what on earth is whiteness that one should so desire it?" Then always, somehow, some way, silently but clearly, I am given to understand that whiteness is the ownership of the earth forever and ever, Amen!

Now what is the effect on a man or a nation when it comes passionately to believe such an extraordinary dictum as this? That nations are coming to believe it is manifest daily. Wave on wave, each with increasing virulence, is dashing this new religion of whiteness on the shores of our time. Its first effects are funny: the strut of the Southerner, the arrogance of the Englishman amuck, the whoop of the hoodlum who vicariously leads your mob. Next it appears dampening generous enthusiasm in what we once counted glorious; to free the slave is discovered to be tolerable only in so far as it freed his master!

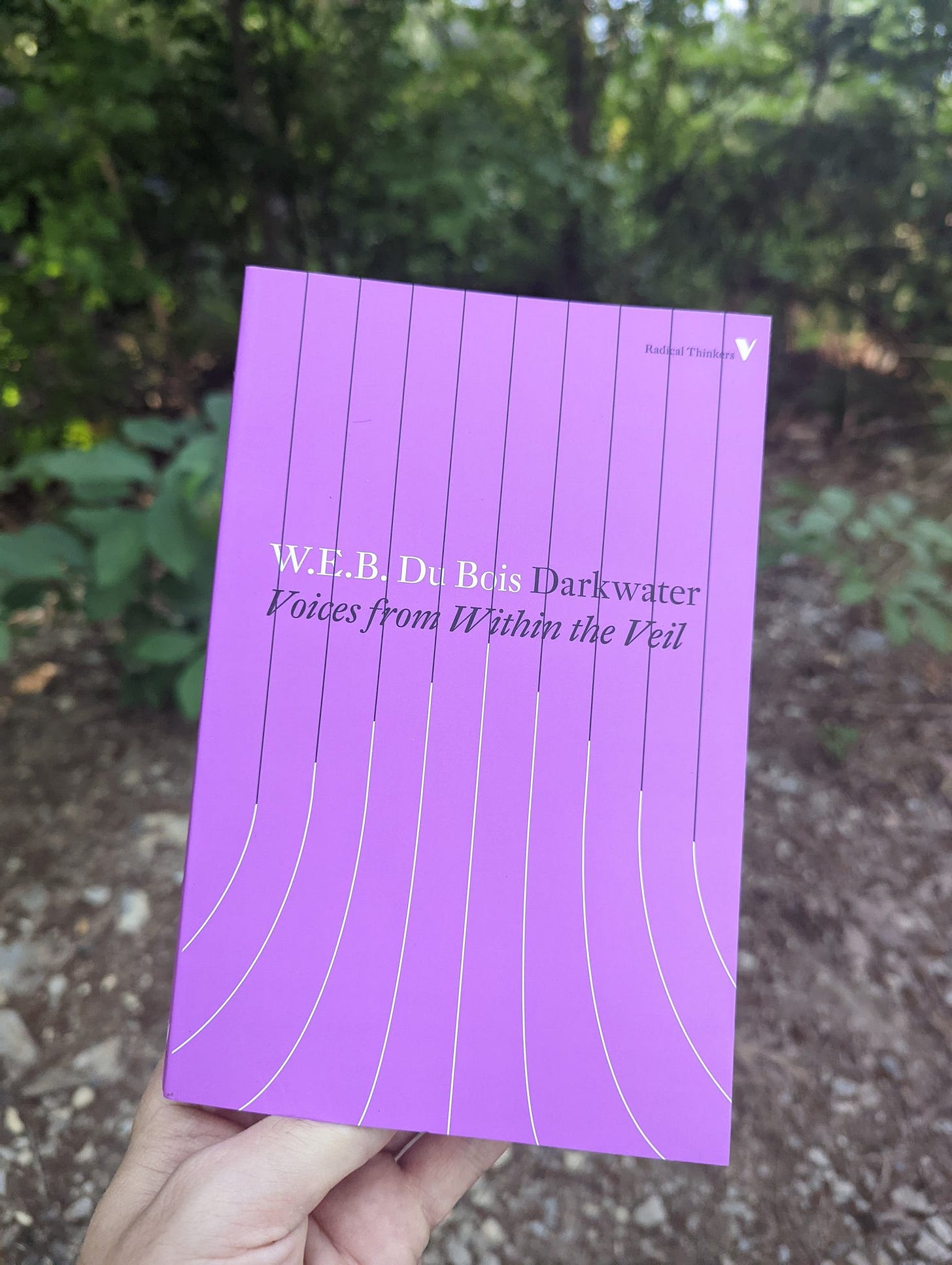

On the strength of this essay, I impulse-bought a Verso reprint of the book it was first published in, Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil.

It’s a strange, wide-ranging, experimental book. It is partly a collection of essays that originally appeared in The Atlantic, the Journal of Race Development, and other periodicals, but it’s more than that. The first chapter, “The Shadow of Years,” is a capsule autobiography. Other chapters include statistical analysis of racial politics and political economy, a proto-feminist rallying cry, and a plan for postcolonial independence of African nations.

In between the essays, he inserts philosophical poems and fictional sketches ranging from high fantasy to religious allegory to science fiction. The final essay, “The Comet,” is a darkly comic piece of dystopian fiction that laid some groundwork for Afrofuturism (it also could have made for a great Twilight Zone adaptation).

Connected by these creative ligaments, the essays take on a philosophical unity, building something that isn’t exactly a manifesto, but a framework for observing and critiquing the world.

The fourth chapter, “Of Work and Wealth,” draws on Du Bois’ 15 years as a teacher and his experience covering the East St. Louis Massacre as a journalist for The Crisis. Teaching history, economics, and sociology to Black students at Atlanta University, he struggled to discuss current events with the class in a way that was authentic but not despairing:

I fought earnestly against posing before my class. I tried to be natural and honest and frank, but it was a bitter hard. What would you say to a soft, brown face, aureoled in a thousand ripples of gray-black hair, which knells suddenly: "Do you trust white people?" You do not and you know that you do not, much as you want to; yet you rise and lie and say you do; you must say it for her salvation and the world's; you repeat that she must trust them, that most white folks are honest, and all the while you are lying and every level, silent eye there knows you are lying, and miserably you sit and lie on, to the greater glory of God.

Is it any different for teachers today, who can’t avoid parallels to the news when they talk about history? One difference is that, under white reactionary oversight, a Black teacher today can face firing, public humiliation, and even death threats for speaking plainly about racism. White demagogues accuse them of teaching “critical race theory;” here in South Carolina they have been hosting training seminars on how to film and expose teachers for the supposed sin of indoctrination

After deep reflection and anguish, Du Bois decided not to hold back. Particularly with classrooms of teenagers and young adults, he respected the students enough to draw their own conclusions. He insisted on providing them a critical framework:

In the teaching of my classes I was not willing to stop with showing that this was unfair,—indeed I did not have to do this. They knew through bitter experience its rank injustice, because they were black. What I had to show was that no real reorganization of industry could be permanently made with the majority of mankind left out. These disinherited darker peoples must either share in the future industrial democracy or overturn the world.

To Du Bois, a radical pedagogy was the only sane one. To deny the obvious to his Black students was foolish; to abandon them to despair was irresponsible. He wanted them to share in the wealth and beauty of the world, or else to overturn it.

Darkwater is available to read for free online via Project Gutenberg. If, like me, you prefer to read books on paper, the Verso paperback edition is available to order via Bookshop (this is an affiliate link, so I get a small cut if you order a copy).

If you’d like to read more about Du Bois, I wrote this reflection on his 1956 essay “Why I Won’t Vote”:

Before and after democracy

Before I start today’s issue, I want to mention a fundraising campaign by Fresh Future Farm, a nonprofit urban farm and grocery store working to fight food apartheid right here in North Charleston. I’ve seen the work that co-founder Germaine Jenkins and her team do firsthand, and I’m a big believer.

Bookshop // Twitter // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts