Before I start today’s issue, I want to mention a fundraising campaign by Fresh Future Farm, a nonprofit urban farm and grocery store working to fight food apartheid right here in North Charleston. I’ve seen the work that co-founder Germaine Jenkins and her team do firsthand, and I’m a big believer.

Over the weekend, Fresh Future Farm launched a capital campaign to expand into a 20-acre cooperative farm on some rural land. If you are looking for a worthwhile place to show a little solidarity, please check out the capital campaign announcement for more information on how you can donate or sponsor this life-giving work.

***

So you voted.

So you watched the council meetings, or the Statehouse debates, or the Congressional hearings, and you wrote letters or called your representative or traveled to the legislative chambers and gave testimony pleading for your government to please stop grinding the poor and repressing marginalized communities, and you might as well have yelled your complaints into a storm drain for all the difference it made.

So you geared up for the next election, threw your time and support behind a progressive challenger, only to see your candidate disappoint you, or get crushed by an avalanche of dark money, or get cheated out of a fair chance through gerrymandering and voter suppression.

What does democracy mean to you now?

In meaningful ways, some of us in the United States are already living in an era after representative democracy. The Wisconsin State Assembly, for example, has insulated itself from the will of its constituents through open Republican gerrymandering permitted by a U.S. Supreme Court with its own Republican supermajority.

Voters in South Carolina’s 1st Congressional District watched Republican Nancy Mace sail to victory in November, only to see a federal court rule in January that the 1st Congressional District was a classic racial gerrymander.

In Florida in 2018, nearly 65% of voters approved a constitutional amendment restoring voting rights to formerly incarcerated people — so in 2019 Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a bill requiring those voters to pay off legal fees before they register to vote (a poll tax, to use a term of art) and in 2022 a state attorney began prosecuting people for improperly registering to vote under the arcane new voting regime.

At least since Bush v. Gore, Republicans in the highest seats of power have cast any result but victory as illegitimate. Now all the old tricks and truncheons are back in style. In January 2021, just days before the Republican putsch in the U.S. Capitol, U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz made the ultimate Jim Crow callback when he invoked the explicitly racist Compromise of 1877 as precedent for throwing out election results.

In considering how we might take action after democracy is ended in this country, it’s worth revisiting how our forebears took action before democracy began — that is to say, before the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

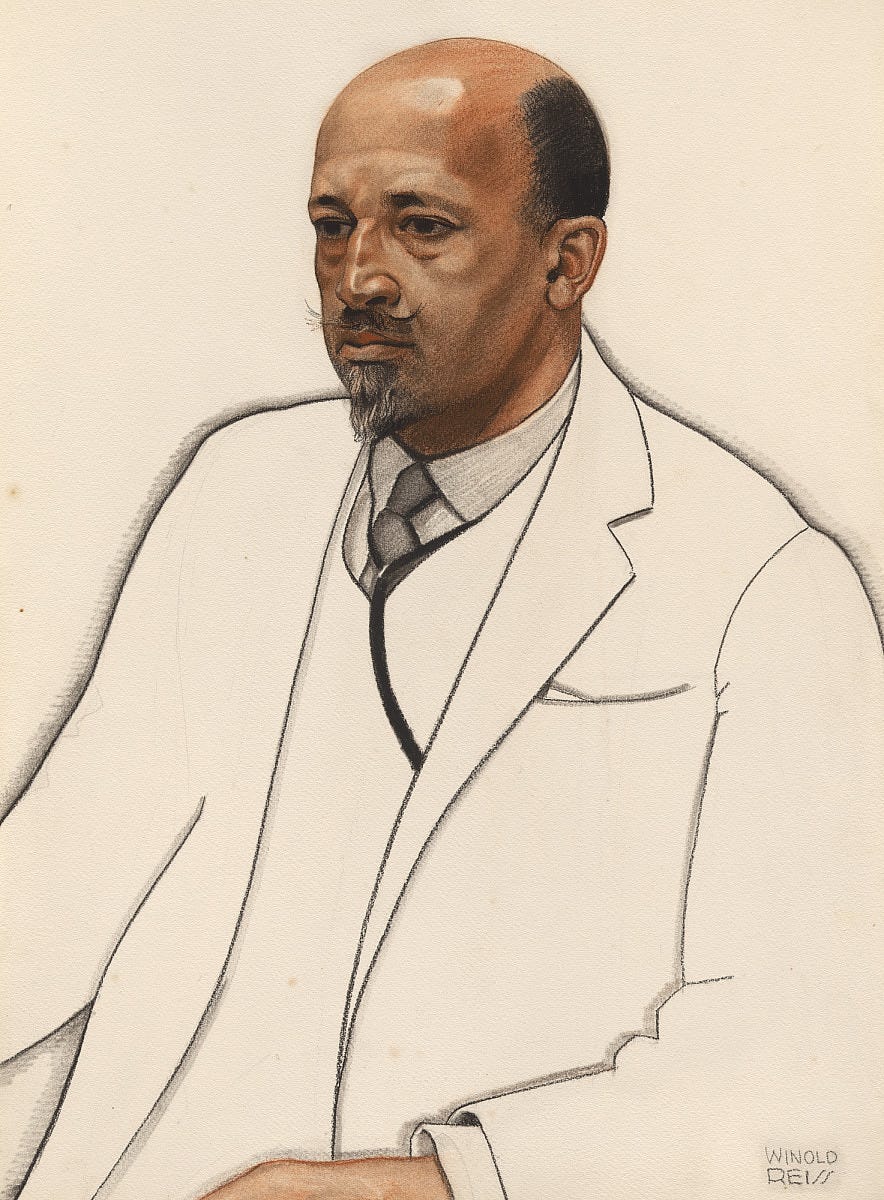

The socialist historian and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois was fed up waiting for his vote to count in 1956 when he wrote a short piece in The Nation titled “Why I Won’t Vote.” Disenfranchised as a Black man in the South, he had moved north and voted in elections for the most progressive available candidates for 32 years, but he didn’t see the use anymore. He was sick of third parties who neglected or disdained Black voters, from the Socialists all the way back to Teddy Roosevelt’s Bull Moose convention; he was sick of candidates from both major parties breaking promises to Black voters, if they promised anything at all. He spent 10 years back in the South and saw “democracy” there for the farce it was.

Du Bois wrote:

I have no advice for others in this election. Are you voting Democratic? Well and good; all I ask is why? Are you voting for Eisenhower and his smooth team of bright ghost writers? Again, why? Will your helpless vote either way support or restore democracy to America?

Is the refusal to vote in this phony election a counsel of despair? No, it is dogged hope. It is hope that if twenty-five million voters refrain from voting in 1956 because of their own accord and not because of a sly wink from Khrushchev, this might make the American people ask how much longer this dumb farce can proceed without even a whimper of protest.

Born in 1868 in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, U.S.A., Du Bois died in 1963 in Accra, Ghana. He was born during Reconstruction but did not live to see the second attempt at multiracial democracy in his home country, and in the final decade of his life he was rightfully tired of waiting. It’s a mistake to call this stance nihilism. His hope was in something bigger than electoralism, and as a result it was more durable.

Du Bois’ view of liberation transcended national borders; he was a scholar and advocate for democratic self-rule in postcolonial African nations. His view of democracy at home was similarly expansive, going beyond the voting booth and into the workplace. He saw that Americans would never be truly free until they cast off the chains of capitalism.

In 1920, he wrote in his essay “Of the Ruling of Men”:

In industry, monarchy and the aristocracy rule, and there are those who, calling themselves democratic, believe that democracy can never enter here. Industry, they maintain, is a matter of technical knowledge and ability, and, therefore, is the eternal heritage of the few … These are the ones who say: We must control labor or civilization will fail; we must control white labor in Europe and America; above all, we must control yellow labor in Asia and black labor in Africa and the South, else we shall have no tea, or rubber, or cotton. And yet, — and yet is it so easy to give up the dream of democracy? Must industry rule men or may men rule even industry? And unless men rule industry, can they ever hope really to make laws or educate children or create beauty?

Du Bois was writing in 1920 after a decade of pitched labor battles and growing union membership, though even those victories were short-lived and the labor movement was hampered by the racism of some of its own leaders. He had few illusions about the struggles that lay ahead.

As we read Du Bois’ words today, union membership in the U.S. is at an all-time low despite some high-profile organizing efforts, and electoral democracy is on the ropes in many of our states. Particularly here in the South, prospects are grim on both fronts.

The lessons we can take away from Du Bois are not as simple as “Don’t vote.” By all means, while we still have some form of democracy we should keep voting, keep fighting for better representation and the return of a fuller democracy. Keep up the pressure in the Statehouse and city council chambers even if it’s to the bitter end. I promise I’ll keep showing up where I can, too.

But if we are going to fight for democracy, I want to fight for a more expansive vision of democracy. We can have a country where wages and work conditions are not handed down from the authoritarian private government of the workplace, where decisions about our medical care are not made by insurance middlemen, where healthy food is a right and not a luxury, and where our public schools are not under financial and ideological attack by eccentric heirs and tycoons.

“Stop yelling about a democracy we do not have. Democracy is dead in the United States,” Du Bois wrote in 1956. “Yet there is still nothing to replace real democracy. Drop the chains, then, that bind our brains.”

***

“Of the Ruling of Men” (1920) is available to read at webdubois.org or in the essay collection Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil.

“Why I Won’t Vote” (1956) is available to read via World History Archives.

Bookshop // Twitter // Bandcamp // Spotify Podcasts // Apple Podcasts