“Fatherhood unlocks your true potential,” an apparently famous man tells his 2.7 million internet followers. “Fatherhood is alpha-motivation.”

The famous man holds a baby and sports a T-shirt with the slogan “JUST A REGULAR DAD TRYING NOT TO RAISE A COMMUNIST.”

Setting aside the fact that treating your child as a political prop is a good way to inadvertently raise a communist (and setting aside the unsealing of a Justice Department indictment days later indicating that this man, one Benny Johnson of Tampa, might have been receiving 6 figures a month from the Russian government for his work as an internet celebrity), he reflects the zeitgeist of this election season in certain parts of the American right.

In the natalist-to-eugenicist circles of U.S. politics, voters are expected to valorize parents and scorn the “cat lady” and “man child,” embodiments of liberal decadence who supposedly haven’t gained full entry to adulthood because they aren’t parents. The men hold their babies up like trophy fish; they talk about child-rearing as a means of social discipline for adults. 1

The timing is notable. In the 26 months since the Supreme Court ended the right to a safe and legal abortion in this country, as state governments have stripped away choices about reproduction primarily from women, the most off-putting men in media and public life have been extolling their own decision to become dads. The Court created a new reality, and now the intellectual rear guard is here to sanctify and rationalize that reality.

Some, like vice presidential candidate JD Vance, have even proposed that adults without children ought to have their votes diluted by giving extra votes to parents on a per-child basis. This is a revival of Demeny voting, an idea that recurs in societies where people are panicking about birth rates and demographic change. Parents, they argue, know best.

I’ll play the dad card here: Nine years into fatherhood, I can report that my children have not made me a more virtuous person. I am not a more fully realized man than my child-free friends. I have gained no special insights into The Future of The Republic.

Of course I have different obligations and priorities than before. I have new struggles and new joys. I sleep lighter and wake up earlier; I do a lot more laundry; there’s a hard stop on my working day when I have a youth soccer team to assistant-coach.

I can certainly change for my children, and I hope that I have. But I reject the notion that this is a path to self-actualization. Children are not born to help parents find themselves.

I owe my children unconditional love and all the happiness we can make. Still, morally speaking, what makes or breaks me is not the particular arrangement of people in my life, but the way I treat them. I can succeed or fail as a partner, coworker, neighbor, comrade, son, friend, and parent.

Men like Vance and Johnson valorize parenthood precisely as their political backers seek to force childbirth using the power of the state. We can see the outer edges of their ambition when, for example, right-wing pundits decry the existence of vasectomy clinics outside the Democratic National Convention: They were never content with banning safe abortions in the states under their control; they seek a less free world for everyone.

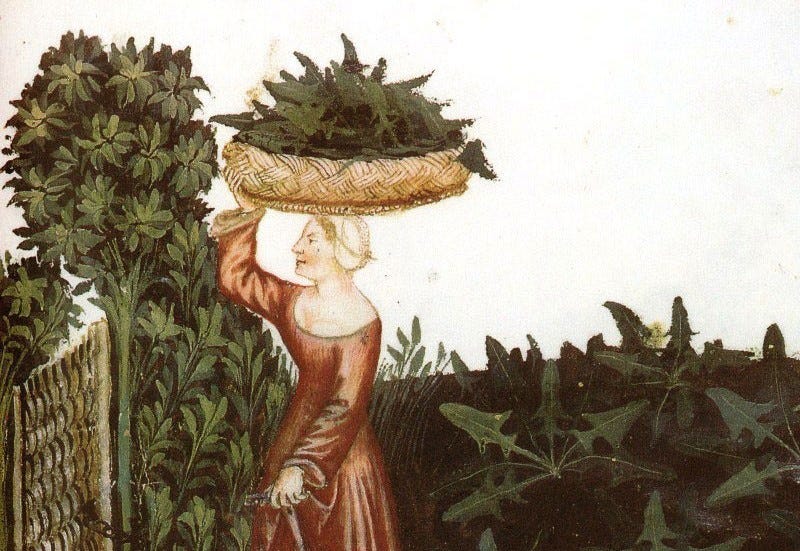

I’m in a little book club that has been reading Silvia Federici’s Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, and a recurring theme is how lofty doctrinal claims have overlaid and enforced control of reproduction by the state. In European countries during the long transition from feudalism to capitalism, as bosses in expanding markets demanded a steady supply of expendable low-wage workers, Federici notes “an almost fanatical desire to increase population,” coupled with severe penalties for long-practiced methods of contraception and abortion. New forms of surveillance arose; in France a royal edict of 1556 required women to register every pregnancy. Show trials and executions for witchcraft were not far behind.

“[F]rom now on their wombs became public territory, controlled by men and the state, and procreation was directly placed at the service of capitalist accumulation,” Federici writes.

When capitalism ends us or we end capitalism, familiar panicked voices will prescribe childbirth and parenting as a cure for what ails us at the personal and societal level. But it didn’t save the women of the medieval or early modern eras, and it won’t save any of us this time either.

For more about the conservative notion of parenthood as a disciplining influence on adults, check out Episode 31 of the podcast In Bed with the Right, “Pro-Natalism.”