New fiction: Pleasant Grove

'I ducked into the alley of oaks that led to the smoldering ruins of Pleasant Grove Plantation'

I’ve struggled to sleep and struggled to write this week. The problems are probably connected.

Sometimes when I can’t sleep I sit up counting the stray fireworks and reading passages from W.E.B. Du Bois’ Darkwater or Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s Essays Toward Liberation. I think they both have something to say about our country’s present relapse, but I don’t have anything new or insightful to add to what they’ve written. I also re-read Robert Bellah’s 1967 essay “Civil Religion in America” last night, and I tried writing an essay of my own about developments in the U.S. civil cult since 9/11, but I had nothing new to add.

What’s the use in one more helpless lamentation? I’ll write an essay when I have something to say. In the meantime I’m publishing a piece of fiction I wrote for the Piccolo Spoleto Festival back in early June. In a long-running tradition that usually takes place in the alley beside Blue Bicycle Books, a handful of local writers take turns reading original short stories that start with the phrase “I ducked into the alley…” I was honored that Jonathan Sanchez invited me to contribute to the event in 2020, and this June, after two years of COVID delays, I finally got to read to an audience.

A note about terminology: I use a word in this story that I don’t, as a rule, use in conversation or my writing, and that word is “slave.” Slavery is not an identity; it is a condition imposed on one person by another. I would normally say “enslaved person,” but the phrase wouldn’t work within the historical context of the story, which is set in the U.S. South in 1863.

***

Pleasant Grove

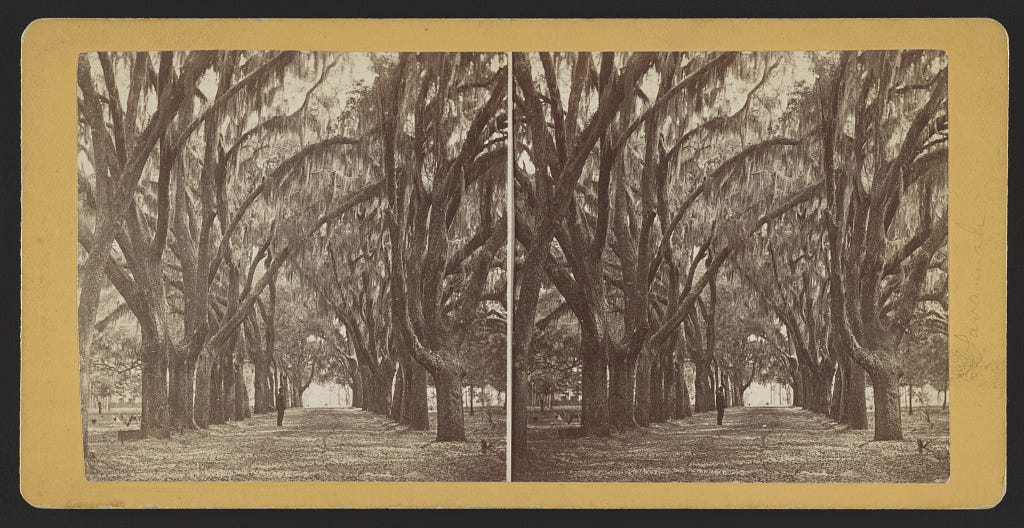

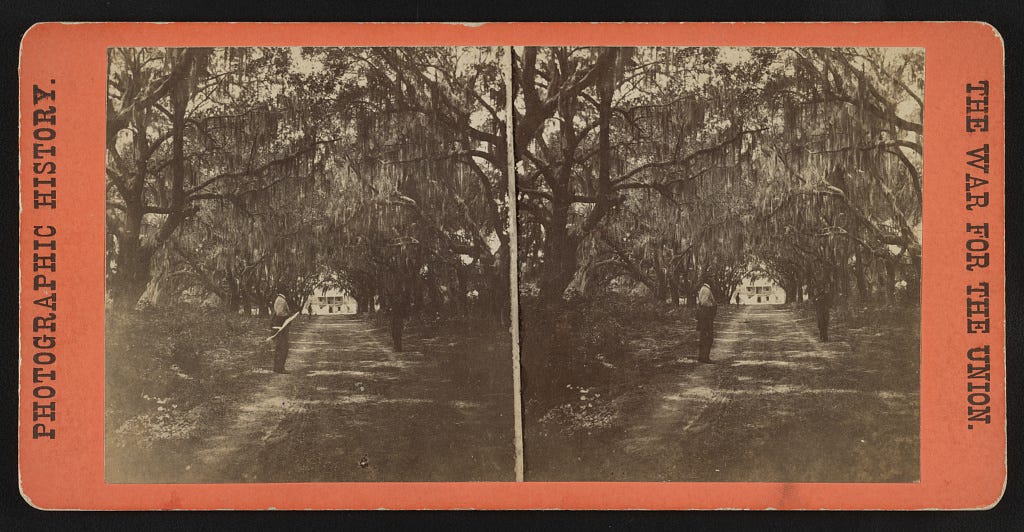

I ducked into the alley of oaks that led to the smoldering ruins of Pleasant Grove Plantation. The storehouses had burned like matchbooks when we lit them, but the trees stood solid and reserved, reaching out across the grass to form an archway that felt cool, damp, and sheltered from the wandering flames.

Up ahead stood the great plantation house, or what was left of it: A cratered brickwork foundation, mighty columns that our men had knocked down like bowling pins, a splintered veranda, shattered windows in a half-collapsed facade, and a deep expanse of black smoking rubble terminating at the base of a solitary red chimney that reached for the treeline.

It was the first time since enlisting in the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery Regiment that I’d seen a plantation house up close, and I was sick with curiosity. Tucking my rifle against my neck, I looked up and down the pathway and saw I was alone. My orders were to round up survivors, but we all knew there were none. At every stop along the Combahee River during the raid today, it was the same story: The planters and their families went running, the Confederate soldiers pissed their pants and retreated before we could fire on their positions, and the slaves came running to the gunboats singing in a language strange to my ears.

Despite all the wreckage, the edges of the plantation house ruins were still hemmed in with greenery, almost strangled by it, as if the plants had all grown a foot since the men of Company C had burned the place to the ground. I could still see how, before we had come to this place, someone had taken a lot of care to train Virginia creeper and yellow jessamine vines to spiral around the exterior banisters and porch railings. Along the perimeter grew camellias, azaleas, and hydrangeas in shades of white to blush to royal indigo, still standing bright beside the void of ash and creosote.

As I walked past the plantation house rubble, I saw there was a wildness to the romantic garden out back, draped in ivy and wisteria as if it had either been overrun or allowed to return to some state of imagined Edenic glory. These southern dandies and their notions. It all made me think of my half brother Pierre who lived in “Chaaaahhhlston.” On the two occasions he’d ever paid a visit to us in Providence, he liked to tell stories about his debauched life among the liquor-swilling, pistol-dueling, syphilitic and insane high society set down in Charleston. I’d never known Pierre well, and I had no way of knowing whether the stories were a front or if his life in Carolina’s great city of Gomorrah really was that charmed.

Back on the river now, I heard the gunship blow its whistle again, a signal to the poor people working in the rice fields that it was safe to run to freedom. I walked on, figuring I had a few moments before anyone noticed I was missing. I put a little swagger in my step as I followed a path to the slave quarters. Giddy under the influence of smoke and gunpowder, I allowed myself to feel like a prince on his estate. A perverse thought crossed my mind: What if Pleasant Grove Plantation could be all mine? What if I stayed and lived the easygoing planter’s life Pierre had described in such vivid purple prose? I let the thought linger.

The slave cabins were emptied out. The people who lived here had taken their worldly belongings in hand at a dead sprint and left very little behind but rough bunks and cornhusks. Back home in Providence I had never met a black man slave or free, and I always assumed the stories about brutality on these plantations were exaggerated to sell newspapers and sentimental novels. Now I saw and knew otherwise. I’d heard stories from the freedmen in Port Royal. I’d seen how they were made to live and die under threat of the whip. And yet I still wasn’t convinced it was any of my concern.

A few paces from the cabins stood a little chapel, still mostly intact except that a cross had been torn from its signpost and planted upside down in a muddy corner of the courtyard. As I drew closer I saw the grass was tamped down, as if there’d been an assembly or a rifle drill. Nearby sat a bristling pile of rice field implements: hammers and hoes and rakes and scythes. Every blunt handle had been sharpened like a pike for battle.

I shrugged at the arsenal — they hadn’t needed to stage a rebellion after all. Still carrying my rifle on my shoulder, I sauntered over to the chapel steps and saw the double doors were ajar. I stepped inside and promised myself this would be the last stop on my tour before heading back to the gunboat.

It was the shabbiest church I’d ever been in, lit only by sunlight that passed through chinks in the walls and raked the pine pews. I saw a little communion table up front, but no Bibles, no hymnals, nothing written down. As my eyes adjusted to the gloom, I noticed something stirring in a pew near the altar.

It was a man, half-reclined in a dark pool with his head propped up on the armrest. His legs hung uselessly to the ground in fine cotton breeches with the cleanest leather shoes I’d seen all year. Everything above the legs was ruined.

The stomach was ripped open in multiple places, with a dark mass writhing and glistening through the tatters of a linen shirt. In one hand was a ledger book, in the other was the barrel of a rifle, pointed toward the abdomen. His supple, hairless face was so pale it faintly glowed.

The man opened his mouth to say something that came out animalistic and choked. I dropped my rifle in the pew and knelt beside him to listen.

“Welcome … to my old Carolina home,” he said. I nodded dumbly. I didn’t have gauze for his wounds and wouldn’t know how to wrap them if I did.

The man continued: “They wouldn’t listen to the gospel. They never learned contentment. They went off searching for a new gospel that would set them fr–”

Thunder clapped in the church and when I opened my eyes again I saw my service rifle was back in my hands, a final round fired into the gentleman’s guts. He wasn’t talking anymore.

I snatched the ledger book from the master’s baby-soft hand and tucked it inside my waistband. I eyed his shoes for a moment before thinking better of it. I turned on a heel, calm as could be, and headed out the door.

I didn’t know what I wanted. As I paced the courtyard I was indulging in the fantasy again, the daydream of strutting down that alley of oaks in a clean linen suit and a broad-brimmed hat, surveying my domain. This land could be mine forever. I didn’t know how, but I felt it could be mine forever.

Out on the river, the steam whistle sounded three times and a great cry went up from the riverbank. General Tubman, as we’d been instructed to call her, gave a song that rang out clear across the water:

”Of all the whole creation in the east or in the west

The glorious Yankee nation is the greatest and the best”

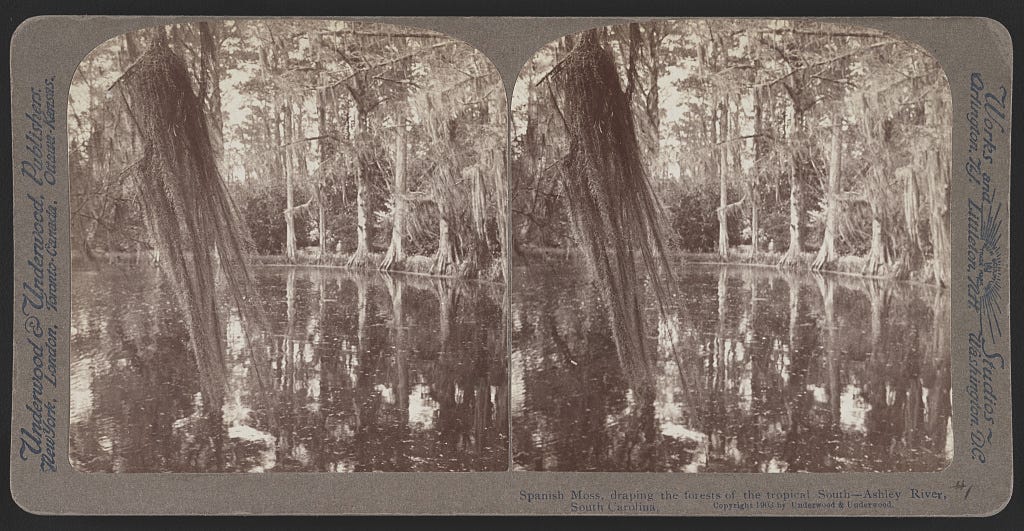

I was humming along now as my hands worked their way along the low-slung branches of a live oak that had breached the courtyard fence. My hands were picking up great skeins of curly gray spanish moss and wrapping them around my head to form a champion’s laurel. The song went on:

“Come along! Come along! don't be alarmed

Uncle Sam is rich enough to give you all a farm."

The freedmen on the shore joined in, and I couldn’t make out the words anymore. Suddenly I was dancing a jig. I never danced jigs. Who had I become? I decided the song was for me.

I closed my eyes as my legs worked and saw a vision of my future on Pleasant Grove Plantation. I saw myself as a devotee of pleasure, enjoying the reward of my gallant deeds in the war, with a wife and children at my feet, and loyal servants at my side. I was dancing without feeling my legs now, and when the song ended and I opened my eyes, all I saw was the clear blue sky framed by the edges of the deep dark woods.

I discovered I was on my back, and my legs wouldn’t move. I tried my arms and they felt like lead. I tucked my chin into my chest and saw something new had sprouted from my belly. It was a jagged wooden pike, pointed at the sky.

My eyes were clear and I felt heat spreading out from my chest. I felt a graceful breeze lift a wisp of my hair, and in the same moment I felt the arm of a live oak cradling my back. Resurrection ferns unfurled along the branch, then turned a deeper shade of green like after a summer storm, then reached for my body until they flicked at my arm hairs.

Carolina jessamine vines caressed my legs and climbed my abdomen, then burst forth in blazing yellow blooms that smelled like my favorite girl’s perfume. The scent made me retch. Shoots of Virginia creeper wrapped themselves gently around my chest, then pulled me tight like a dance partner, then tighter like a hostage. Something cracked in me and I cried out in terror.

In time all of my senses left me except for sight and touch. I saw generations pass. I felt the forest move and burn and grow again. New creeping vines came up through my body and meandered out in various directions toward the chapel, the cabins, and the ruins of the master’s house.

Sharecroppers moved in, worked the land, and died. The fields lay fallow and the woods advanced on me. Tender shoots split me open in the spring, bore fruit, and retreated into the earth when the days grew cold, only to split me open again.

Today, for the first time in ages, I felt a new sensation pierce my chest. It was a wooden stake, and on that stake was a neat white sign:

“For Sale. 40 Acres. Own a Piece of History!”

***

Relatedly, an editor from Jacobin magazine reached out last month asking permission to republish my essay on the brief but deep friendship of John Brown and Harriet Tubman. You can read it here at jacobin.com, or you can read the original with footnotes in the Brutal South archives. Combahee Ferry helped inspire the setting of Pleasant Grove.

I read two life-giving things online this week. One is a short story by my friend Nathan Poole called “Idlewild,” which was recently published in The Common. Heads up: It deals with the death of a child. I’ve admired Nate’s work since we met in college, and I am awed by the level of care and tenderness in each new piece he writes — especially when he deals with churches, large trees, masculinities, and the fabric of family life.

The other piece is Jordana Cepelewicz’s Quanta magazine profile of the mathematician June Huh, who just won a Fields Medal for his work in combinatorics and geometry. Some of my favorite people are mathematicians, and I’m grateful to anyone who can explain their world to me.

If you would like to read more fiction from me, here are a few pieces online:

“Possum Island” (audio edition)

“Charity” (audio edition) - for subscribers only

Brutal South is a free weekly newsletter about class struggle, education, parenting, and religion in the American South. It’s written by me, Paul Bowers, a dad and former local news reporter. If you would like to support my work and get access to the complete archives plus some cool stickers I’ll send you in the mail, paid subscriptions are $5/month.

Bookshop // Twitter // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts