For nearly a week in June 2009, South Carolina Gov. Mark Sanford disappeared. The official story from the governor’s office was that he was hiking on the Appalachian Trail, but no one including state security and the lieutenant governor could get him on the phone. It was a fishy alibi, but that was all we had to go on at first.

I was working as an unpaid intern at the daily paper in Charleston that summer, and looking back, I can say that they got more than their money’s worth out of me. One day nearly a week into the governor’s vanishing act, an assignment editor shooed me out the door at midday with instructions to ask people what they thought about the governor’s absence and report back with a story by 4 p.m.

It was a classic “man-on-the-street” story. I started walking down King Street in my too-small khakis and too-big dress shirt, but the sun was scorching and nobody was hanging out on the sidewalks. I ducked into a bar.

"I'm not a huge Sanford supporter," the bartender Kevin Young told me in the dank half-light of AC’s Bar & Grill, "but I almost feel bad for him on a personal level because it sounds like something I might do."

I hoofed it a few more blocks and stepped into Bubba Slye’s Deli, where I noticed the entire late-lunch crowd was silent and staring at the TV in the corner.

While I had been wandering around pointing my voice recorder at passing strangers, another reporter (Gina Smith at The State) had found the governor sneaking back into the country at the Atlanta airport and confronted him about it. Now he was on national news behind a bank of microphones, sobbing as he confessed that he had been in Argentina visiting his “soul mate,” a woman who was not his wife.

The man-on-the-street quotes turned scornful after the press conference: The governor was a liar, a cheater, an embarrassment to the state. With 10 column-inches’ worth in my notebook, I power-walked back up King Street to the newspaper office, where the atmosphere was Peak Newspaper. Veteran newshounds cracked jokes in poor taste, political reporters juggled phones, and editors scrambled to rearrange the next day’s front page. I was thrilled to be part of the machine for a day.

Sometime shortly after that — the next day, or maybe two days later — an editor told me to drive out to Sullivan’s Island, where the Sanford family home was, to see if First Lady Jenny Sanford wanted to give a comment about her husband’s adultery. She hadn’t spoken publicly on the matter, and for some reason they wanted the intern to prod her about it.

I had my reservations about going. The governor’s disappearance was newsworthy, but nagging his wife about their love life felt prurient and needlessly invasive. I ignored my better instincts and drove across two bridges to the address the editor had given me.

The Sanfords had a big dog who didn’t seem pleased as I walked up the driveway and onto the veranda of the grand beach mansion. I knocked on the door and hoped no one would answer.

To my surprise, Jenny Sanford opened the door. I had a press badge on; she knew what I was there for.

I mumbled an introduction and asked if she wanted to comment on her husband’s affair. Her expression was either withering or pitying, I can’t say for sure, but she politely told me she was busy making lunch and would rather not comment.

My contribution to the news that day was a curt sentence in someone else’s article, something to the effect of “Jenny Sanford declined to comment.”

If an internship is supposed to be an educational experience, then I suppose I learned something that day about the hollow morality of “just following orders.” But I also did about 8 hours’ worth of free labor, just like every weekday that summer after my sophomore year of college.

***

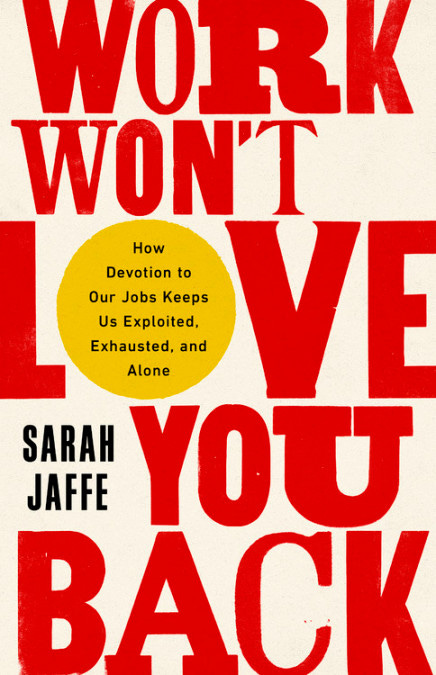

I was thinking about my unpaid summer internship at the Post and Courier recently as I read Sarah Jaffe’s phenomenal book Work Won’t Love You Back: How Devotion to Our Jobs Keeps Us Exploited, Exhausted, and Alone.

The book is a labor history, told via deep research and intensive interviews with workers in a variety of industries where bosses preach some variation of the capitalist doctrine, “Do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life.” There are chapters on teachers, domestic workers, nonprofit employees, athletes, and so on.

A common thread in most of the chapters is that women’s labor, and labor that has historically been dubbed “women’s work,” either gets discounted or erased entirely as a “labor of love,” rather than a career path worthy of liveable compensation. Some work, like the labor of artists, gets shunted off into the category of “genius,” which also somehow sits outside the normal rules of compensation.

The 7th chapter is about interns. Jaffe writes:

What really defines the intern, after all, is hope. Communications scholars Kathleen Kuehn and Thomas F. Corrigan coined the term “hope labor” to apply to “un- or under-compensated work carried out in the present, often for experience or exposure, in the hope that future employment opportunities may follow.” Hope labor is a snake eating its own tail, and the intern is the hope laborer par excellence. Working for free in order to one day get one of those jobs that are worth loving, the intern is the vehicle by which the conditions of contingency and subordination that are common to low-wage service work creep into an increasing number of salaried fields. Justified by the meritocratic myth that the best interns will get jobs, the internship actually drives down wages by introducing a new wage floor—free—into the system, allowing companies to substitute interns for entry-level workers. The interns replace the very employees they hope to be.

For the chapter on interns, Jaffe interviewed a woman named Camille Marcoux, who became disenchanted in college while working as an unpaid intern at a nonprofit community organization.

“I feel like they are training us for exploitation,” Marcoux said, and I immediately knew what she meant.

Reading Jaffe’s book, I felt all the familiar sensations that come with reading sharp Marxist analysis of labor and political economy. The lies I’d been told by teachers, pastors, and bosses started to sound ludicrous, and I began to confront the lies I had internalized in order to keep going. The term “hope labor” applied not just to my uncompensated internship, but also to the many unpaid hours I worked off the clock as a full-time reporter.

Looking back on my unpaid internship, I had it good as far as interns go. I was able to stay with my parents for free in the Charleston suburbs all summer, and my generous scholarships even covered the tuition I had to pay for the privilege of working for free. I never had to work a real job to support my passion. For my second summer interning on the news desk in 2010, I even convinced the editors to pay me the equivalent of a starting reporter’s salary. (Sometime after that, the P&C started paying all of its summer interns, following trends in the industry and shifting labor law.)

Unpaid internships were a rite of passage in journalism at the time I attended the J-school at the University of South Carolina. Professors and advisors told us they were a way to get real-world experience and clips that we could attach to resumes when we applied for jobs after graduation. I was fairly oblivious to how that rite of passage kept newsrooms filled with people just like me: straight white folks with no debt and financial support from their families.

This week I dug up an old email I sent to my university’s internship coordinator at the end of my 2009 internship. I was one of 7 students from UofSC interning that summer at the Post and Courier, and I had been tasked with writing some sort of summary for an internal newsletter about it. For some reason I wrote in a detached third-person voice about the whole thing.

I cringed with my entire body as I read the opening paragraph:

It’s a well-known truism in college journalism circles: If you don’t get internships now, you won’t get a job when you graduate. Operating under that mindset, the seven USC students working at the Post and Courier newspaper in Charleston, SC, could have seen their summer 2009 internship experience as little more than a step on the career ladder. But by the summer’s end, they had come to see the downtown office as something between a training center and a proving ground. For some, the pay was meager (read: nonexistent) and the hours were long. The work was unglamorous and often stressful. What they experienced were the daily lives of journalists, free of sugarcoating and mollycoddling.

I thought I was tough. I thought I had grit. But really I was just a sucker.

I never considered how my free labor was depressing wages for working reporters until I found myself on the other side of the equation. After college, I took a job on staff at the alt-weekly in Charleston, making $27,000 a year and pulling 60-hour weeks while a year-round stream of interns did grunt work for free.

I eventually worked for the Post and Courier again, finishing my career in 2019 making $38,000 a year with a stack of pointless journalism awards and a debilitating case of depression and anxiety. I was 30, with 3 kids, making the same salary as first-year public school teachers in my county, and I knew that a fresh-faced college grad would happily come along and replace me for less.

I guess you could say my reserve of hope labor ran out.

***

I can laugh now thinking about the work I did for free. I wrote 1A news stories, shot and edited videos for the website, and even picked up a few night shifts on the crime beat.

Governor Sanford’s love affair was an international news story in the summer of 2009, and one day I remember someone yelling across the newsroom, “Anybody speak Spanish?”

I timidly raised my hand and they handed me the phone. The call was from an Argentine news radio station looking for an American perspective on the scandal, and I fumbled my way through it with my mangled high school Spanish. I frantically tried to remember the Spanish word for “embarrassed,” doing my best to avoid saying the false cognate embarazada (pregnant). Somehow I made it through without causing an international incident.

The flimsy theory behind the unpaid internship was that I was being compensated, but in the form of experience, not money. I earned college credit-hours for completing some paperwork and getting good evaluations from my manager, hence the tuition fees.

I have been thinking about the disciplinary function of internships since reading Work Won’t Love You Back. I underlined this sentence from Chapter 7:

“When one is expected to perform gratitude every day on the job, it makes summoning the mindset necessary to organize for change that much harder.”

I performed gratitude alright. I groveled and thanked my bosses and looked down on people who lacked the means or self-abasement to do that kind of work for free. I don’t want that life for my children, or anybody’s children.

Jaffe’s writing is trenchant and precise, but at the same time profoundly humane. Each chapter is held together by a single worker’s story, recorded in long naturalistic quotes that remind me of Studs Terkel. I found plenty of cause for despair, but it was always counteracted by stories of worker solidarity.

“We want to call work what is work so that eventually we might rediscover what is love,” Silvia Federici wrote, in a quotation that Jaffe used in her conclusion. My work was always work, even when I called it an education or a labor of love.

I don’t love my work anymore, and I doubt I ever will. I don’t think I forgot what love is, but I have more room in my heart for it now.

***

Work Won’t Love You Back is available to order via the Brutal South Bookshop page.

If you liked today’s newsletter, you might appreciate this one about depression in the newsroom or this one about Mark Sanford’s tragicomic 2020 presidential campaign.

Brutal South is a free weekly newsletter that publishes every Wednesday. For $5 a month, you can support my work and get some exclusive stuff, including cool vinyl stickers and an original 37-minute audio novella that I wrote, recorded, and soundtracked. If you’re interested, click here to see the running list of perks or hit the Subscribe Now button below.

Twitter // Bookshop // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts

My first internship experiences were with nonprofits and with every job I thought-- this is something a full-time person should be paid to do.

Eerie timing, I was just thinking about my own experiences interning at the Post & Courier back in the summer of 2010. I can very distinctly recall listening to a call-in show on NPR on my way to or from work about whether interns should be paid for their labor and at that moment I started to realize the value of my work. I had my photos printed full color, front page, above the fold that summer. And I was constantly crossing my fingers that I wouldn't overdraft my debit card trying to buy lunch. There was sometimes very little thought given to the assignments I was put on either. Like when I was sent out on a boat offshore near Beaufort to photograph artificial reefs being installed and lost my breakfast over the side because I did not plan to get violently seasick when I went to work that day. After I graduated, I begged for a job there so I wouldn't have to leave Charleston. Still waiting to hear back on that position 9 years later.