I don’t think I had a choice of subject matter for the newsletter this week. Brutalism was in the news.

As you may have seen, the Trump administration recently drafted an executive order dubbed “Make Federal Buildings Beautiful Again” that would require federal building projects to conform with classical architecture styles reflective of “our national values,” whatever the hell that means.

The draft order obtained by Architectural Record specifically takes aim at projects that were “influenced by Brutalism and Deconstructivism,” such as the U.S. Courthouse in Austin (2012, Mack Scogin Merrill Elam Architects) and the Wilkie D. Ferguson Jr. U.S. Courthouse in Miami (2007, Arquitectonica), saying these buildings have “little aesthetic appeal.”

Measured against the broader cruelties perpetrated by this administration, this is a small matter. There’s a good chance the president will forget all about it by the end of his next TV Time.

But still.

If carried out, this order would reverse existing federal architecture guidelines that state, “Design must flow from the architectural profession to the government and not vice versa.” It would dictate that massive new building projects adopt the aesthetic preferences of 18th-century gentry. The leaked executive order also happens to be red meat for the white nationalist members of Trump’s base, who have been praising the decision on sites like American Renaissance.

I don’t pretend to be an expert, and I don’t have an axe to grind with neoclassical architecture per se. Architectural styles don’t have an inherent politics, but they can serve as proxies in culture wars that our leaders want to wage. (For a deep dive on the theory and politics behind this moment, I’d point you to architecture critic Kate Wagner’s piece “Duncing About Architecture” in The New Republic.)

What follows is a personal story about architecture, the kind of thing I’d start ranting about at a house party after a glass-and-a-half of wine.

***

I picked the name of the Brutal South newsletter on a whim because I thought it sounded cool, then justified the decision to myself after the fact.

The “South” part was self-explanatory: I am a native resident of South Carolina and spent part of my childhood in the Houston suburbs. My worldview has been shaped by the people and geography of the American South.

The “Brutal” part, I rationalized, could work as a triple-entendre:

“Brutal” as in the brutality of oppressive economic and racial structures in American life.

“Brutal” as a positive descriptor of heavy metal music, another topic I figured I’d write about from time to time.

And finally, “brutal” as in brutalist architecture, which draws its name from the French béton brut — that is, raw concrete.

I’m an architecture layman, but I’m a fan of brutalism. My first conscious encounter with a brutalist building was on a 2013 trip to see my brother at UC-San Diego, where I took some time to gawk at architect William Pereira’s brutalist-futurist Geisel Library.

It’s an imposing and improbable-looking structure. Standing outside under the cantilevered upper floors, I felt like I was staring at an inverted pyramid driven into the ground by aliens. Concrete arms held the whole thing aloft at 45-degree angles to the earth, and the enormous plate-glass windows flashed gold, orange, and pink in the California sunset.

With no knowledge of architectural history or philosophy, I experienced the building on a purely emotional level. It felt zany, maybe as an homage to its namesake, Theodor Geisel, a.k.a. Dr. Seuss. It felt audacious and new, particularly as a contrast to the crumbling antebellum architecture of the East Coast city I knew best. What little I knew about postwar modernism and abstract visual art seemed summed up in this weird edifice I’d made a pilgrimage to see.

I have heard from other southerners over the years who gained a similar appreciation for wild modernist styles after growing up in towns that felt like Civil War museums. I have also met Californians who, upon hearing I come from Charleston, express their admiration for “all those beautiful old historic buildings.” Vive la différence, I guess.

Back home in South Carolina, I started noticing the telltale signs of brutalism in buildings that I hadn’t paid much attention to before. I learned that Columbia’s Thurmond Federal Building was a latter-year exemplar of the movement, with its hulking facade, angular window hoods, and tons upon tons of rough, exposed concrete. My first Brutal South entry was an ode to this building.

***

Over the years I learned how architecture reflected my state’s history.

Charleston, where I grew up, has retained a lot of its stately old houses built on wealth from plantations and the slave trade. Part of the reason the historic downtown feels like such a time capsule (and a fantastic tourist attraction to boot) is that the city council established the nation’s first Board of Architectural Review in 1931 to enforce zoning ordinances and strict aesthetic rules in the Old and Historic District. While the city has done an admirable job of preserving buildings, we have usually failed — in signage, in guided tours, and in the general realm of public history — to tell the complete story of the toil, oppression, and violence that went into building Charleston.

The capital city Columbia, on the other hand, lost many of its historic buildings to a massive fire during the U.S. Civil War. Ironically it was Charleston that fired the first shots of the war, but Columbia that bore the brunt of the structural damage. As a result, Columbia residents accepted the construction of modern buildings and skyscrapers as a sign of growth and progress during the 20th century. The downtown University of South Carolina campus, where I spent four years as an undergrad, includes some fantastic examples of brutalist and modern designs by the architectural firm Lyles, Bissett, Carlisle and Wolff. (The architectural historian Dr. Lydia Mattice Brandt, who I interviewed for my first newsletter, worked with her students to produce some fascinating documentation on those buildings if you’re interested.)

Working as a newspaper reporter in Charleston for the last eight years, I sat through my fair share of meetings of the Board of Architectural Review. The most interesting fight I ever witnessed was about a clash between modern and neoclassical styles.

Clemson University wanted to build a new home for its satellite architecture school in Charleston, and they hired the Oregon-based architect Brad Cloepfil in 2012 to help draw up a proposal. He proposed a boxy three-story building with huge plate glass windows shielded by wavy, white concrete screens.

Initial reactions were mixed. Whitney Powers, a local architect, praised “the control and celebration of daylight, the use of horticulture in a temperate climate, the texture of urban streetscapes, and the day's prevailing construction technologies.”

On the other hand, one attendee at a BAR meeting said the building looked like a Martian Walmart. The acting BAR chairman said the proposal “[fell] short in harmony” with the historic buildings surrounding it.

After one of the more contentious BAR meetings about the Clemson proposal, a white-haired gentleman in a tweed flat cap tracked me down in the lobby and gave me a hand-drawn blueprint of his own alternate proposal. All I remember is it had columns and would definitely fit the mold of a “neoclassical” building. He said he was an architect, and I’m sure his design had some merit. Personally I found it intensely boring, but what do I know?

I interviewed Cloepfil about the proposal. Of course I asked him about the concrete. He said this:

I think people have been abused by concrete buildings in the past. Concrete is one of the most durable — it's no different than stone or brick ...

You know, I think a lot of the reaction — and this is kind of philosophical here, dangerous turf — a lot of people's reaction to contemporary architecture is because they've seen bad contemporary architecture. And so I think architects have dug their own hole to a certain extent. I think once people see things that are more responsive and thoughtful and particular to place, and hopefully beautiful, then people start to get attached to it. That's certainly been my experience. When you do contemporary work, whether it's Charleston or other cities, people are nervous about it. They haven't seen it before. But once it's built, they usually fall in love with it.

A year after Cloepfil’s designs first went public, the BAR simply failed to act on the proposal. Three of the six members present at an October 2013 meeting recused themselves at the last minute citing conflicts of interest. Cloepfil, who had flown in from Portland for the meeting, had a good sense of humor about the whole thing and promised to keep working with the city on the proposal.

The building was never built. The architecture center moved into a renovated cigar factory instead.

***

I keep thinking about what Cloepfil said, about how people had been “abused” by concrete architecture.

In the context of our interview, he was talking about concrete-heavy structures that had weathered poorly, often due to poor design or a lack of maintenance by austerity-starved governments. From the decay of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis to the deadly Grenfell Tower fire in London, there are plenty of examples to draw on.

People were abused by neoclassical architecture too. Southerners have only started to unwrap the romantic gauze surrounding plantation homes, raising questions about the ethics of hosting weddings on former slave labor camps.

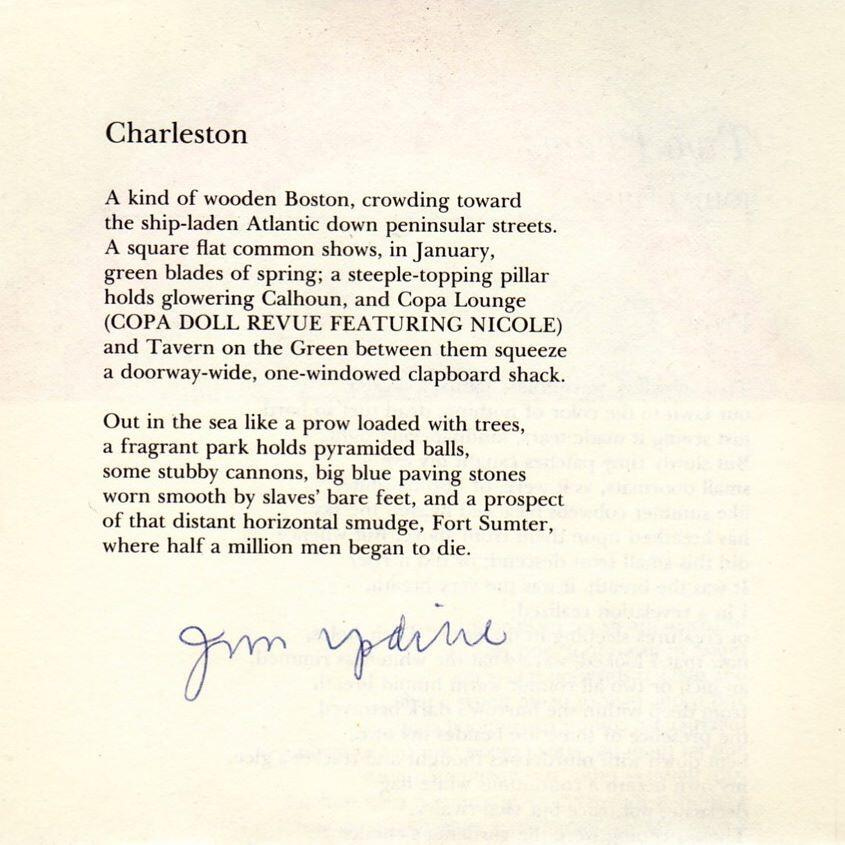

Sometimes when I’m walking in downtown Charleston, if I start to feel too wistful about the fanciful colors of Rainbow Row or the regal verandas of some South of Broad mansion, I think about a poem John Updike wrote about the city in 1988.

These structures were built in the fashion of their time, according to the fads of the city. I don’t fault the designs themselves. Some of them are genuinely beautiful to me.

But if I look closely enough, if I linger long enough, I remember where these buildings came from. They were built as ostentatious displays of ill-gotten wealth. From the slave kitchens to the gaudy parlors, form followed function after all.

I would have liked a new building to present some contrast, to hint at the future. I would like that for any city.

***

The photo of the Geisel Library is by Wikimedia Commons user Ray_from_LA, shared via a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

New to the Brutal South? Check out the archives, including my previous piece on Marcel Breuer’s Thurmond Federal Building in Columbia.

You can subscribe to the Brutal South newsletter for free to get something new in your inbox every Wednesday (I promise it’s not exclusively about brutalist architecture). If you’re a fan, consider sharing the newsletter with your friends or becoming a supporter for $5 a month.