Censors lose in the end

The speech police want to ban Ta-Nehisi Coates. We’ve got them outnumbered.

A most predictable outcome has arisen in South Carolina. After passing a gag order to stop the imaginary threat of “critical race theory” in schools, the state has purged a memoir about American racism from the syllabus in a high school classroom.

An outcome such as this was the obvious purpose of the teacher censorship provisos that Republican lawmakers slipped into the last two years’ state budgets, which forbid public school teachers from teaching that “an individual should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his race or sex,” along with a long list of other vague speech prohibitions.1

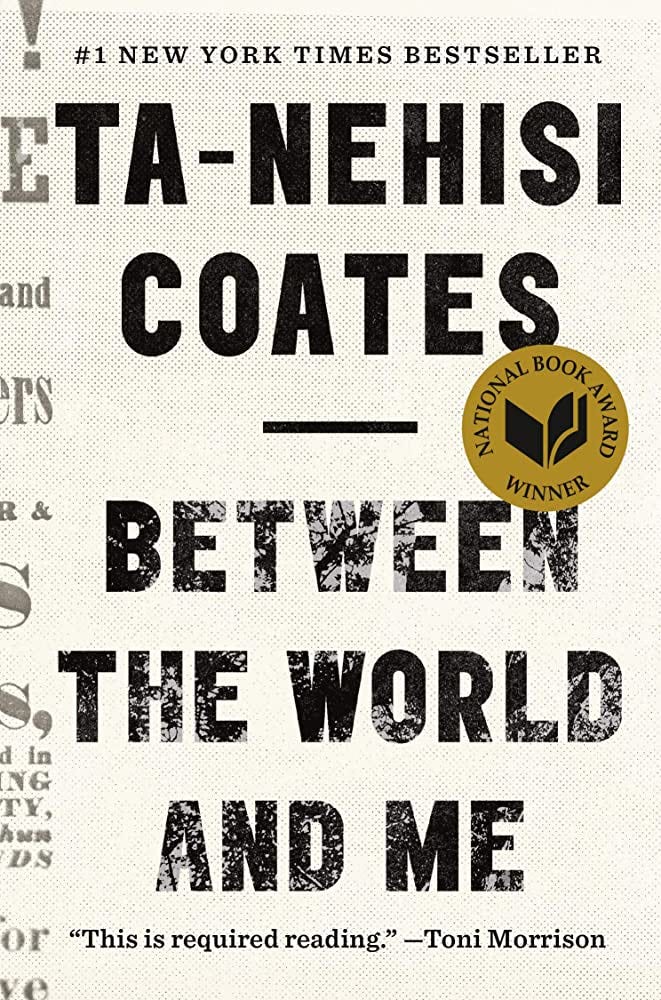

Bristow Marchant, a reporter at The State newspaper, reported on Monday that in the spring of 2022, students in an Advanced Placement Language and Composition class at Chapin High School complained to the Lexington-Richland 5 School Board after being assigned Ta-Nehisi Coates’ 2015 bestseller Between the World and Me.

“I am pretty sure a teacher talking about systemic racism is illegal in South Carolina,” one student wrote.

To be clear, it is not illegal for teachers to talk about systemic racism in South Carolina. But in a season of unhinged school board rants by the Moms for Liberty network, vague condemnations of “critical race theory” by the state education superintendent, micromanagement of classroom materials by the governor himself, and frivolous lawsuits filed by the all-white South Carolina Freedom Caucus alleging anti-white bias in schools, the unofficial state policy is to intimidate teachers into silence regardless of what the law says.

Not another CRT panic

In the weeks after South Carolina Superintendent of Education Molly Spearman put out a statement condemning “critical race th…

In this case, a school principal caved to pressure and censored the book. The school board caved too. If recent history is any indicator, we can expect The College Board to cave, as they did in Florida when Gov. Ron DeSantis and his allies demanded a whitewashing of the AP African American Studies curriculum. (Coates’ writing was removed there, too.)

Here in South Carolina, the teacher was left standing up for herself, writing to her district superintendent with a spirited defense of the book’s inclusion in a unit on persuasive essays. Her courage is an inspiration. We can’t abandon her to the mob.

Book bans remain massively unpopular in the United States. In a poll conducted last year by the EveryLibrary Institute, just 18% of respondents said they supported banning books on issues of race and “critical race theory.” A small, entitled minority doesn’t get veto power over what the rest of our children learn. This is a message we can take to every school board, library board, and county council where the censors choose to wield their influence.

It can be daunting to stand up to the intimidation tactics of groups like Moms for Liberty, who got their start harassing and threatening their neighbors in Florida school districts. The piles of dark money behind these groups and others like the State Freedom Caucus Network can make them seem larger and more powerful than they really are. But never forget that we outnumber them.

Ta-Nehisi Coates is a literary giant who doesn’t need someone like me to defend his bona fides, but I’ll say this anyway: The politicians who seek to ban his work are revealing a lot about themselves. Coates wrote this to his then-14-year-old son in Between the World and Me:

[M]y experience has been that the people who believe themselves to be white are obsessed with the politics of personal exoneration … Considering segregationist senator Strom Thurmond, Richard Nixon concluded, “Strom is no racist.” There are no racists in America, or at least none that the people who need to be white know personally.

In some ways, Between the World and Me was a product of its time: Coates referred early in his book to the police murders of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, and Tamir Rice, and to the nascent uprisings of 2014. In South Carolina in 2015, when we witnessed the white supremacist massacre at Emanuel AME Church and the North Charleston Police murder of Walter Scott, I turned to Coates’ writing to understand the moment. He wasn’t a voice of hope, but of commitment and struggle.

Coates’ work fits into a long tradition. The title Between the World and Me comes from a 1957 Richard Wright poem, and the format of the book echoes James Baldwin’s 1962 classic letter to his own young nephew, The Fire Next Time — which took its title from an old spiritual song, which in turn was inspired by Jesus’ teachings and Noah’s story in the book of Genesis.

A decision to censor Coates, like Wright or Baldwin in previous generations, is an attempt to excise a modern classic from the canon. It is also a decision to privilege the comfort of white Americans (or “people who need to be white,” to borrow Coates’ phrase) above all others. To quote Coates from an interview earlier this year:

We’re uncomfortable every day. Being Black is to be existentially uncomfortable. Being a woman is to be existentially uncomfortable. Being LGBTQ is to be — being trans is to be uncomfortable. That is the nature of human beings. It’s the nature of the human experience, and particularly, as I said, for those who live outside of the mainstream. People who simply seek comfort, and people who come to education of all things to seek comfort, don’t make for good citizens, and they don’t really make for mature adults, honestly.

Jeremy C. Young, director of PEN America’s Freedom to Learn Program, wrote yesterday that the removal of Coates’ book at Chapin High School is an example of “outrageous government censorship.” It is. South Carolina educators and historians have been sounding the alarm about this wave of censorship for more than two years now.

Here, for example, is what the South Carolina African American Heritage Commission wrote to then-State Superintendent Molly Spearman on June 24, 2021, after she came out in favor of a vague ban on “critical race theory”:

Undeniably, slavery, Jim Crow, and systematic racism are all a part of our history, and they continue to impact our society today. We must present our history as it occurred, not how certain groups wish it had been. Addressing difficult lessons from the past, allows us to better understand and educate students in the present while avoiding making similar mistakes in the future.

To date, curriculum censors in the South Carolina General Assembly have only managed to enact their will via year-by-year provisos that they slip into the budget without much discussion. They attempted to make this provisional gag order permanent this year with House Bill 3728, a teacher censorship bill that they called the “Transparency and Integrity in Education Act.” I traveled to Columbia in March to testify against this bill, as did dozens of others. Nobody in the subcommittee meeting that day spoke in favor of this senseless, odious bill.

Three minutes and the truth

Before sunrise Wednesday morning, I kissed my wife and kids goodbye and began driving halfway across South Carolina. I had taken the day off work and made arrangements with my family. For the first time in my life, I was going to testify in front of state legislators in Columbia.

Thanks in part to intra-party beef between mainstream Republican lawmakers and the marginally more extremist South Carolina Freedom Caucus, the bill’s sponsors didn’t manage to pass a version of the bill that reconciled the House and Senate amendments this year. They’ll have another chance to ram the bill through when the legislative session continues in 2024.

We can kill this bill in the Statehouse, or we can kill it in the courts later on straightforward First Amendment grounds. However we win, we need to do it loudly and publicly, in overwhelming displays of solidarity with teachers like the one who stuck her neck out at Chapin High School. We’ve got the numbers. We’ve got the truth.

***

Brutal South is a free weekly newsletter about class struggle and education in the American South.

Bookshop // Twitter // Bandcamp // Spotify Podcasts // Apple Podcasts

The proviso is labeled “Partisanship Curriculum” in the last two years’ budgets. See Proviso 1.93 in the 2022-2023 Appropriation Act and Proviso 1.105 in the 2021-2022 Appropriation Act.

As a professor of Southern and African American studies, I am angry and sick at heart but not surprised at the state lege’s actions. I testified against last year’s slate of Don’t-Say-Gay laws and the smugness, arrogance, and condescension of the people gleefully wrecking our bottom-tier education system as some kind of moral crusade has to be seen to be believed. I don’t know how, if systemic racism doesn’t exist, they explain their own dynamic: a virtually all-white ruling cartel ignoring and taunting a virtually all black minority party (that actually represents majority state interests) amid a mortuary landscape of monuments to unjust wars, slavers, and segregationists. It seems anyone with an ounce of self-awareness would feel shame. But the statehouse is filled people who need to be white/right. And the supermajority of power they have built while people who knew better slept has me terrified for my grandchildren’s future.