You'll never un-see it

Photographs of the dead can shock or numb us. What matters is the action we take.

Note: This piece includes graphic discussion of war, violence, and injury.

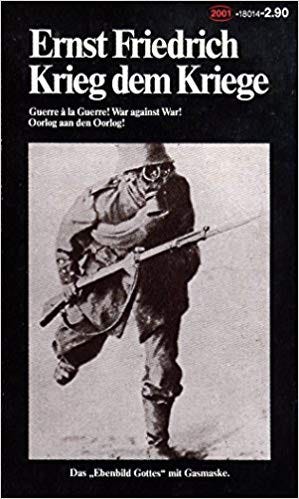

Six years after the First World War, the German pacifist Ernst Friedrich tried to end all wars forever. His weapon was photography.

“Krieg dem Kriege!” declared the cover of his 1924 book — “War Against War!”

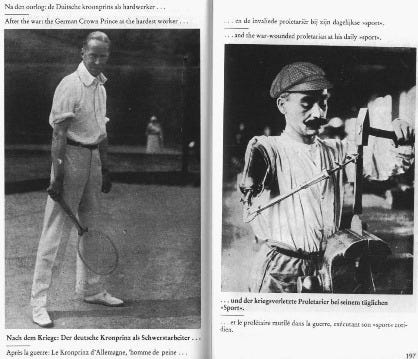

The book was a photo essay, starting with images of children’s war toys and ending with images of soldiers’ graves. In between, he arranged a series of battlefield photos, some of which had been censored during the war.

Horses and men trapped in barbed wire. Naked bodies dusted with snow in some anonymous ditch. A dead priest hanging from a noose, face toward the lens. Shirtless starving Armenian children lying down in dirt.

(A scan of the whole book is available online, but be advised that the images are extremely graphic and upsetting.)

The poets had already tried to strip war of its glory, particularly those like Wilfred Owen who had swallowed smoke and tasted mustard gas in the trenches. They were already losing the battle when Friedrich fired his opening salvo.

His book began with an introduction, translated into four European languages, decrying the weakness of the written word:

But all the treasury of words of all men of all lands suffices not, in the present and in the future, to paint correctly this butchery of human beings.

Here, however, in the present book, — partly by accident, partly intentionally — a picture of War, objectively true and faithful to nature, has been photographically recorded for all time.

And it’s true, the written word has limitations. So does photography. Friedrich tried to wed their strengths, writing scathing captions for each photo. In many cases he sarcastically juxtaposed a gruesome photograph with a war hawk’s cheery cry to arms.

Above a photograph of a human skull with a helmet perched on top, he quoted Kaiser Wilhelm II: “I lead you towards glorious times.” Above a close-up of a young soldier’s face with the right cheek torn off, teeth visible and lips sagging, a quote from Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg: “War agrees with me like a stay at a health resort.”

In 1925, Friedrich opened an Anti-War Museum in Berlin, continuing his crusade to end all wars. The Nazis shut it down in 1933 and destroyed his entire collection.

I first heard about Friedrich’s anti-war photo project in Susan Sontag’s book Regarding the Pain of Others, which she wrote in part to account for her own changes of belief since publishing 1977’s On Photography.

Late in life, Sontag grew ambivalent about the capacity of photographs to either numb the senses or catalyze action. She wrote:

Since On Photography, many critics have suggested that the excruciations of war — thanks to television — have devolved into a nightly banality. Flooded with images of the sort that once used to shock and arouse indignation, we are losing our capacity to react. Compassion, stretched to its limits, is going numb. So runs the familiar diagnosis. But what is really being asked for here? That images of carnage be cut back to, say, once a week? More generally, that we work toward what I called for in On Photography: an "ecology of images"? There isn't going to be an ecology of images. No Committee of Guardians is going to ration horror, to keep fresh its ability to shock. And the horrors themselves are not going to abate.

***

There are some images you have seen, and images yet to come, that will never leave your mind. Thanks to free mass distribution, you can’t avoid seeing them unless you really try.

Last week the photojournalist Julia Le Duc captured one of those images. Amid a crisis fueled by the extraordinary cruelty of immigration policies in the U.S., Le Duc found the body of Salvadoran migrant Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez face down in the Rio Grande. His 23-month-old daughter Angie Valeria, also dead, was tucked into the back of his shirt with her arm wrapped around his shoulder. They had washed up in a morass of reeds and trash.

The photograph ran in the Mexican newspaper La Jornada and soon spread worldwide. It brought an incomprehensibly vast humanitarian disaster into focus, like Nilüfer Demir’s 2015 photograph of three-year-old refugee Alan Kurdi washed up dead on a Mediterranean beach in Turkey.

We all felt something when we saw the photo from the Rio Grande. I read how the father had crossed the river with his daughter on his back, dropped her on the shore, and started swimming back to retrieve his wife. The daughter, alone on the riverbank, tried to follow her dad back into the river, and they both were caught in a current and drowned.

The girl was only a few months younger than my son. I imagine he would have done the same thing as that little girl, frightened and alone with his only source of worldly security floating away. Looking at the photo, I can feel my daughter’s wet arm wrapped around my neck at the swimming pool when she was that size.

These photographs — a Syrian boy drowned in the Mediterranean, a starving Sudanese girl with a vulture perched behind her, and on and on — what did they inspire? For some viewers, philanthropy. For a brave few, rescue boats and personal sacrifice to save lives.

They did not end the systems that grind these bodies down.

Systems produce the results they are designed to produce, and in the case of U.S. immigration enforcement, it’s a system that kills children and separates families. U.S. Customs and Border Protection has been consistently throttling asylum requests at legal ports of entry, in some cases forcing families to stay in overflowing camps south of the border where cartels have been known to kidnap people. The current administration has been trying to narrow the qualifications for asylum, excluding, for example, survivors of domestic and gang violence (a judge rejected that change, for now).

It’s a system that encourages acts of desperation, like swimming across a river with a child on your back. Two hundred eighty-three migrants died en route to the U.S. last year by one estimate. From the Associated Press:

In recent weeks alone, two babies, a toddler and a woman were found dead in the sweltering heat. Three children and an adult from Honduras died in April after their raft capsized on the Rio Grande, and a 6-year-old from India was found dead earlier this month in Arizona, where temperatures routinely soar well above 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

People who want their neighbors to die are not likely to be swayed by photographs of the dead, no matter how gruesome or affecting.

For those of us who want migrants to live, photographs like this one can inspire action — or despair.

***

Julia Le Duc was right to take that photograph, and La Jornada was right to publish it. The story must be told. Journalists can’t operate with utilitarian ethics; integrity is the only standard.

Le Duc explained her photograph in The Guardian:

You get numb to it, but when you see something like this it re-sensitizes you. You could see that the father had put her inside his T-shirt so the current wouldn’t pull her away.

He died trying to save his daughter’s life.

Will it change anything? It should. These families have nothing, and they are risking everything for a better life. If scenes like this don’t make us think again — if they don’t move our decision-makers — then our society is in a bad way.”

The phrase “It should” strikes a deep chord with me. The work of journalists is often a prayer for change. Sometimes prayers go unanswered.

Sontag, again:

Compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers. The question is what to do with the feelings that have been aroused, the knowledge that has been communicated. If one feels that there is nothing "we" can do — but who is that "we"? — and nothing "they" can do either — and who are "they"? — then one starts to get bored, cynical, apathetic.

And it is not necessarily better to be moved. Sentimentality, notoriously, is entirely compatible with a taste for brutality and worse … The imaginary proximity to the suffering inflicted on others that is granted by images suggests a link between the faraway sufferers—seen close-up on the television screen— and the privileged viewer that is simply untrue, that is yet one more mystification of our real relations to power. So far as we feel sympathy, we feel we are not accomplices to what caused the suffering. Our sympathy proclaims our innocence as well as our impotence.

***

I’ve been to Matamoros, the border city where Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his daughter attempted to cross the Rio Grande. I was a teenager; it was one of those house-building mission trips that serves as a rite of passage for many evangelical church youth groups north of the border.

I could tell you what I saw. I could show you the pixelated pictures I took on my early-2000s digital camera. Hospitable people, miserable poverty, whole neighborhoods where kids picked scrap from garbage dumps.

Would it matter if I showed you that? Would it change your beliefs or actions?

It is up to us, the viewers, to decide what we do with Le Duc’s image. Depictions of suffering can be propagandized in any direction, including toward revenge, war, and fascism. May we all be moved, not to pity, but to action.

Consider what action you are willing to take. The July 12 nationwide vigil against migrant concentration camps is a start. The Texas Tribune has compiled a list of organizations seeking to help migrants at the border.

If you feel despair creeping in, stop looking at the images for a while. Wait until you feel you are able to do something. Compassion saves no one.

The bodies of Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his daughter were returned to El Salvador to be buried in a private ceremony Monday. They were buried in San Salvador in a section of a cemetery named for Saint Óscar Romero, according to The Guardian.

As for Ernst Friedrich, he never won his war against war, but his mission continues. The Anti-War Museum re-opened in Berlin in 1982, fifteen years after its founder’s death. Admission is free.