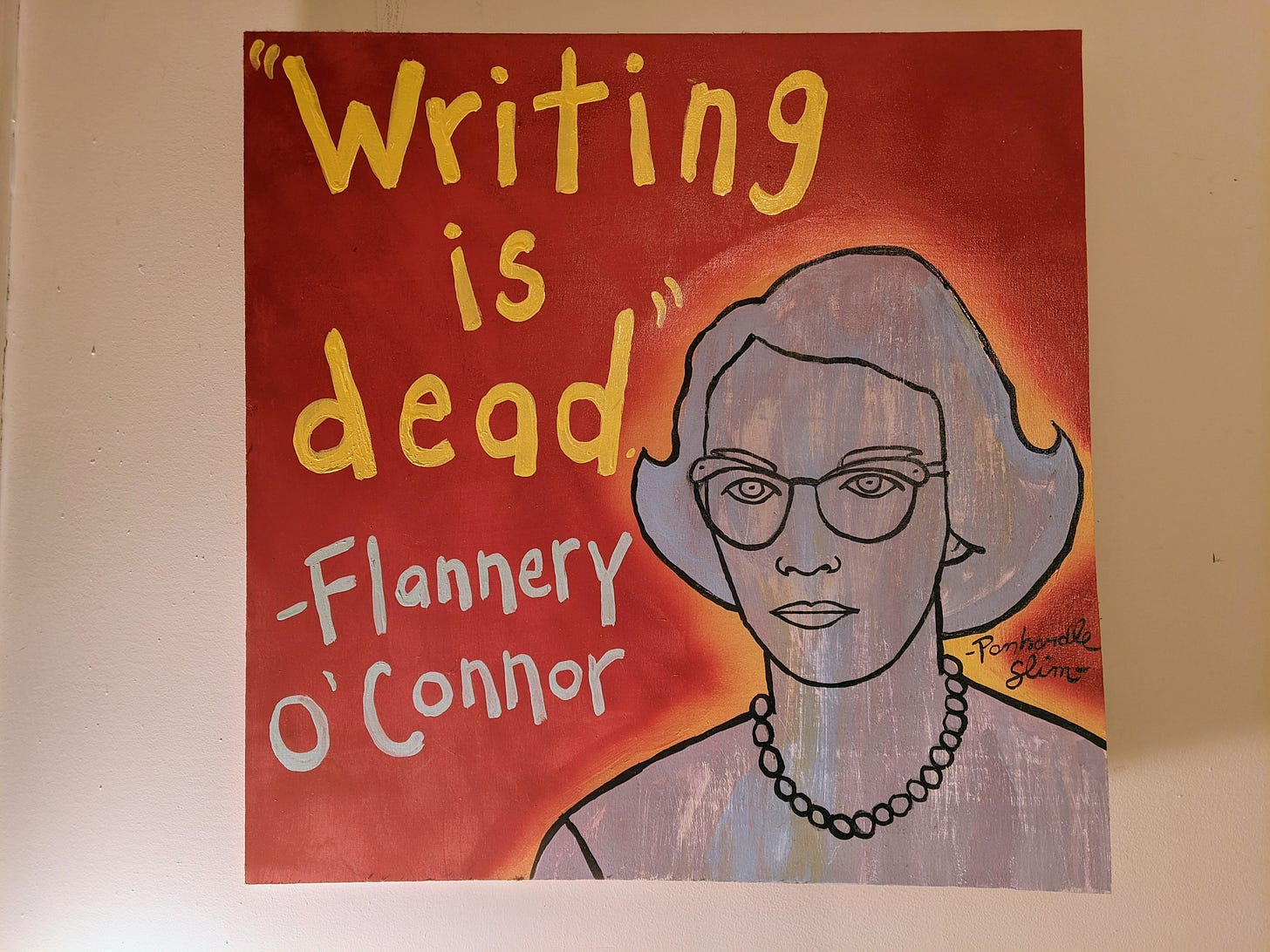

I keep a portrait of Flannery O’Connor above my desk. It has an inspirational quote about writing on it.

“Writing is dead,” the immortal Georgia woman of letters proclaims across the years. I commissioned the painting from Panhandle Slim, a folk artist in Savannah who makes his living doing portraits on plywood boards. He said I could pick any Flannery quote I wanted, and I told him I liked this one best.

Taken out of context, or delivered by someone else, “Writing is dead” might seem like an edgy or defeatist thing to say. It’s neither.

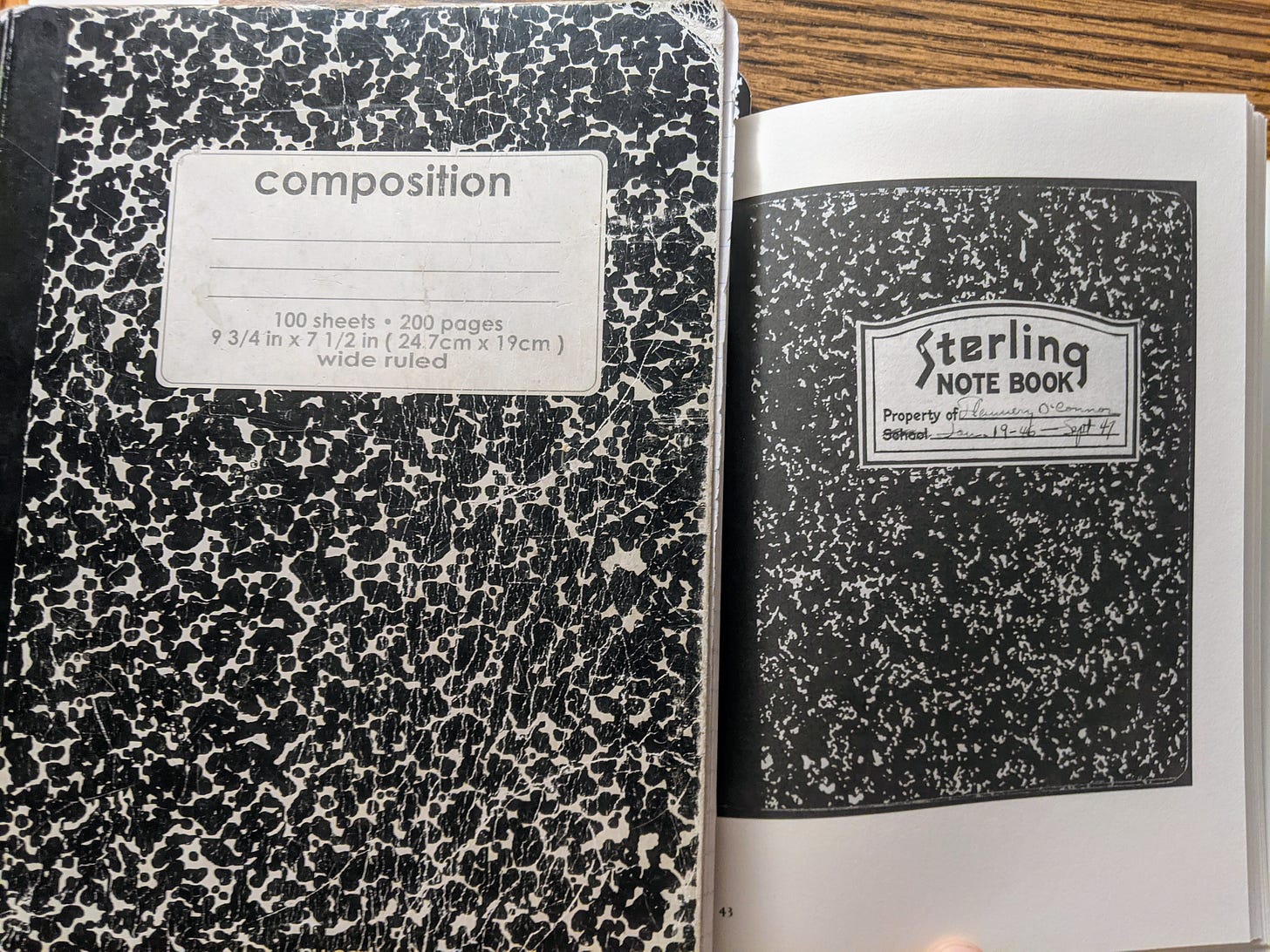

The line comes from O’Connor’s prayer journal that she kept in a marble composition book between January 1946 and September 1947 while attending the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She initially enrolled to study journalism before switching to fiction, and she started writing her first novel, Wise Blood, during the course of the prayer journal.

Far from her family’s peacock farm in Milledgeville and suddenly immersed in the life of the mind, she was struggling to find her footing as a writer and devout Catholic. The culture shock went both ways: Her mentor Paul Engle had such a hard time understanding her syrupy Georgia accent that he asked her to write out their conversations on a notepad.

The inadequacy of language to conjure the fullness of transcendent reality is a recurring theme in the journal. In the final entry, dated Sept. 26, 1947, she wrote, “[T]he feeling I egg up writing here lasts approximately a half hour and seems a sham.” Her written prayers, stories, letters, and essays seem daring and alive when I read them today, but some days they tasted like ash in her mouth.

Here is the full prayer journal entry where I got the quote, dated Sept. 23, 1947:

Dear Lord please make me want You. It would be the greatest bliss. Not just to want You when I think about You but to want You all the time, to think about You all the time, to have the want driving in me, to have it like a cancer in me. It would kill me like a cancer and that would be the Fulfillment. It is easy for this writing to show a want. There is a want but it is abstract and cold, a dead want that goes well into writing because writing is dead. Writing is dead. Art is dead, dead by nature, not killed by unkindness. I bring my dead want into the place[,] the dead place it shows up most easily, into writing. This has its purpose if by God’s grace it will wake another soul; but it does me no good. The “life” it receives in writing is dead to me, the more so in that it looks alive—a horrible deception. But not to me who knows this. Oh Lord please make this dead desire living, living in life, living as it will probably have to live in suffering. I feel too mediocre now to suffer. If suffering came to me I would not even recognize it. Lord keep me. Mother help me.

As a piece of writing, the prayer journal defies genre. The intended audience was God (and occasionally Mary, the mother of Christ). It’s memoiristic at times, although light on personal details. It’s a little bit like confessional poetry. The prayers and pleadings seem raw, but they are not a stream of consciousness. The handwritten journal reveals careful edits: You can see where she scratched out “love” and replaced it with “desire,” and where she replaced “perpetual” with “eternal.”

Christian writers in the American South—particularly the sarcastic ones, the misfits, and those who are disgusted by what Southern Christian churches do in God’s name—have taken up O’Connor as a sort of patron saint. The first time I read her saying that the South is more Christ-haunted than Christ-centered, I knew I had at least found a kindred spirit.

I’ve been reading and re-reading O’Connor’s short stories since college, when my friend the writer Nathan Poole recommended them during a Bible study. I had a full-blown writer crush on her for years; these days I read her with deep love but a little more caution.

I don’t think she would have us read her uncritically, and there are grounds for criticism. At a time when other prominent Catholics were putting their bodies on the line to join the civil rights movement, O’Connor was ambivalent at best about the rights of her Black neighbors. She became close friends with a Black writer at Iowa named Gloria Bremerwell, but as W.A. Sessions noted in the introduction to the 2013 FSG edition of the prayer journal, “O’Connor may not have known that there were no barbershops in Iowa City where black males could get their hair cut at the time.”

She famously turned down an invitation to dinner with James Baldwin. While she sometimes confided in friends that she believed in racial equality (and while her stories themselves sometimes mocked the racial hierarchy of her society), her personal correspondence reveals a pattern of bigoted speech as well as a revulsion at the racial integration of Northern cities. O’Connor fans and scholars engaged in several volleys of argument about all this in 2020 after a New Yorker piece built the case that she was a prejudiced woman.

If she had lived past 39, there is no telling whether she would have repented or turned inward and bitter as the world shifted around her. There is no use speculating about it. Her words are still with us. In one sense they are dead, dead as the day she wrote them. In another sense they live again each time we read them, for better and for worse.

I won’t be as famous as O’Connor, but I do think about the life my words might live when I am gone. Like her, I have sometimes felt that my words signified nothing, or worse than nothing. An essay can be inauthentic just like a prayer or a love letter can be inauthentic. It can be sincere but wholly inadequate.

I was thinking about O’Connor’s prayer journal when my pastor asked me to write a song for our church. The scripture reading this Sunday was Ephesians 2:4-10, in which Paul (or someone writing as Paul) says that we are “created in Christ for good works.” Our pastor was going to preach a sermon on the value of creativity, and she wanted to see if I would write an original song to go along with the service.

I write my songs in a marble composition book that looks a lot like O’Connor’s prayer journal. I write them for selfish reasons, or for my church, or for my family. I have never had ambitions to earn a living with music, but I keep writing songs because they bring me joy.

The passage in Ephesians borrows Jesus’ own metaphor about being “born again” and expands on it a little: “But God, being rich in mercy, because of the great love with which he loved us, even when we were dead in our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ …” The notion of the dead being brought back to life is one of those outrageous religious statements whose force has been blunted by millennia of cliche, but it felt strange and new as I considered it in the context of creative work.

Following the pattern of a lot of church music and liturgy, I wanted to start my song with lamentation. I cribbed most of the first verse from O’Connor’s prayer journal.:

“Abstract and cold,

A dead want that goes well in writing

‘Cause writing is dead.

Writing is dead.

Art is dead”—

Sometimes I don’t feel so hot myself.

I read the lines out loud to get a vague sense of meter (loose, like a chant), then I picked up my guitar and tried a few chords.

There are only so many chord progressions out there, so I started with the chords from a song I’d been enjoying, The Mountain Goats’ “Parisian Enclave,” and tooled around with them a little bit. Eventually all I kept was a transition from A minor to G, with some walking bass thrown in for flavor.

I wanted the next verse to be about the promise of grace. I started with antonyms to O’Connor’s “abstract and cold” to set the verses apart:

Solid and warm,

New life you have promised,

I’d take it if I never spoke again.

Old but reborn,

Emptied to fill,

Hollowed out to be colored back in.

Hey, I even made that verse rhyme! Now I was getting somewhere.

I wanted the chorus to convey the same message as Derek Webb’s “Mockingbird” (the title track from a perfect Christian rock album, if you’re asking me): that nothing I can sing is new, that I only sing back an echo of the divine. I came up with this:

I can’t boast

I can’t sing the truth out loud

‘Cause at most

I am singing back the

Songs you sang

To me when I was

Six feet underground

By now I was maybe letting my Southern Baptist roots show. My current enclave of Methodist friends doesn’t much sing about death and blood, for what I now recognize as sound theological reasons. Their conception of salvation (and mine, these days) is not so much about granting believers a Get Out of Hell Free card as it is about becoming spiritually whole and spiritually alive, and participating in the renewal of the world.

So I went for some nature metaphors in the next verse:

Raised with the rain

Like ferns on the limb

Of a live oak that held on til spring

Words can’t explain

Nor art ever limn

The new life that new creation sings

I know I rhymed “limb” with “limn,” and that’s more than a little confusing when you say it out loud. But I meant those words precisely, and anyway I was on a deadline.

I finished the song Saturday night and sang it in church Sunday morning. It went OK, I think! A few friends told me they enjoyed hearing me sing, and no one accused me of blasphemy to my face. With a few days’ distance, I still like how it turned out.

I am in a season of life when my words feel more alive than dead, mercifully. It wasn’t always this way, and it won’t be this way forever. I’ll bring my dead desires to a dead place again. Up above my desk, I’ll see Flannery smirking and know that I’m not alone.

***

If you’re interested in a lyric and chord sheet for the song, just reply to this email and I’ll send it to you.

Flannery O’Connor’s A Prayer Journal is a strange and bracing read. You can order it via the Brutal South Bookshop page, where a portion of each sale goes to me and another portion goes toward a general fund distributed to independent bookstores.

If you liked today’s newsletter, you might appreciate these issues from the archive:

All hail the mysterious gap (about the Mountain Goats, Rich Mullins, and sincerity in lo-fi music)

Everyone loves a good train wreck (about the train crash at Crush, Texas, and why I decided to write a song about it)

Two new Christmas songs (with chord sheets!) (a subscriber-only issue featuring two Christmas songs I wrote for my church)

Brutal South is free every Wednesday. Please consider supporting my work with a $5-a-month subscription that gets you access to ~ subscriber-only exclusives ~

Bookshop // Twitter // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts