I was climbing into bed the other night when I heard a crack and a thud. The sound seemed to come from everywhere at once; I felt it as much as I heard it.

It was after midnight and the sky had been dumping rain for two straight days. I rushed to the front of the house and checked the kids’ bedrooms. All safe. I grabbed a flashlight and stumbled out into rainfall that had slowed to a misty spit. Slogging through ankle-high water, I swept my beam along every edge of the house. Found nothing. Went back inside and sat bolt upright for an hour before falling asleep.

The next morning I stepped out on the porch and saw what I had missed: A massive oak had split along its trunk in my neighbor’s backyard. Half was still standing; the other half was covering his entire backyard, part of our fence, and a tool shed that it had flattened. The exposed interior of the trunk didn’t look rotten or lightning-scorched; it had simply given way. We were all lucky it fell where it did.

I broke the news to my neighbor, who had somehow slept through the night, and he took it in good humor. He had just cut some dying trees down earlier this year, but he’d saved this one because it looked beautiful and healthy and strong enough to weather a few more hurricane seasons.

People on my block watch out for each other. The same neighbor who lost the oak helped me chop up a gum tree limb that fell into the street several years ago, and I offered to get a chainsaw and do the same for him. Over the years our block has had stray cats, spazzy dogs, livestock, loud kids (ours), backyard beekeeping operations, shitkicker house parties, fireworks at odd times of year, and the occasional bizarro yard art installation. The ethos is live-and-let-live, but we will also help you live.

The people here are, in a word, neighborly. I want to be precise about that term. A neighbor is a less intimate acquaintance than a family member or a friend. You might see a neighbor walking their dog a hundred times before working up the nerve to start a conversation. But when a neighbor asks for help, you feel a sense of duty even if you’ve never learned their name.

Who is my neighbor, and what do we owe each other? Those are old questions. One of the most important commandments in my faith tradition is “Love your neighbor as yourself.” (Another, less popular one is “Love your enemies,” which I’ll get to in a little bit.)

The French existentialist Simone de Beauvoir wrote in Pyrrhus and Cineas in 1944:

When the disciples asked Christ: who is my neighbor? Christ didn’t respond by an enumeration. He told the parable of the good Samaritan. The latter was the neighbor of the man abandoned in the road; he covered him with his cloak and came to his aid. One is not the neighbor of anyone; one makes the other a neighbor by making oneself his neighbor through an act.

I’ve heard a lot of sermons attempting to explain the parable of the Good Samaritan. In conservative churches it’s a story about helping strangers through personal charity. In more progressive churches you might hear a pastor explain how Samaritans were treated as second-class citizens by the dominant culture, and how the Samaritan’s gift was all the more remarkable for his low stature in the community.

But I appreciate Beauvoir’s explanation for its simplicity. Nobody in the parable is anybody’s neighbor, until the Samaritan makes himself a neighbor to the man stranded in the road. He distinguishes himself through action.

***

I have been thinking about the scope of neighborly action beyond my own block. Right now we’re all facing at least two crises that test the limits of neighborly obligation at a global scale: The COVID-19 pandemic and climate change, which will topple a few more sturdy oaks before we’re gone. In both cases, looking out for the neighbors in our immediate geographic area won’t suffice. Our fates are intertwined now.

The concept of mutual aid is useful here, especially in contrast to the one-sided nature of charity. When my Democratic Socialists of America chapter got involved with mutual aid efforts for Louisiana residents after Hurricane Ida last month, an unspoken assumption was that we would one day find ourselves in need of the same care. With tropical storms increasing in frequency and intensity within our lifetimes, it’s not a question of whether but when.

I was working as a newspaper reporter in October 2015 when a massive storm hovered over South Carolina and dropped as much as 25 inches of rain on the Lowcountry. The Ashley and Edisto rivers crested their banks, people’s homes were destroyed, and I went out in a kayak to interview people and photograph the worst day of their lives.

In the middle of all that, I got a text from an old work acquaintance who was guiding a foreign photographer around the state documenting the damage. He wanted tips for location scouting.

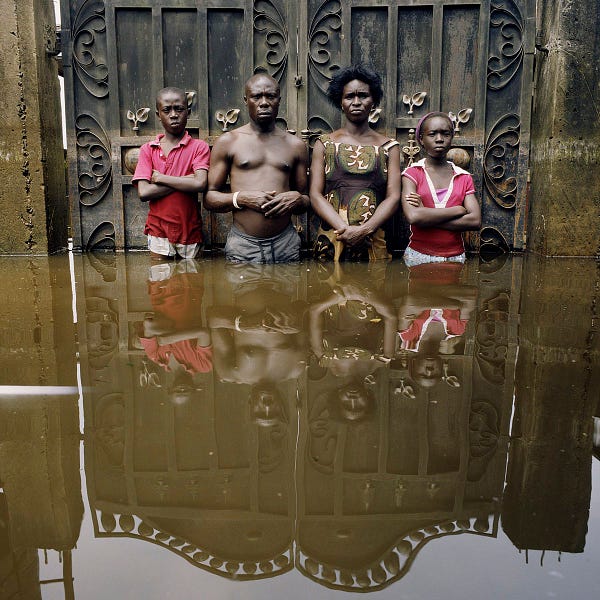

The photographer was Gideon Mendel, and he was working on an ongoing photo essay called Drowning World. All over the world, he photographs people standing waist-deep, chest-deep, even neck-deep in water near their homes.

This is probably a symptom of my own provincialism, but when I looked up Mendel’s work, I felt dizzy seeing South Carolinians striking the same eerie pose as their counterparts in Nigeria, Brazil, and Pakistan. Intellectually I knew the water was rising everywhere, but I felt it in my gut when I saw the depth measured on human yardsticks.

When the next big storm comes, we will muck out our houses and rebuild. Before long, and with increasing regularity, communities elsewhere in the world will be doing the same thing. So, who are my chosen neighbors? Where to begin the work, and how to define its scope?

One insight from the existentialists is that we are all free — terrifyingly, at times nauseatingly so. None of our lives have meaning, and none of our social ties are real, unless and until we make them meaningful and real.

Here’s Beauvoir again, from her essay What is Existentialism?:

[T]he task of man is one: to fashion the world by giving it a meaning. The meaning is not given ahead of time, just as the existence of each man is not justified ahead of time either …

Cut off from human will, the reality of the world is but an ‘absurd given’. This is a conception that appears to many people as hopeless and makes them accuse existentialism of being pessimistic. But actually there is no hopelessness, since we think that it is possible for man to snatch the world from the darkness of absurdity, clothe it in significations, and project valid goals into it.

In the face of near-certain catastrophe, there’s a temptation to nihilism: The world is ending; why should I bother? But in another way our actions in the next 20 years will be among the most meaningful actions (or inactions) in human history. The latest IPCC report predicts that by limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, as opposed to 2 degrees Celsius, we could reduce the number of people exposed to climate risks and poverty by 457 million. Ought we not fight like hell for that half-degree?

***

Saying “everyone is my neighbor” is effectively the same as saying “no one is my neighbor.” Human attention and care can’t spread that thin, and for that reason it’s a useful exercise to consider who, exactly, I want to treat as my neighbors.

There is another important category in my faith tradition, and that’s the category of the enemy. King David wrote whole psalms begging God to snuff out his enemies, and Jesus taught us — bafflingly — to love our enemies.

But it is not popular in a neoliberal democracy to have enemies per se, at least not domestically. “To make progress, we have to stop treating our opponents as enemies,” the president of the most powerful empire on earth said recently. This is wishful thinking at best.

Who are my enemies? I know my enemies when I see them oppress the neighbors I choose. When a person harms someone I love through policy or violence or cruelty, that person becomes my enemy.

What am I supposed to do about my enemies? If I wish for their suffering, it’s not without precedent (“May his children be fatherless and his wife a widow,” David ranted in Psalm 109).

I am thinking of the particular flavor of schadenfreude that comes from reading about yet another right-wing talk show bigot or anti-vaccine crusader dying of complications from COVID-19. The humor of the Herman Cain Awards is lost on me, but sometimes a death can feel like cosmic justice, even when it isn’t.

Is it wrong to savor another person’s comeuppance, particularly when that person has actively made the world more dangerous for my neighbors and me? I don’t know, actually. It’s probably not good for the soul, but one person’s feelings of vindication or mockery won’t affect the world at large.

Jesus said to love our enemies, but I think we fall short of that commandment by acting as if we have no enemies. Caesar was an enemy of the early Christians, and the people caging our Black neighbors and rigging up modern crucifixes and turning away desperate Haitian asylum seekers at the border are surely our enemies today.

Enemy-love is confounding and countercultural. Martin Luther King Jr. preached love for enemies as he joined and led a movement of mass nonviolent resistance. The Rev. Sharon Risher does it when she fights against the death penalty for Dylann Roof, the white supremacist who killed her mother and family members at Emanuel AME Church. Loving your enemy can earn you more enemies than friends.

I don’t know what loving my enemies in the fossil fuel lobby and the Christian anti-mask crusade will look like. Whatever it means to love our enemies, the commandment begins with an acknowledgement that we might have real enemies.

I’ll leave you with this line from Gustavo Gutiérrez, in A Theology of Liberation:

‘Love of enemies’ does not ease tensions; rather it challenges the whole system and becomes a subversive formula. Universal love comes down from the level of abstractions and becomes concrete and effective by becoming incarnate in the struggle for the liberation of the oppressed.

We will have to struggle, in the near future against the pandemic and in the long term against climate change. Along the way, it will be important to know whom we are struggling for and whom we are struggling against.

***

Brutal South is a free weekly newsletter and occasional podcast. Paid subscribers ($5/month) get cool logo stickers and a whole bunch of exclusive content.

One organization laboring for environmental justice in my part of the world is Friends of Gadsden Creek. They have some calls to action at friendsofgadsdencreek.com if you would like to join their work.

One fight that my DSA chapter has joined is the Green New Deal for Public Schools campaign, which seeks to invest $1.4 trillion in public schools to fight climate change and climate racism. Learn more at greennewschools.com.

In addition to the thin Penguin edition of Beauvoir’s What Is Existentialism? that I quoted in the newsletter, I found two pieces of media especially edifying this week. One was Episode 39 of the Know Your Enemy podcast, featuring Daniel Sherrell and Dorothy Fortenberry talking about how to live and parent and build an effective political resistance to the fossil fuel death cult during the Anthropocene era. The other was this Ben Wildflower interview on Christian anarchism in Killing the Buddha.

In other news, my band The Camellias will release a 25-track album of home recordings called Words Are Fragile Vessels on Oct. 5 at camellias.bandcamp.com. Holy City Sinner was kind enough to run a short preview here.

Twitter // Bookshop // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts