Two decades of imperial dramaturgy

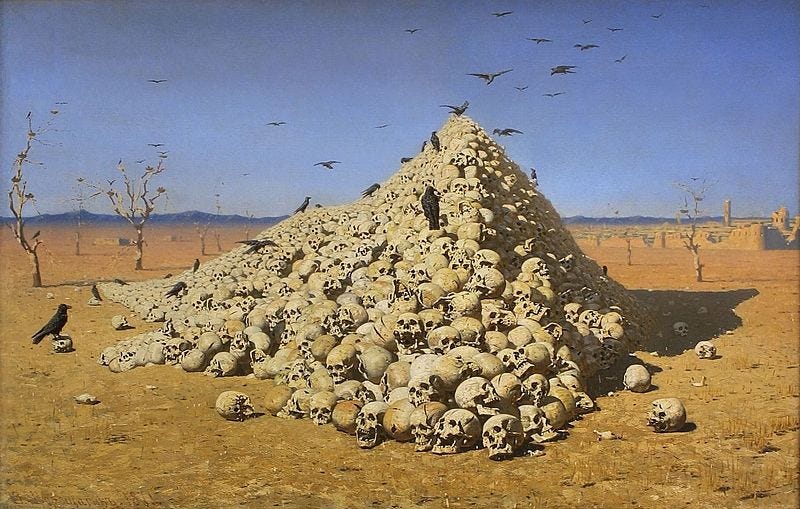

After 9/11, we brought the sins of a global empire home to south Georgia

Right around September 11, 2019, some journalists dug up an ominous government contract. For about $1 million, a training company called Strategic Operations Inc. was going to build simulations of American cities at Fort Benning, Georgia, for agents of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to train for raids on migrants.

The purpose of the project was to recreate “combat conditions” using the company’s patented “HYPER REALISTIC” technology, which included “urban warfare training services,” replicas of urban and suburban homes, simulated rocket-propelled grenades, simulated improvised explosive devices, and simulated combat wounds. By recreating a warzone in a familiar domestic context, the company claimed it could inoculate ICE agents against stress and the “fog of war.”

The purchase documents called for an “‘Arizona’ style replica” and a “‘Chicago’ style replica,” with the option of “additional U.S. city layouts and designs” in later expansions. The San Diego-based company promised Hollywood-quality special effects; role-playing actors fluent in foreign languages; and painstaking realism in its set dressing, right down to the kitchen appliances and children’s toys.

The timing of the news item, near the anniversary of the 2001 terrorist attacks, was an uncanny coincidence. The Department of Homeland Security (created in 2002) and its child agency ICE (created in 2003) are distinctly post-9/11 outgrowths of the U.S. military and police regime. Hastily created in a crucible of nationalism and paranoia, they grew to command budgets in the tens of billions of dollars while opening up new domestic fronts for surveillance, bondage, and torture.

As we approach the 20-year anniversary of the September 11, 2001, terror attacks, I’ve been thinking about a phenomenon that the writer Geoff Manaugh called “imperial dramaturgy.” I don’t know if he coined the term, but the first place I saw it was in his description of the Fort Benning ICE facility:

Law-enforcement training facilities have always fascinated me, insofar as they rely upon a kind of theatrical duplicate of the world, a ritualistic microcosm in which new techniques of control can be run, again and again, to perfection. Architecture is used to frame a future hypothetical event, but with just enough environmental abstraction that the specific crisis or emergency unfolding there can be re-scripted, often dramatically, without betraying the basic space in which it occurs. It is imperial dramaturgy.

However, simulated training environments are also interesting to the extent that they reveal what, precisely, is now considered a threat. In other words, we train for scenarios precisely when we fear those scenarios might exceed our current preparation; training, we could say, is a sign of worry. The fact that ICE is apparently—based on this document—prepping for “combat conditions” in “‘Chicago’ style” structures, complete with dishes left on the table and toys left sitting outside in the yard sounds almost absurdly ominous.

“Imperial dramaturgy” is also a useful term for more recent developments, including the proposed “Cop City” police training center in DeKalb County, Georgia, which could soon be built on the site of a former prison farm despite widespread protests in Atlanta.

Manaugh used the term “imperial dramaturgy” to describe the theatrical training regimen of imperial forces. But in the two decades since 9/11, the general public has received some training as well.

Rapidly at first, and then at a slower ratchet, we have come to accept as normal a whole array of disciplinary and punitive acts: strip searches at the airports, surveillance of mosques, widespread warrantless wiretapping and metadata collection, and facial recognition databases generated by doorbell cameras and maintained by an unaccountable police and carceral state.

A sizeable portion of the military equipment that we didn’t just donate to the Taliban has ended up in the hands of U.S. police departments and sheriff’s offices via the Department of Defense 1033 Program, a Clinton-era creation that mushroomed as U.S. weapons flooded the global market post-9/11.

As a result of this backflow of military gear, my mid-sized Southern city now owns two MRAP (Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected) vehicles and enough assault rifles to arm a junta. We’re no longer shocked when the cops drive an armored car into a crowd of peaceful protesters or shoot them with abortifacient chemical weapons. A neighboring city’s police department even pulled up to a “trunk or treat” Halloween festival in a hulking MRAP a few years ago for a tactical candy distribution mission.

Based on local reports from the Columbus, Ga., Ledger-Enquirer, it looks like the ICE facility at Fort Benning was completed despite the public blowback when the news broke in 2019, and ICE remains a major presence on and around the base in southwest Georgia. At least four ICE detainees have died of COVID-19 complications while in custody at the nearby Stewart Detention Center — a larger number than at any other ICE detention center as of June, according to Georgia Health News.

***

The location of the ICE training facility near the Georgia-Alabama border is notable. Fort Benning is also the home of the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC), better known by its former name: The School of the Americas.

The first predecessor to the School of the Americas was founded in what is now Panama in 1946. Throughout the Cold War and beyond, the facility trained U.S.-friendly dictators, military brass, and death squad leaders. As the School of the Americas grew, moved to Georgia, and rebranded, it enabled the U.S. to establish and maintain hegemony while arranging for the assassination of progressive leaders and the massacre of indigenous communities throughout the western hemisphere. Notable alumni include Panamanian military dictator Manuel Noriega; Bolivian dictator Hugo Banzer Suárez; Chilean secret police chief Manuel Contreras; and Salvadoran death squad leader Roberto D'Aubuisson, who ordered the assassination of Saint Óscar Romero.

The School of the Americas rebranded as WHINSEC in 2001. By some accounts, its tactics remain fundamentally the same.

The school at Fort Benning was a quintessential product of the Cold War, when a major objective was killing and defeating “communists,” as identified by the U.S. intelligence community. With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the school entered the War on Drugs with a focus on killing and detaining “narcoguerrillas,” according to anthropologist Lesley Gill. By 2001, its purpose had crystallized along with the rest of the U.S. military and intelligence community: It was now training a new generation to hunt “terrorists” and eradicate “terror.”

Whereas the School of the Americas traditionally aimed its gaze outward, ICE arrived at Fort Benning with a focus on raiding communities within U.S. borders. With the creation of an urban warfare training facility, the agency trained the weapons of war on the American interior.

***

Watching the escalation of police violence against civilian protesters in Portland, Oregon, last year, the historian Patrick Wyman made the observation that U.S. forces’ impunity abroad certainly seemed to be coming back home:

At times like this, when the empire abroad starts to come apart, domestic blowback is a common consequence. Empires, and imperial failures, rarely stay out of sight and out of mind if they become an ongoing pattern. The tools of empire don’t stay overseas, trained solely on those designated as the empire’s enemies; they find new targets, new uses, in the hands of people looking to grab the shreds of power left behind as the empire collapses in on itself.

It’s hardly a novel observation by now, but U.S. law enforcement agencies are thoroughly militarized. They are trained by military consultants, armed with military equipment, and sent into communities with the logic of counterinsurgency to arrest civilians at a rate higher than any country on earth.

I haven’t visited the ICE training grounds at Fort Benning, but I have visited a similar facility just over the border from Georgia in South Carolina. In April 2018, while working as a reporter for the Charleston Post and Courier, I visited the Government Training Institute, a privately owned law enforcement training compound in Barnwell, S.C.

I was there to solve a mystery. On the night of March 28, a series of explosions at the Savannah River Site rattled people’s china cabinets as far away as the next county. GTI, which inhabits a towering concrete block within the government-operated nuclear technology compound, claimed responsibility in a vague statement to the People-Sentinel the next day:

“Regarding the events that transpired on the evening of March 28, a classified training operation was conducted at The Government Training Institute (GTI) where several moderate explosions were heard in the surrounding communities.” (The full statement and ensuing Facebook comments are an interesting read.)

I never got a clearer answer about what caused the mysterious explosions (“Classified,” CEO Von Bohlin insisted). But I did get a good picture of what happens routinely at the Institute.

GTI operates out of a decommissioned nuclear fuel processing facility. While it doesn’t bear much resemblance to a modern U.S. city, its maze of catwalks and corridors can be set up to simulate all kinds of firefights, explosive door breaches, and IED detonations as required.

GTI was founded in 2003, the same year as the Department of Homeland Security, by military veterans in Boise, Idaho. The company worked with DHS to create classes like “Advanced SWAT Operations for Terrorist Environments,” “Improvised Explosive Devices” and “Rapid Law Enforcement Tactical Response to Violence and Terrorism in the School Setting.” Law enforcement agencies across the country started sending officers to train at GTI.

In 2008, GTI moved into the decommissioned nuclear facility in Barnwell, S.C. The imposing concrete building was very much a beast of the Cold War, but now it serves the purposes of the Global War on Terror.

“There was a big wall between law enforcement and the military,” said GTI Vice President Brian Naillon. “We helped crumble that wall.”

They crumbled the wall, and so did Dave Grossman, creator of the wildly popular “Killology” seminars for cops and church leaders. So did ICE and all the politicians who created and enabled it. So did every small-town police chief who strapped his officers with dirt-cheap military surplus rifles. And the wall isn’t going back up.

***

Brutal South is a free weekly newsletter and podcast. Paid subscribers ($5/month) get access to exclusive stuff, like Brutal South vinyl stickers, an original audio novella, and this piece I wrote last week about Satan and kitsch.

A little housekeeping: If you ordered a Brutal South T-shirt, Turning Leaf tells me they’re scheduled to start shipping out on Friday! I’m excited to see them out in the world. By my last count I sold at least 70, which is way more than I thought I would. Please send pics of yourselves looking metal as h*ck in those shirts.

In other news, I stayed up the other night in a Sudafed-induced haze and did some arts and crafts. I now have a cover for the upcoming album by my little folk music project The Camellias. It’ll be available soon at camellias.bandcamp.com.

Twitter // Bookshop // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts