Twang against the machine

The Dixie Chicks saga in South Carolina didn’t happen quite like I remembered it

Backstage at the Bi-Lo Center on May 1, 2003, someone told the Dixie Chicks the good news: President Bush had declared an end to major combat operations in Iraq.

“The president just announced the war is over,” lead singer Natalie Maines told the arena crowd in Greenville, S.C., as the band launched into an encore. The audience went wild.

It was a fateful crossroads for the world’s most famous Texans. The Chicks had ignited the hottest country radio drama of the year shortly after the U.S. invasion of Iraq in March 2003 when Maines finished singing the song “Travelin’ Soldier” and told a London concert crowd, “Just so you know, we’re ashamed the president of the United States is from Texas.” With pro-war jingoism running high in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, the chart-topping band found itself pulled from the air on radio stations across the U.S.

I was thinking about the Dixie Chicks brouhaha this week after listening to the latest episode of the podcast You’re Wrong About, which compared the band’s public shunning to the present conservative panic over “cancel culture run amok.”

The episode was a window into the deranged war frenzy of the early 2000s, which is easy to forget if you weren’t deployed or being actively invaded at the time. Co-hosts Michael Hobbes and Sarah Marshall dug up contemporary news coverage that showed how mainstream political and cultural figures deployed misogyny, racism, and even fatphobia to put modestly outspoken women in their place.

With nearly two decades’ hindsight, the Chicks were obviously right and the “Mission Accomplished” speech was a bit of world-historical hubris. The U.S. occupation of Iraq dragged on until 2011, and the majority of the bloodshed took place after Bush’s speech.

I’d encourage you to check out the whole episode, which was illuminating as usual. Today I thought I’d spend some time digging into the role my home state of South Carolina played in the story.

***

South Carolina wasn’t unique for heaping scorn on the Chicks. As Hobbes and Marshall explained on the podcast, internet message boards quickly organized to bombard local radio stations across the country with angry calls about the band. A few hundred calls from a dedicated legion of cranks was often enough to overwhelm a small-town broadcaster, and many stations including South Carolina’s own WEZL (“The Weasel”) pulled the Chicks from the airwaves within days.

What set South Carolina apart was its role as home to the Chicks’ first U.S. concert after the London scandal. As luck would have it, that concert was scheduled for an arena in the deep-red conservative city of Greenville on May 1, 2003. Amid death threats, CD-smashing rituals, and frothing rage from the pundit class, the Chicks hired bodyguards and geared up to play their first show back in their home country.

Conservative politicians in South Carolina took their bit of leverage and ran with it. Nine days after the London concert, the South Carolina House of Representatives passed a resolution by a 50-37 vote demanding that Maines issue an apology for her “unpatriotic and unnecessary comments” before the Greenville show and that the band play a free concert for South Carolina military members.

The Charleston Post and Courier quoted the bill’s author, Rep. Catherine Ceips (R-Beaufort), on March 19, 2003:

“Only in America would a group of women like them be able to follow their dreams. They could not do that if they lived in Iraq,” Ceips said.

“They need to know the seriousness of our nation and what our men and women in our military do. We have a rich military history here in South Carolina. It hurt my feelings and I know it hurt the military families that I support in my town and across the state,” she said.

Meanwhile, talk radio host Mike Gallagher juiced the controversy by organizing an anti-Chicks concert in nearby Spartanburg, S.C., featuring the Marshall Tucker Band. He offered VIP passes to anyone who traded in their Dixie Chicks tickets, hung an enormous U.S. flag onstage, and rounded out the concert with a tribute to a Marine from the South Carolina Upstate who had died in Iraq.

Across the state, newspaper editorial boards continued their proud tradition of being wrong about everything. The Greenwood Index-Journal opined on April 25, 2003, that the band should stop “whining” about death threats:

Remember, it was lead singer Natalie Maines who had something nasty to say about our president while performing in London. Now they are whining because they believe the response to their comments has been unreasonable. They say they have been the target of threats, boycotts and property damage.

Threats and property damage are indeed out of place. They should know, though, that it’s a fact of life that you sleep in the bed you make. (emphasis mine)

Maines, for her part, never really apologized for the offhand remark about being embarrassed of Bush, except to tell Diane Sawyer that she had used the “wrong wording.” The band never played the free military concert that the South Carolina legislature had demanded.

***

South Carolina lawmakers have a long track record of ineffectual flailing, and 2003 was a banner year. The same year, the state House voted 90-9 for a concurrent resolution against purchasing French goods and services due to “French opposition to the plans of the United States to use military force if necessary to disarm Iraq of weapons of mass destruction.” (Denny’s, which has its global headquarters in Spartanburg, also considered rebranding its Fabulous French Toast as Fabulous Freedom Toast, but ultimately took no action.)

As Hobbes and Marshall discussed on their podcast, the Chicks firestorm was a template for 21st-century conservative culture wars. Thanks to quick responses from conservative online communities, it is no longer necessary to drum up grassroots local support for a quick-hit smear campaign. By “working the refs” and whining constantly about anti-conservative media bias, cultural conservatives get to wield hegemonic power while simultaneously playing the aggrieved underdog at all times.

In the end, there was little evidence that the campaign to “cancel” the Chicks had a strong base in South Carolina. Metal detectors were installed at the Bi-Lo Center, and local police set up a designated “free speech zone” outside the venue, but the much-hyped culture clash never gained traction.

Post and Courier columnist Brian Hicks attended the Chicks concert in Greenville and reported that the scene “was a little light on protesters, defying the best media predictions.” Describing the scene a few hours before the concert, he wrote:

There were exactly two guys — one anti-Chicks, the other anti-Bush — milling about Thursday and, having little else to do, they chatted amiably while the 100 or so reporters on hand stood in line to interview them.

Charles Crowe of Anderson, who wore a George W. Bush hat and held up a sign that had “Dixie Chicks” marked out, replaced with “French Hens,” pointed to his competing protester, who held up a “Bush Sucks” sign, and said, “We’re being friends even though he’s got that sign.”

A few more protesters showed up closer to the time of the concert, but the clash was much tamer than the national media blitz would seem to indicate. Inside the arena, Maines addressed the controversy head-on.

“If you’re here to boo, we welcome that because we believe in free speech,” Maines said. “So if you want to boo, we’ll be quiet and let you, on three … One, two, three.”

The crowd went wild.

An enduring irony of the Chicks v. Bush saga is that the song that started it all, “Travelin’ Soldier,” is an empathetic war ballad that captured the feeling of the Iraq War for a lot of military families. It was more doleful than angry, a far cry from the bomb-dropping bravado of a song like “Courtesy of the Red White and Blue.”

Written by Texas songwriter Bruce Robison, “Travelin’ Soldier” tells the story of a heartbroken teenage girl waiting for a soldier to come home from war. (The narrative is set during the Vietnam War, which, in retrospect, is a fitting stand-in for the Global War on Terror.)

One Friday night at a football game

The Lord's Prayer said and the anthem sang

A man said folks would you bow your head

For the list of local Vietnam dead

Crying all alone under the stands

Was the piccolo player in the marching band

And one name read and nobody really cared

But a pretty little girl with a bow in her hair

The bombastic boot-in-your-ass anthems of early-2000s country radio helped sell a doomed war to a desperate public. Looking back, we could have used more songs about the heavy cost of war.

***

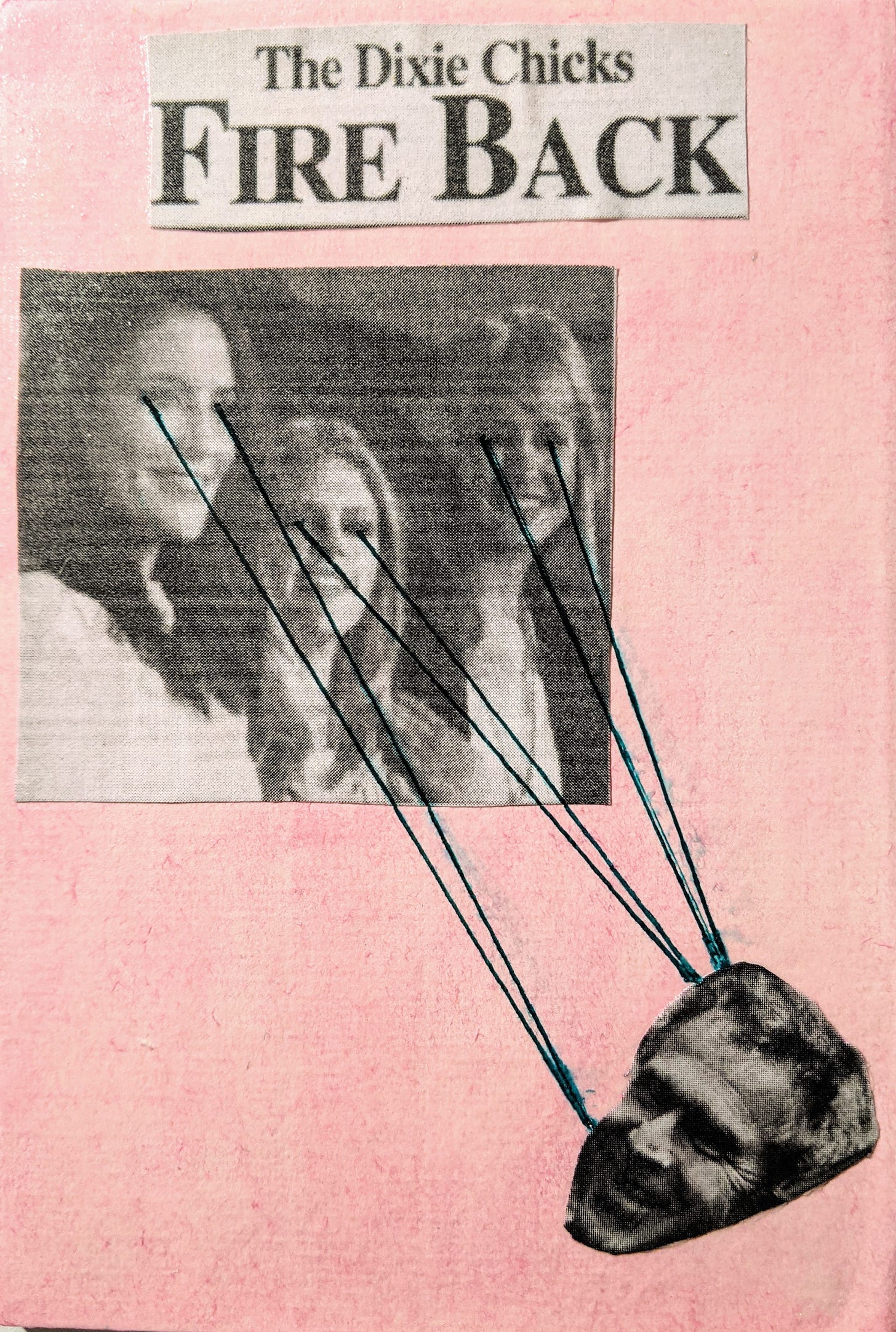

I made the collages in this issue with newspaper clippings and Mod Podge.

Brutal South is a free weekly newsletter and podcast. To support my work and get access to subscriber-only issues and episodes, plus some stylish vinyl stickers with the Brutal South logo, please consider becoming a paying subscriber for $5 a month. See more details here, or click the Subscribe Now button to get signed up.

Twitter // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts // Bookshop // Bandcamp

I love the statement "South Carolina lawmakers have a long track record of ineffectual flailing"...nothing truer has ever been said. :-)