I don’t know about you, but I am so far behind on personal and professional correspondence, I feel like I’ll never catch up. It’s been a long week, a long year, and a long decade.

I know I’m toeing the line between self-forgiveness and self-indulgence here, but this week I am republishing a piece I originally wrote for paid subscribers on June 7, 2021. The original title was “The weight of correspondence.” I changed it to something a little less pretentious this time.

Before we get going, I have one timely announcement and call to action. The South Carolina Senate Subcommittee on Education is holding a hearing today about H. 3728, a teacher censorship bill that has already passed in the House. It’s the same hot garbage conservative lawmakers have been slinging around in every state legislature this year. It would threaten teachers’ careers for straying from the hard-right party line on matters of race, history, sexuality, and gender.

The ACLU of South Carolina and ProTruth SC have more information and links to contact state senators about the bill. I also wrote 2-ish pages of notes on the havoc this bill would cause in schools, and you can read those notes here. Please join us in speaking up now. In the event that the Senate doesn’t listen, we’ll need to break this law forcefully, creatively, and often.

I am never going to read the 10,506 unopened emails in my inbox. Most of them are spam or automated emails or, recently, newsletters that I signed up for and never had the time to read (I know, I know).

Buried in there are a few personal emails from friends, loose threads that I left dangling as we drifted apart. I tell myself I might pick them up again one day, but then I consider the guilt I would feel about a years-long gap in correspondence.

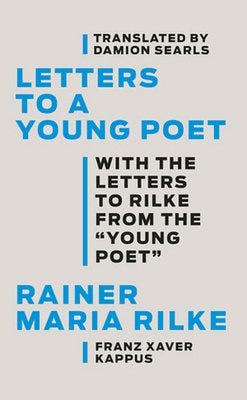

I recently read a 2021 translation of Letters to a Young Poet, a collection of letters from the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke to a younger protégé between 1903 and 1909.

The new translation by Damion Searls is the first to include the other side of the conversation: the letters written by the protégé, a lesser known poet named Franz Xaver Kappus. I was struck by the long gaps between some of the letters.

The Letters have been a sort of scripture to several generations of artists. Lady Gaga has a passage tattooed on her left arm. They contain a lot of tenderness and wisdom, and creative people have sometimes felt as if the letters were addressed to them during hard times.

Kappus’ letters are a nice addition to a classic piece of literature. He confesses insecurity and lavishes praise on his long-distance mentor, who had no obligation to answer out-of-the-blue fan mail but did anyway.

Reading the letters, I recognized a custom that has survived in the digital age: the brief opening apology for not replying sooner. My favorite might be Rilke’s from the start of Letter Four, dated July 16, 1903, after a 10-week pause:

My dear Mr. Kappus: I have left a letter from you unanswered for a long time—not because I’d forgotten it; on the contrary: it was the kind of letter one reads again and again when it turns up among one’s other correspondence, and I could see you and feel you in it as though you were very close.

I have never written such an elegant apology, but I have felt the same way: Someone wrote me a kind or profound or interesting note, and I started and stopped responding several times before hitting Send, wanting to make sure my response was at least half as kind or profound or interesting. There is a weight to correspondence like that, and I can’t bear to dash off a curt acknowledgement on my phone. I need to respond in kind.

Rilke’s early letters were the sort of generous responses anyone would dream of receiving from their hero. There is a reason the letters have endured as a sort of devotional that people re-read and savor over the course of a career.

The tone of the letters shifted later on, though. On Aug. 27, 1904, Kappus wrote a long confessional letter to Rilke in which he mentioned, at age 13, having thrown his male friend on the ground and “loved him and kissed him as I’ve barely done with a girl since.”

This was followed by a gap of 69 days — one of the longest yet — before Rilke responded with a short letter, reassuring Kappus that “everything you can remember about your childhood is good,” and offering an apology for the long wait (“I’ve had to write so many letters that my hand is tired”).

Rilke’s letter was dated Nov. 4, 1904. It was followed by nearly four years of silence.

It was Rilke himself who broke the silence with a now-lost letter on Aug. 30, 1908.

Why the long pause? We don’t know. At first I imagined Kappus might have felt a little miffed about the curt response to one of his most openhearted letters.

An editor’s note on the lost letter of 1908 offers another hint: Kappus had sent some of his own poems to Rilke’s publisher in Berlin in late 1907 and received a form-letter rejection. “Rilke had felt he couldn’t recommend Kappus’s poems for publication and had had the poems returned to Kappus via a Vienna book dealer [in 1907], without the accompanying letter he had planned to write.”

These two men had a tenderhearted friendship, but they also had a sort of business relationship: Rilke was an up-and-coming literary star and could give Kappus a leg up in the world of poetry. Offering honest criticism to a friend is never easy, and neither is declining to do them a special favor. Maybe Kappus was too shy to follow up about his submission, and maybe Rilke agonized over how to let the young poet down easy.

After the lost letter of Aug. 30, 1908, Kappus replied on Nov. 25, 1908, and Rilke wrote back on Christmas Day of the same year. Kappus wrote his final letter to Rilke on Jan. 5, 1909.

Kappus asked an open-ended question in the final letter. He was feeling down on himself for taking some subpar writing assignments:

This work helps me get through the drab, gloomy hours and days that would otherwise remain empty. At first I started doing it to make money; later I kept up the habit, so I could feel I had at least done some work. Now I ask you, esteemed Mr. Rilke: Is that bad? Or can I cling to this as one more way to fence in my life with normal fixed obligations?

As far as we know, Rilke never answered in writing, despite living until 1926 (Kappus lived until 1966). The two didn’t have a falling out; Kappus thought of Rilke fondly and eventually published the letters that became Rilke’s most enduring work. Rilke just never responded.

In an afterword to the new edition of the Letters, Searls offers some light analysis of the long pause and the end of the poets’ correspondence:

Rilke’s “Lost Letter,” insofar as we can tell, and his last letter, from 1908, are noticeably cooler in tone than the rest, and there is no evidence of any continued contact between him and Kappus. Still, Rilke hadn’t cut off their connection entirely: his last address book, begun probably in 1918, contained an entry for “Kappus, Franz Xaver,” though no current address. The two men even ran into each other in the last year of Rilke’s life, in the summer of 1926, in the Swiss town of Ragaz, near Rilke’s last home, Chateau Muzot. Rilke was fifty, Kappus forty-three: no longer young poets.

Do I have the same valid excuses as Rainer Maria Rilke for my long gaps in correspondence? Yes and no.

While written correspondence has decreased in volume since the turn of the millennium (see graph below), the total volume of electronic communication eclipses what the postal service used to carry. One fuzzy estimate put the total number of email messages sent every day worldwide at around 205 billion.

Whether in a letter or an email or a text message, asynchronous communication has gaps by design. The recipient can sit with a message as long as they want.

Reading Rilke and Kappus’ florid apologies, I recognize some of my own tendencies. By the end, I found myself wanting them to cut out the groveling and simply respond when they were able. I thought they would both understand.

My frustration with Rilke and Kappus is the same as my frustration with myself. I would like to start apologizing less and replying more.

The new translation of Letters to a Young Poet is available to order via Bookshop (affiliate link). For more book recommendations, check out the Brutal South Bookshop page and the 2022 Weirdly Specific Holiday Book Guide.

Brutal South is a free weekly newsletter about class struggle and education in the American South. If you would like to support my work and get access to the complete archive of subscriber-only content, paid subscriptions are $5 a month.

Twitter // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts // Bookshop // Bandcamp