The persistence of false memory

Or, a tourist’s guide to racist propaganda

I stood in a cluster of middle fingers waving in the wind like reeds on the shore. We had cast our eyes skyward to a statue of John C. Calhoun, native son of South Carolina and ardent defender of the institution of chattel slavery.

We were standing in Marion Square three weeks ago protesting police brutality in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, but we had paused to acknowledge old Calhoun’s special place in hell and American history.

Hailing from a state with a majority-Black population, U.S. Senator and eventual Vice President Calhoun went a step beyond other apologists who defended slavery as a necessary evil. Responding to abolitionists who decried slavery as “sinful and odious,” Calhoun had this to say in an 1837 speech to the U.S. Senate:

I hold that in the present state of civilization, where two races of different origin, and distinguished by color, and other physical differences, as well as intellectual, are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding States between the two, is, instead of an evil, a good—a positive good.

As we marched and shouted through facemasks that evening, I occasionally heard the insect-hum of a drone flying overhead and imagined the scene from the sky. We were standing near the base of a 115-foot-tall Calhoun monument in a public square criss-crossed with dirt paths that bore a hardly-coincidental resemblance to the Confederate battle flag, on grounds once used for the drilling of slave patrols.

If the drone had shot up a few hundred feet for a wider view, it might have spied the other shrines to white supremacy peppering the city: The Confederate Defenders of Charleston statue by the Battery, featuring a buff nude man wielding a sword and shield. Hampton Park, named for the Reconstruction-era terrorist Wade Hampton. The streets and parks of Wraggborough, named to honor the family of slave trader Joseph Wragg. Charleston itself, named to honor King Charles II whose brother’s Royal African Company made a miserable fortune off the kidnapping and trafficking of African people into the slave-trading hub at Gadsden’s Wharf.

***

Charleston City Council voted unanimously Tuesday night to take the Calhoun statue down, finally. As I write this newsletter, a crew hired by the city is hard at work ripping Calhoun off his pedestal. Spectators brought out lawn chairs and watched all night as a crane wiggled the statue, as concrete dust and sparks flew from the top of the tower. It is taking some work to wrest it free.

The statue is coming down not due to any great courage on the part of the mayor or City Council members — who gave a full 105 minutes of grandiose speeches before voting — but because it had become politically untenable not to take action.

Echoing the removal of the Confederate flag from Statehouse grounds after the terrorist attack at Emanuel AME Church in 2015, the public shamed its representatives into making the barest concessions to human decency. Pardon me if I hold my applause for leaders who knew better, and could have done better, years ago.

Aside from the concrete and rebar, a thin veneer of manners and technicalities is all that keeps our country’s white supremacist propaganda in its place.

Here in South Carolina, the best-known technicality is a revision of the 1976 Heritage Act, passed as a compromise with white supremacists when the legislature took the Confederate flag off the Statehouse dome and onto the Statehouse grounds in 2000. As originally written in a House bill, the 2000 revision would have required a two-thirds vote by both sides of the legislature before a local government could remove or alter public memorials to “the Confederacy or the civil rights movement.” The final version removed the references to civil rights and instead added a comprehensive list of every war a South Carolinian ever fought.

City Council claimed authority to remove the Calhoun monument partly on a technicality: It isn’t a war statue, so state law doesn’t apply. But many of the racist shrines that remain, in our state and across the South, are the remnants of a concerted propaganda effort by groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who sought to represent the Confederate cause as noble and valiant.

In 2019, the Southern Poverty Law Center pulled together a painstaking account of 1,747 Confederate monuments, place names, and other symbols in public spaces across the country, writing:

Despite the well-documented history of the Civil War, legions of Southerners still cling to the myth of the Lost Cause as a noble endeavor fought to defend the region’s honor and its ability to govern itself in the face of Northern aggression. This deeply rooted but false narrative is the result of many decades of revisionism in the lore and even textbooks of the South that sought to create a more acceptable version of the region’s past. Confederate monuments and other symbols are very much a part of that effort.

***

I re-read the Heritage Act this week to confirm that it has no enforcement clause. It’s not at all clear what would happen if a city went rogue and simply trashed its Civil War participation trophies.

Individuals have done it before without consequence. At The Citadel, a public military college in Charleston, a chaplain quietly took down a Confederate flag that was displayed in the cadets’ chapel in August 2013, citing concerns about Black students and visitors who wanted to pray in peace.

“For me, the issue is not rewriting history,” retired Lt. Col. Joel Harris told me when I interviewed him. “It’s about placing certain icons in the appropriate venue.”

The flag’s disappearance went largely unnoticed until the white supremacist blog White Unity broke the news in September 2013, citing an unnamed cadet as a source. By the end of the month, facing pressure from alumni, the Confederate flag was displayed once again in the campus’s ecumenical house of worship.

Alumni and Black community leaders have applied public pressure to remove the flag from the chapel, but with no luck. The Citadel Board of Visitors voted 9-3 to remove the flag in 2015 but claimed their hands were tied by the Heritage Act. The flag is still there today with a security camera keeping watch over it.

There’s a petition going around to repeal the Heritage Act. I encourage you to sign it and follow the news at RepealTheHeritageAct.org.

In the meantime, I leave you with the opening lines of the poem “What It’s Like to Walk Under Shadows” by Asiah Mae and Charleston Poet Laureate Marcus Amaker:

There is a shadow that no one talks about

We allow it to reside among us in our supermarkets

In our schools

At festivals where willing ignorant laughter topples over the chatter of my ancestors’ unsettled spirits.

***

Thanks, as always, for reading. If you would like to support the Brutal South newsletter, you can become a paying subscriber for $5 a month. I have an extended podcast in the works for subscribers only later in the week, and I don’t think you’ll want to miss it.

Marcus Amaker has an excellent poetry collection out now called The Birth of All Things. I’ve been ruminating on his poems for a few weeks. You can order a copy from his online store.

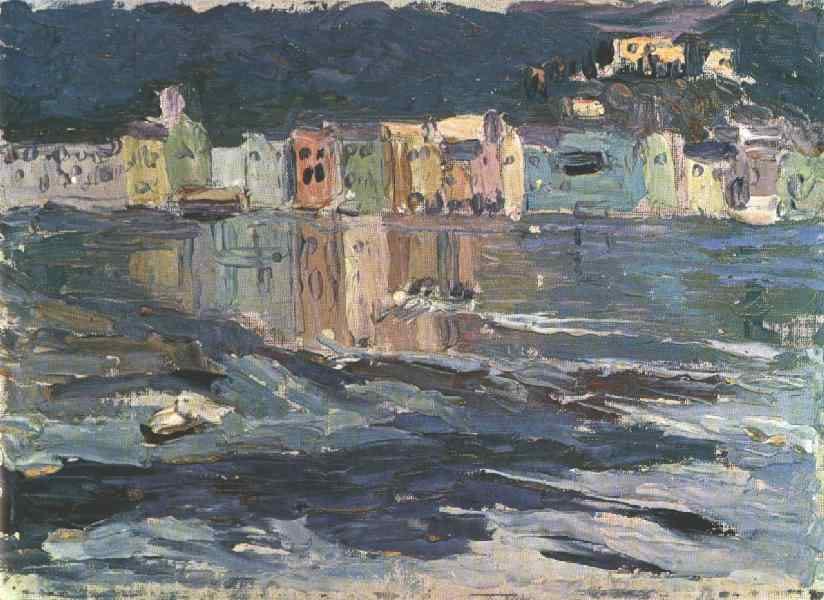

The painting at the top is “Santa Marguerite” (1906) by Wassily Kandinsky.