The horror of the land planarian

I just want to walk in the woods and gawk at nature with my kids

The sun was going down and my wife was building a fire by the shore of Lake Hartwell while the kids and I snooped around the campsite with flashlights.

One of the joys of camping with young children is that they are low to the ground and constantly finding weird specimens I would have otherwise missed. During our short walk to the campsite there in the far Appalachian corner of Oconee County, they had spotted two clusters of unfamiliar mushrooms and one of the girls had clapped a baby toad (Bufo americanus) between her cupped hands.

Now, after nightfall, my son turned over a fallen tree branch and we spotted something sickly yellow and glistening that was glommed onto the exposed wood. We stared as I held his hand to make sure he didn’t touch the thing. Maybe it was a slime mold, I thought out loud. Then it moved.

The thing was long and thin as a baby snake, with a flattened head like a hammerhead shark, and it writhed onto the dirt with the grace of a slug. We took a picture using the flash on my phone and watched as it dragged itself toward the shore.

My kids are inquisitive and drawn to the grotesque; they come by these qualities naturally. We try to encourage their questions when we’re out in the woods, even if (as is often the case) we don’t have satisfying answers. In this case I made a mental note to send my snapshot to Rudy Mancke, a beloved public-radio personality and naturalist who answers listener queries on the air every weekday morning during his Nature Notes segment.

Back at home, I did some googling and came up with a hypothesis about the thing we’d seen, and I sent an email to Mancke. He responded promptly:

As you supposed, that is the Land Planarian (Bipalium kewense), a Malaysian species that has been in the US for many years. They feed on earthworms mainly. The spade-shaped head and the flat, brown body are typical. It is also called the Terrestrial Flatworm. They probably got to the US in soil associated with ornamental plants. They range throughout SC.

I was fascinated and a little self-impressed at my educated guess. I did some more reading, and I bombarded my wife with each new horrifying detail I learned.

Here, for example, are some facts about Bipalium kewense from a write-up by Texas Master Gardener Eileen Linton:

A sticky mucus membrane on the lower side of the body secretes a slime helps them to move, much like a slug.

The head is usually shaped like a half-moon or arrowhead. There may even be eyespots present but the land planarian does not have actual eyes. Its mouth is located mid-way down the body (on its lower or ventral side) and its mouth also serves as its anus.

Land Planarians are not segmented like earthworms, but they do reproduce by fragmentation at the posterior end. The tip will attach itself to something in the soil, and the parent worm will pull away. The fragment is able to move immediately and will develop a head within 10 days. [emphasis mine]

Later I read how the land planarian will consume an earthworm by lying on top of it, trapping it in its mucus trail, and shooting its pharynx out of its mouth-anus to slurp the earthworm’s guts out.

I am trying to teach my children to think rationally about plants and animals, to think of them on their own terms rather than assign human qualities and morality to them. But some creatures test my limits. I felt a thrill of disgust at each new horrifying detail I learned about land planarians.

The book I think about most often when we’re hiking or camping is Annie Dillard’s 1974 transcendental nature memoir Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. Set in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains outside Roanoke, the book is based on Dillard’s own nature journals and independent research. The narrator goes on long walks by a creek and makes discursive observations about God and animals and the nature of suffering.

"I have to acknowledge,” Dillard wrote, “that the sea is a cup of death and the land is a stained altar stone. We the living are survivors huddled on flotsam, living on jetsam. We are escapees. We wake in terror, eat in hunger, sleep with a mouthful of blood."

I haven’t read the book in years, but I thumbed through it again last night thinking she might have mentioned land planarians at some point. They sounded like they’d be in her wheelhouse.

Sure enough, I found them in a chapter called “Fecundity,” which focused on the horrifying abundance of sentient life on earth:

The pressure of growth among animals is a kind of terrible hunger. These billions must eat in order to fuel their surge to sexual maturity so that they may pump out more billions of eggs. And what are the fish on the bed going to eat, but each other? There is a terrible innocence in the benumbed world of the lower animals, reducing life there to a universal chomp. Edwin Way Teale, in The Strange Lives of Familiar Insects—a book I couldn’t live without—describes several occasions of meals mouthed under the pressure of a hunger that knew no bounds ...

Planarians, which live in the duck pond, behave similarly. They are those dark laboratory flatworms that can regenerate themselves from almost any severed part. Arthur Koestler writes, “During the mating season the worms become cannibals, devouring everything alive that comes their way, including their own previously discarded tails which were in the process of growing a new head.”

I am trying to remind myself that the relationship between a planarian and its newly detached offspring is not necessarily analogous to the relationship between a human mother and child. But still. Think about it for a second.

Why did God tell Job to consider the Leviathan? Animals can be described but never fully comprehended. When I try to ascribe motives to living creatures, I am fully out of my depth. I can’t know the inner life of the planarian any more than I can know the inner life of another person, any more than I can know the mind of the almighty.

I live a fairly tamed life here in the city; I wander out into nature partly so I can feel small and overwhelmed again. My children are excellent guides in this respect. They are small people and often overwhelmed.

We experience the wild in different ways, though. I remember once when my wife and I stood stunned by an overlook on the Tallulah Gorge in Georgia, our kids were nonplussed and ready to keep walking. They wanted to catch beetles and look at the snakes in terrariums back at the welcome center. We were content to take in the big picture, while they wanted to lift up the world and peek at the underside.

***

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek is available via the nonfiction section of the Brutal South Bookshop page.

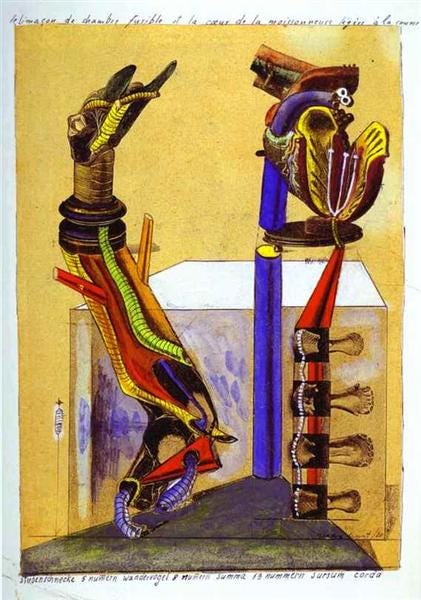

The image at the top is “The slug room” (1920) by Max Ernst.

Rudy Mancke didn’t take my question on the air, but I was looking through his radio show archives and saw that he answered another listener’s question about a land planarian back in July. You can listen to the episode here.

If you enjoyed this newsletter and you haven’t subscribed yet, consider signing up for $5 a month to receive subscriber-only content and access to the complete Brutal South archives.

As always, here’s where you can find me online:

Twitter // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts // Bookshop // Bandcamp

I enjoyed this on so many levels! From my own childhood to an aquarium filled with snails in my classroom that my students observed “hugging” each other. My grandson and I were preparing soil in the garden and unearthed a worm snake. It was beautiful in color. We both just stared and breathed in the scent of freshly turned soil in amazement.

Ha, I love planarians, lil weirdos. For a couple years my msn messenger screen name was "Turbellaria" and a friend was disappointed to find out it wasn't a fantasy princess name (though it totally could be!)