Singing a weird song of death

Reading Faulkner and a Japanese survivor poet on the anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing

When I was a boy I tried to imagine hell, and then I went to school and learned about the Second World War, and I tried to imagine the Japanese city of Hiroshima in the moments after my country dropped an atomic bomb on it and slaughtered 90,000 people.

And I still can’t imagine hell, and I still don’t understand Hiroshima or Nagasaki or for that matter Dresden in the hours of their destruction, but I still try. Every year on August 6, I read a few poems by Kurihara Sadako, a Japanese poet from Hiroshima who was at home two-and-a-half miles from ground zero when the bomb went off in 1945.

Sadako published her first poem in 1930, when she was 17 years old, in the Hiroshima newspaper Chugoku Shimbun. She is best known for the poems she wrote later in life after becoming an adult, watching her country go to war for a cause she despised, and watching a foreign power reduce her hometown to a “socket without an eyeball,” as she wrote in the 1952 poem “Ruins.” She went on:

Bred in the pulpy entrails and putrid flesh

of our dead,

white larvae grow fat on bloody pus,

cling to the rubble.

Shoo, fly! Shoo, fly! But they don’t shoo.

Most of her poems are hard to find translated into English, in part because the Civil Censorship Detachment blocked their publication during the Allied occupation of her country. A thin volume of translated poems, When We Say Hiroshima, includes an image of a 1946 proof page that censors marked out in its entirety.

It is cliche by now to note that the victors of war write the history books. Some historians now believe that U.S. President Harry Truman had little to do with the decision to drop the bomb on those two cities full of civilians; his most important contribution may have been signing off on the press release about why we did it.

Sadako, for her part, dedicated the rest of her life to ripping up the propaganda of warmongers, abroad and in her own country.

Here is a portion of “What is War?” — a poem the censors didn’t want you to read:

And I abhor those blackhearted people

who, not involved directly themselves,

constantly glorify war and fan its flames.

What is it that takes place

when people say “holy war,” “just war”?

Murder. Arson. Rape. Theft.

The women who can’t flee take off their skirts before the enemy troops

and beg for mercy — do they not?

I am sure these poems lost some of their power in translation, but still some phrases arrested me when I read them yesterday, like when she wrote that the blackened trunks of trees “sing a weird song of death” (“Reconstruction,” January 1946). It’s a song worth hearing.

***

The Mississippi man of letters William Faulkner wrote about the destruction of the American South during the Civil War. His portrayal of scorched earth and ravaged homes in the 1938 novel The Unvanquished was as unsparing as Sadako’s.

He wrote about doom, decay, and dispossession, albeit in slower motion than the blast of an atom bomb:

“Because wars are wars: the same exploding powder when there was powder, the same thrust and parry of iron when there was not — one tale, one telling, the same as the next or the one before.”

In the years after World War II, Faulkner gained a following in Japan. This can be partly attributed to his general celebrity after he won the 1949 Nobel Prize in Literature. His acceptance speech in Stockholm may have meant something to the families of the victims of war.

“There are no longer problems of the spirit,” he told the crowd in the banquet hall. “There is only the question: When will I be blown up?”

Faulkner’s work resonated in Japan after the war during that country’s own reconstruction. In 1955, as an act of cultural diplomacy, the U.S. Information Service sent Faulkner on a junket to the mountain resort town of Nagano, where Japanese literati and professors received him as a celebrity.

I have been trying to track down a transcript of the lectures he gave in Nagano, but have not had any luck. I want to believe he brought inspiration and uplift to the assembled crowd, but I am not so sure. Contemporary accounts by U.S. public affairs officers suggest that he was stumbling drunk for much of his time in Japan, brought low by his disease of alcoholism. Various functionaries and assistants had to physically hoist him out of chairs and keep him functioning with heavy doses of liquor.

Faulkner fared poorly in the limelight, and maybe he felt some self-pity about it. Near the end of The Unvanquished, he wrote in the voice of his narrator,

“I realised then the immitigable chasm between all life and all print — that those who can, do, those who cannot and suffer enough because they can’t, write about it.”

The end of Faulkner’s life was tragic. But do you know who mitigated that chasm “between all life and all print”? Kurihara Sadako.

***

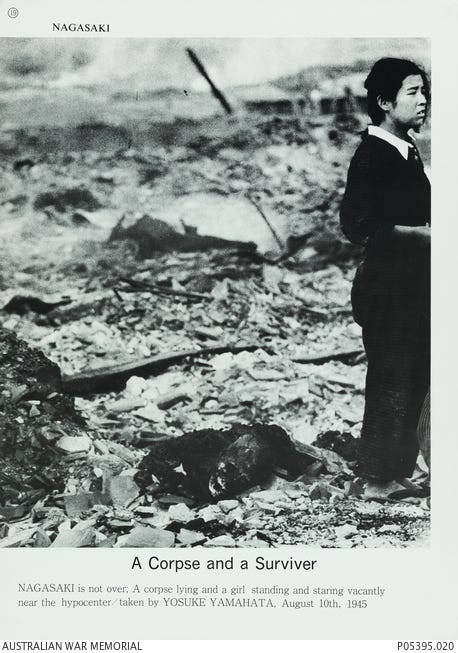

The Japanese have a word for survivors who bore witness to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: hibakusha. Kurihara Sadako wore that mantle with a dignity and endurance I can barely fathom.

Because she wasn’t only a poet. She was a lifelong activist.

She played a vital role in the political career of her husband, a committed leftist who served 12 years in Hiroshima’s prefectural assembly starting in 1955. She wrote poems taking her own country to task for pursuing a nuclear arsenal, for playing the aggressor in the Pacific War, and for embracing a resurgent nationalism after the war.

She won a few literary awards and used her acceptance speeches to speak truth to power. Here she is in 1990, receiving the third Tanimoto Kiyoshi Prize:

The dropping of the atomic bomb, a crime against international law, is intolerable. But flat-out denying historical fact — saying that there was no rape of Nanking, that the Chinese dreamed it up — and then on top of that bringing in America’s dropping of the atomic bomb in order to absolve Japan of guilt as victimizer: that is to use Japan’s hibakusha to advance one’s argument through sheer force. The hibakusha of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are mortified.

There are still problems of the spirit, and as for the open question of when we will all be blown up — it lingers. But when I consider the potential for hell in a world still bristling with nuclear warheads, I remember a line from The Unvanquished and consider how it prophesied the courage of people like Kurihara Sadako:

“...this was it — the regret and grief, the despair out of which the tragic mute insensitive bones stand up that can bear anything, anything.”

Kurihara Sadako died at home in 2005, at age 92. Her words are worth reading today or any day.

***

When We Say Hiroshima: Selected Poems is available from University of Michigan Press for $14. The introduction by translator Richard H. Minear was helpful in the writing of this essay.

One of Kurihara Sadako’s best-known poems is “Let us be midwives!” It is beautiful, and you can read it here for free.