Save South Carolina schools, for Robert Smalls’ sake

How a daring act of liberation paved the way for free public schools in the Deep South

When Robert and Hannah Smalls planned their escape from the slave state of South Carolina in May 1862, they did it to liberate their 4-year-old daughter Elizabeth and their infant son Robert Jr.

“It is a risk, dear, but you and I and our little ones must be free,” Hannah told her husband, according to Cate Lineberry’s 2017 book Be Free or Die.

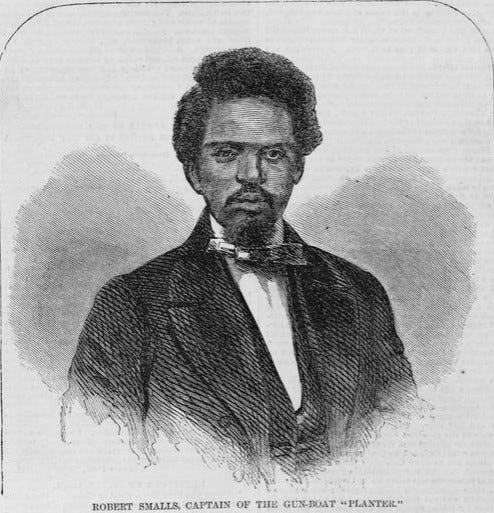

Robert Smalls’ commandeering of a Confederate steamship is one of the great stories of personal liberation in my state’s history. Today I wanted to consider that story’s connection to broader liberative politics, particularly in the field of education.

Under the conditions of chattel slavery, Elizabeth and Robert Jr. could be torn from their parents’ arms at any time and sold away at the market. Enslaved children were forbidden to learn to read and write, while their wealthy white peers received private schooling. (The children of poor white families were mostly locked out of a formal education as well.) Surrounded by the debauched wealth of the port city of Charleston, they were forbidden to take their share.

It was under these conditions that Robert and Hannah Smalls decided to win freedom or die trying.

Robert, 23, was working on a Confederate sidewheel steamer called the Planter. He had convinced the other black crewmembers to steal the ship in the middle of the night, take it past Confederate sentries and fortifications on the Cooper River, and pick up his family and other escapees from another ship on the way out to the harbor. Their destination was the Union blockade, roughly 10 miles out.

They would do it all on a noisy steamer belching smoke, in a militarized city that had started a civil war. If they were caught, they faced certain death.

Easing out from the wharf that night, they flew the “Stars and Bars” Confederate flag and the South Carolina state flag. Smalls donned the captain’s straw hat, hoping to pass as a white man under the cover of night. He had learned the whistle signal that sentries used as a security code: two long blows and a short one.

“Blow the damned Yankees to hell, or bring one of them in,” a sentry yelled from shore as they sailed by.

“Aye, aye,” Smalls said, according to Lineberry’s book.

Out on the dark waters approaching the Union blockade, they hoisted a white bedsheet in surrender, turning over the ship and a stockpile of Confederate guns.

Robert Smalls had won his family’s freedom, but he didn’t rest there. He served in the Union Navy and helped convince Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to let other black men fight for the cause.

After the war, Smalls returned home to Beaufort, S.C., where he used his prize money from seizing the Planter to buy his dead master’s mansion. He opened a general store for freedmen, edited the Beaufort Southern Standard, and won election to the state legislature.

At a time when Republicans were pushing for a progressive reconstruction of the American South, Smalls founded the Republican Party of South Carolina. Shortly after taking office alongside other black lawmakers including Joseph Hayne Rainey, he served as a delegate to craft the state’s progressive 1868 constitution.

***

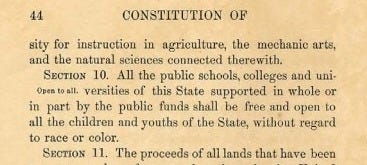

The new constitution was radical for its time, reflecting the ascendant power of Smalls’ Republican Party.

It abolished debtors’ prisons, removed property ownership as a requirement for elected office, and granted new rights to women. And it guaranteed that all South Carolina’s children — black and white, rich and poor — could attend “a liberal and uniform system of free public schools.”

Black civic leaders, the Freedmen’s Bureau, and Northern philanthropic groups had established successful private schools for black children before 1868. The new constitution sought to build on that foundation and make progress permanent.

When Reconstruction ended in South Carolina with Wade Hampton’s gubernatorial election in 1876, the early glimpses of progress began to grow dim. Democratic politicians, appealing to aggrieved white Southerners across class lines, began clawing back at progress almost immediately.

The state continued to fund schools for black students, but it funded them poorly. The University of South Carolina, which had admitted its first black student in 1873, closed its doors in 1877 and re-opened as an all-white agricultural college in 1880. Meanwhile white supremacist gangs with names like the Red Shirts began assassinating black politicians and intimidating black voters across the state.

The 1895 constitution, the brainchild of the white terrorist “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman, laid the framework for Jim Crow laws, disenfranchisement of black voters, and the further abandonment of “liberal and uniform” education as an ideal.

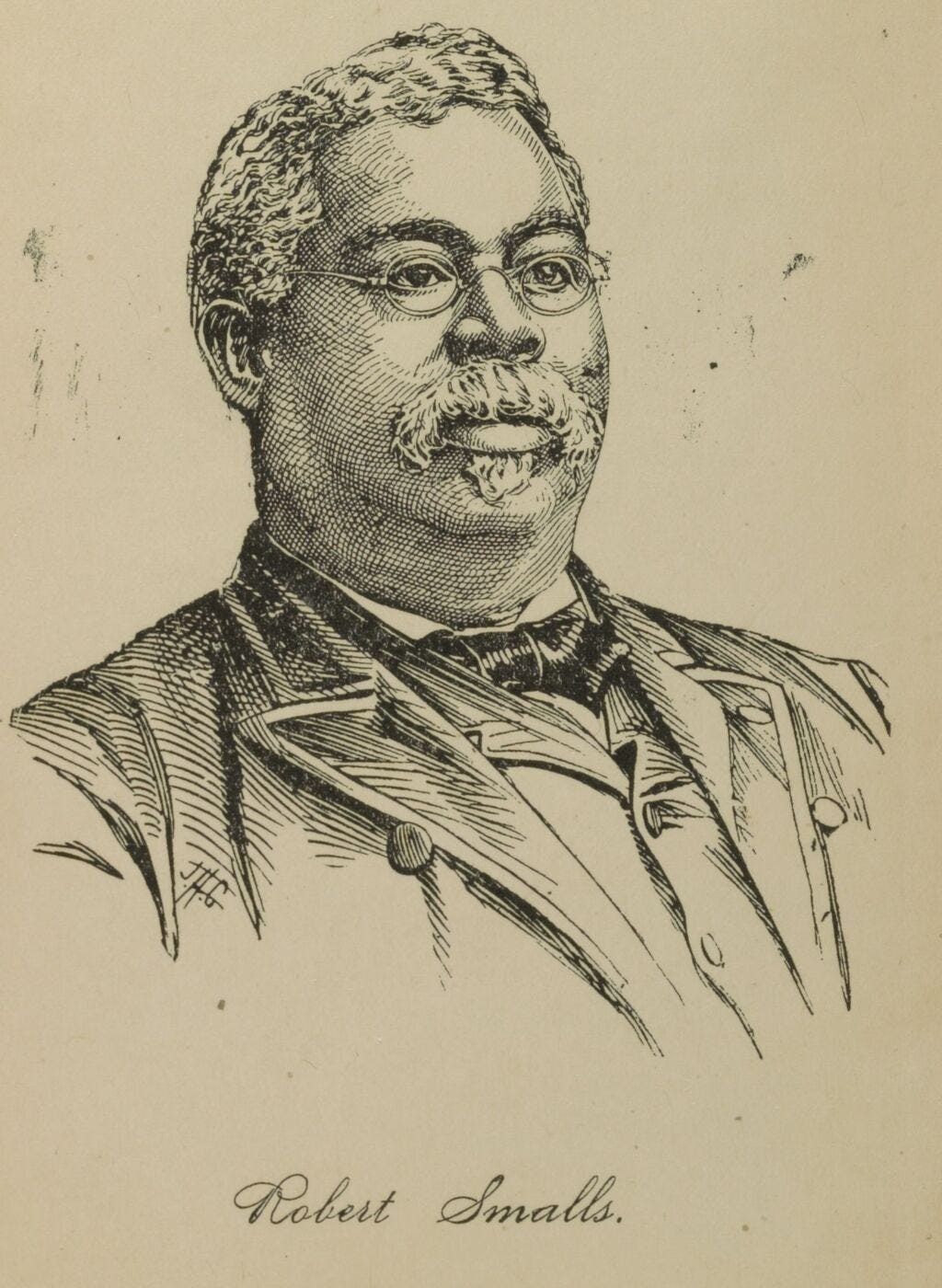

Smalls, who had by then served as a Congressman, returned to the Statehouse for the 1895 constitutional convention. Where once he had pushed the envelope for positive change, now he found himself fighting tooth and nail just to preserve black men’s right to vote. He predicted, accurately, that dark times and economic woes lay ahead for South Carolina if it went down this path.

“I appeal to the gentleman from Edgefield to realize that he is not making a law for one set of men. Some morning you may wake up to find that the bone and sinew of your country is gone,” Smalls said. “The negro is needed in the cotton fields and in the low country rice fields, and if you impose too hard conditions upon the negro in this State there will be nothing else for him to do but to leave.”

***

The history of our schools ever since has been defined by struggle. Every major step toward equity has been meticulously whittled down by conservative lawmakers and local school boards.

The separate schools were unequal from the start. By the mid-20th century, the gap was blatant: In Clarendon County during the 1949-50 school year, for example, the district spent $179 per white child and $43 per black child. Clarendon County was the launching point of Briggs v. Elliot, a court case that was eventually folded into Brown v. Board of Education, the court case that officially overturned the judicial standard of “separate but equal” schools nationwide.

But after Brown and the official end of segregated schools, South Carolina’s white parents, politicians, and school board members found ways to skirt the law. A crop of private “segregation academies” for white children popped up across the state, and the careful drawing of district and school attendance lines allowed for a rapid re-segregation of the public schools by race and family income. And a fundamentally inequitable school funding system left schools in poorer rural areas to molder and decay.

Heading into the 21st century, the resurgent South Carolina Republican Party was no longer recognizable as the “party of Lincoln,” as Robert Smalls liked to call it. It clinched control of every branch of state government in 2003 and set about methodically dismantling public education funding.

Their most common tactic: Make promises on paper, and then simply refuse to follow through on funding those promises. It would almost be funny if it weren’t so cruel.

Classroom size limits? The state stopped enforcing them in 2010, allowing classroom sizes to rise as teachers took on untenable workloads.

Annual teacher raises? The legislature reneged on that promise during the Great Recession and still has not made up for the lost wages.

Replacing old school buses? They passed a law to phase out the most dangerous buses in 2007 — and decided not to fund that promise for seven of the following nine years. The legislature only scrounged up some one-time money for the project in 2019 after a series of horrifying bus fires made front-page news across the state.

All those broken promises add up. As of 2018, the state education budget was shortchanging the state’s own school funding formula by nearly a half billion dollars per year.

Today our schools rank last or near-last on most measures of academic achievement. Teachers are quitting in droves early in their careers, demoralized by incoherent leadership, unworkable conditions, and unlivable pay. The clawback of progress is hurting us all.

***

South Carolina’s schools are a far cry from the “liberal and uniform” ideal that Robert Smalls’ constitution envisioned. The current constitutional standard, as established by a 1999 Supreme Court ruling, is that the state must provide a “minimally adequate” education.

(The court found in 2014 that the state was failing to meet even that low bar. Following a familiar pattern, the legislature ignored the ruling and installed new judges who dropped enforcement of the ruling in 2017.)

It’s only been 151 years since the 1868 constitution, and just 49 years since South Carolina eliminated explicit race-based segregation. Reactionary elites have attempted to thwart progress at every step along the way, and they continue to do so.

History shows that South Carolina’s ruling class can be brought to heel. One method for doing this was federal coercion, which unfortunately does not appear to be a tool at our disposal today.

The other method is mass humiliation. The governor promised to seek a modest raise for teachers in the 2020 legislative session after an unprecedented 10,000 educators and supporters marched on the Statehouse in May 2019 chanting, “We teach, we vote.” The teacher group SC for Ed has more demands, and its members have been watching legislative hearings like a hawk. They give me hope.

Public shaming has worked before. Well-organized teachers shamed the Democratic legislature into funding full-day kindergarten in the ‘90s. Public outcry and pictures of flaming school buses shamed the Republican legislature into replacing old buses in 2019.

Sometimes the pressure has to be intense and personal: In 2016, I sat in a school board meeting and watched as children, parents, and the mayor of Charleston shamed the Charleston County School Board into replacing a decrepit building for a majority-black elementary school.

We can humiliate them at the polls or we can humiliate them in the court of public opinion. Either way, we need a win this year. Do it for the kids. Do it for Robert Smalls. Do it for the cause of liberation.

***

I graduated from South Carolina public schools, and my children attend them now. I covered education as a daily news reporter in my state for three-and-a-half years. If you’d like to read some of my previous newsletters on education, check out this one about the University of South Carolina’s innovation in the field of racist admissions or this one about the 2019 teacher labor movement in K-12 schools.

If you’ve enjoyed this week’s issue, hit that Subscribe button to get something new in your inbox every Wednesday. Consider supporting my work for $5 a month (learn more about that here if you’re interested). Or if you just want to spread the word, hit the Share button below. Thanks!

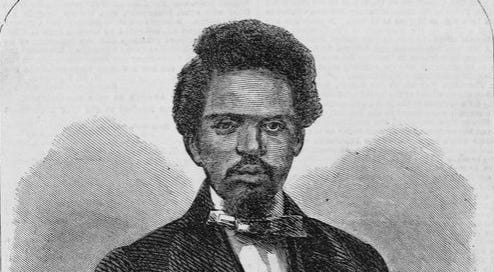

The illustrations in this week’s issue come from the following sources:

Robert Smalls, captain of the gun-boat "Planter.” Illus. in: Harper's weekly, v. 6, 1862 June 14, p. 372. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

Smalls, Robert, Sarah V Smalls, and Daniel Murray Pamphlet Collection. Speeches at the Constitutional Convention. Charleston, S.C.: Enquirer Print, 1896. PDF. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.