I live in a small town and I want to tell you how small it is.

There’s a bar in an old bait shop across the river that hosts punk shows from time to time. A friend from high school was playing a set there, and he asked me to play a few of my songs as a novelty solo act. I said sure.

By the time I arrived at the bar, I had googled my friend’s band, and one name stuck out from the lineup. The singer was a guy who’d written me an impassioned email several years earlier because I offended him with something I did at my day job.

I was writing for the daily newspaper in town, an institution that has been around for so long that its editorial board prodded South Carolina’s politicians to secede from the United States of America in 1860.

The thing I did that offended this singer was that I wrote a story about hazing at his alma mater, the local military college, which has been around for so long that it supplied the Confederate soldiers who fired some of the first shots of the civil war that baptized our state in blood and fire.

I had replied to him, as was my custom at the time, and I think we ended up talking on the phone about it. He was a reasonable guy, but I don’t think I won him over.

So anyway I knew walking into the bar that there might be some awkward silences, and I warned my friend that this might be the case. And I went right up to the singer and introduced myself, not sure if he’d remember who I was. He remembered. We shook hands and made peace and had a little banter. Southern manners won out, I guess.

Then the singer’s partner walked over, and she remembered me too. I wasn’t prepared for this.

Turns out she used to work in the leasing office at an apartment complex I’d written about where two people fell out of upper-floor balconies in the space of three months. One was seriously injured; one died; I was there to figure out what was going on. She remembered me because it was her duty on that day to turn me away with a polite No Comment.

She said she wasn’t mad about it, and I made no apology. Still, I felt the tension of our small talk ratchet up another notch. I played my songs and stuck around for their set and scooted home soon thereafter.

***

There are different schools of thought about what journalists should do with angry phone calls and emails. I have spent time in each school and still don’t know what to tell you.

One editor advised me to respond as briefly as possible, thank the reader for their feedback, and leave it at that. I tried that for a while but it gave me no satisfaction. I doubt my critics were satisfied, either. Especially in writing, a phrase as simple as “Thank you for your constructive criticism” seemed to drip sarcasm.

Another common approach is to simply delete those emails and voicemails, take a Prozac and shake it off. It’s a corollary to one of the earliest internet aphorisms, “Never read the comments.” I have done this too, sometimes out of necessity because I can’t spend half my workday responding to people who put the word “journalist” in scare quotes.

Then there is the hard path: Respond to all of them, every last one. Defend your profession. Concede on points where you could have done better. This can be a form of self-flagellation or self-righteousness if you let it be, or it can occasionally bear fruit.

I wrote several difficult stories over the years about that military college, whose alumni were rarely shy about sharing their opinions on my reporting. Some of them were perfectly thoughtful people; others just wanted to drop me a quick note and say they hated my guts. I didn’t waste time responding to insults or vague threats, but if they offered real criticisms of my work, I tried to distance myself emotionally and take an honest look at my article from their point of view.

After my phone call with the singer, I ended up writing a follow-up story about the school’s alumni rising to its defense. Several of the people I quoted were my harshest critics. I am not telling you this to make you think I am some saint. I was just trying to listen.

***

There are certain messages that no one needs to dignify: racist and misogynist attacks, threats of violence, off-topic faxes from the terminally lonely.

The American journalists I have known are a little flinty these days, partly because the president brands us as “enemies of the people” and encourages his followers to join him in a dream world narrated by cable-TV sycophants. It’s partly because we’re struggling to pay the bills while our readers accuse us of being out-of-touch elitists. But our defensive stance is also timeless.

When a man with a shotgun killed five workers at a newsroom in Maryland in June 2018, his grievances had little to do with the national political climate. The newspaper had run an article about the accused gunman harassing a former high school classmate via social media. He had tried suing for defamation, but a judge had dismissed the suit.

Survivors from the Capital Gazette newsroom say they saw a veteran newspaperwoman, Wendi Winters, stand up and charge the shooter with a trash can, buying them enough time to run for cover. She died saving her colleagues.

For a lot of us working at local news outlets, we read the news and considered whether we would show such courage in the face of death. Some of us made mental lists of our top five most likely assassins.

To be sure, American journalists are safer than our peers in Turkey, China, Egypt, or any of the other countries that topped the latest rankings for journalist imprisonment according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. I don’t have half the courage of Jamal Khashoggi, Emilio Gutierrez Soto, Wa Lone, or Kyaw Soe Oo.

But you do grow thick skin. You do take calculated risks. I recently read about Tom Fox, a Dallas Morning News photographer, who hid behind a courthouse alcove during an active shooting and managed to capture a head-on photograph of the gunman leaving the building. It’s the job.

***

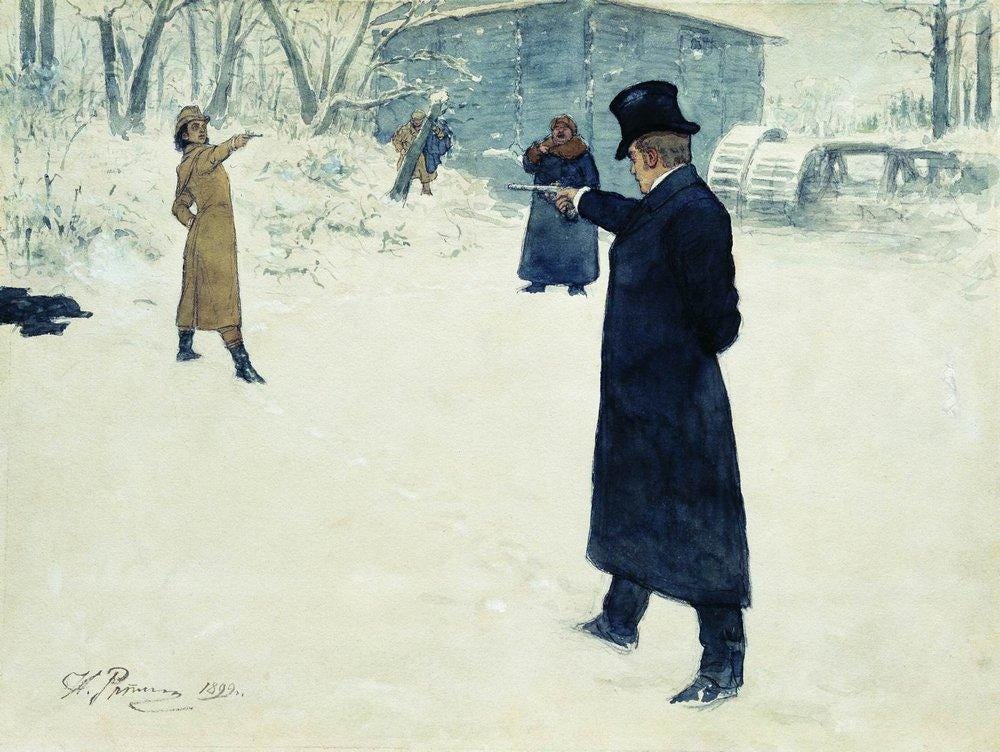

The newspaper I wrote for is so old, it used to publish announcements of gun duels. These were not spur-of-the-moment street fights; they were carefully choreographed and overseen by referees.

The proceedings always began with one gentleman alleging that another gentleman had besmirched his honor, and the adversaries would often negotiate the terms of their duel in a special section of the paper over the course of months. The idiocy of chivalric gun combat began with words on paper, like a want ad for blood.

Knowing the power of words, I was rarely flippant about my hate mail. I learned in time to control my defensive response and winnow out the feedback that could make me a better reporter, but I was never able to shrug off the avalanches of scorn that came my way.

Vindication was rare but sweet. One time when a reader called me a dickhead in an email, I wrote back asking if he had any specific criticisms or factual corrections to offer. He called me on the phone almost immediately and sounded a little bashful.

“Yeah, I’m the guy who called you a dickhead … Sorry about that,” he said. We talked it over for a few minutes and even had a good laugh about it. I don’t think we ever spoke again.

When I say my town is small, I am talking about a feeling, not a headcount. Strictly speaking, I live in a city of 100,000 some-odd people and go to work in a city of 130,000.

The smallness of my town makes it difficult to burn a bridge. The mayor who preemptively trashed my reporting about him in a Facebook video lives right down the street where my kids go trick-or-treating on Halloween. I have offended some dear friends with my reporting and had to make slow, careful amends to save our relationship.

When the hate comes, it usually comes from a stranger. There is perhaps something to be said for the hard approach of responding to every critique: When it’s all said and done, we aren’t strangers anymore. But I can’t say for sure whether it’s better to pursue inner peace or interpersonal peace. Some days you have to pick one.

***

The watercolor painting at the top of the page is Ilya Repin’s 1899 depiction of the fictional gun duel between Eugene Onegin and Vladimir Lensky.