Marked for death

Bearing witness to executions in Missouri, Alabama, and Oklahoma

In the month of October, the states of Missouri and Alabama executed two intellectually disabled men.

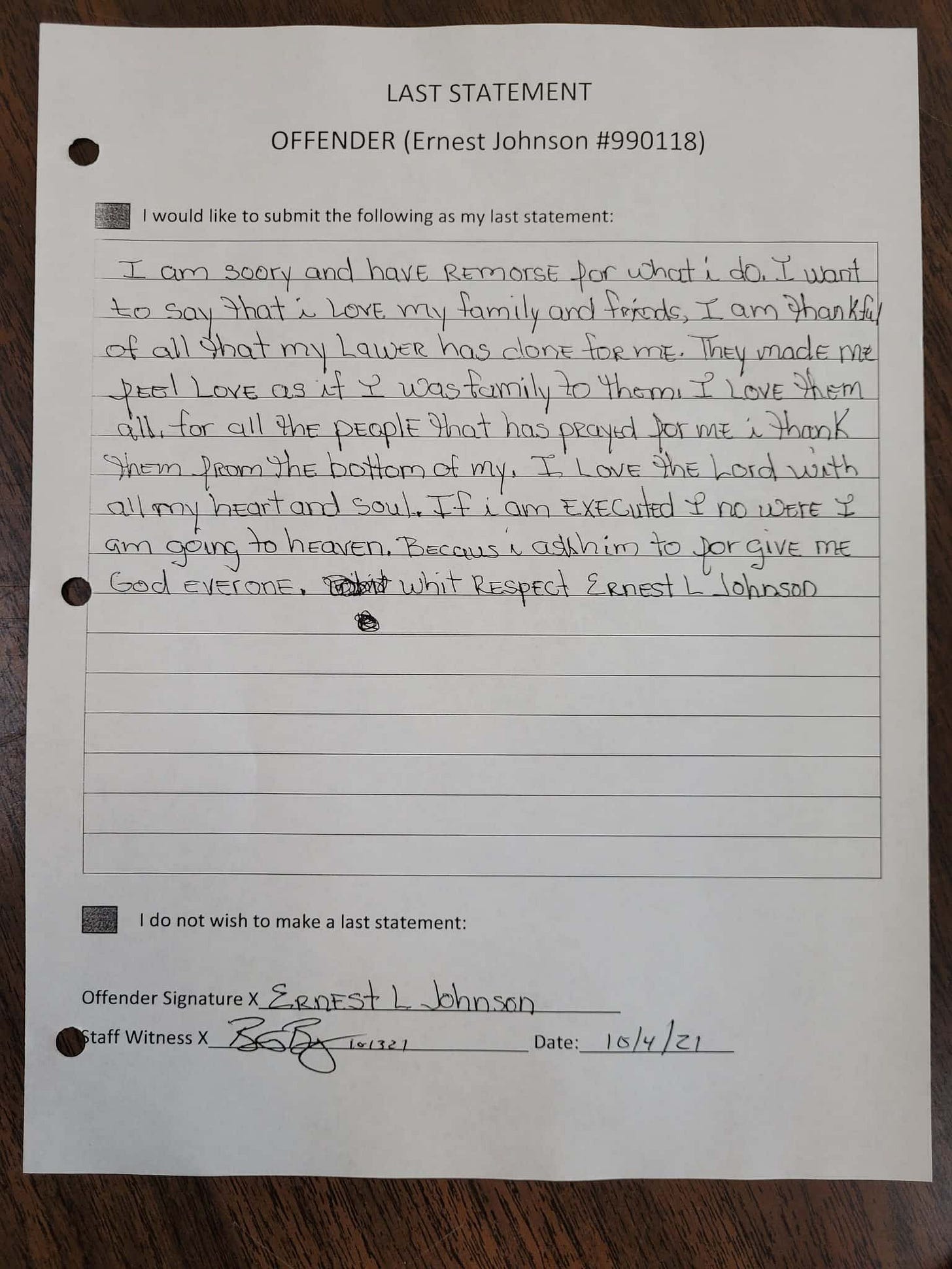

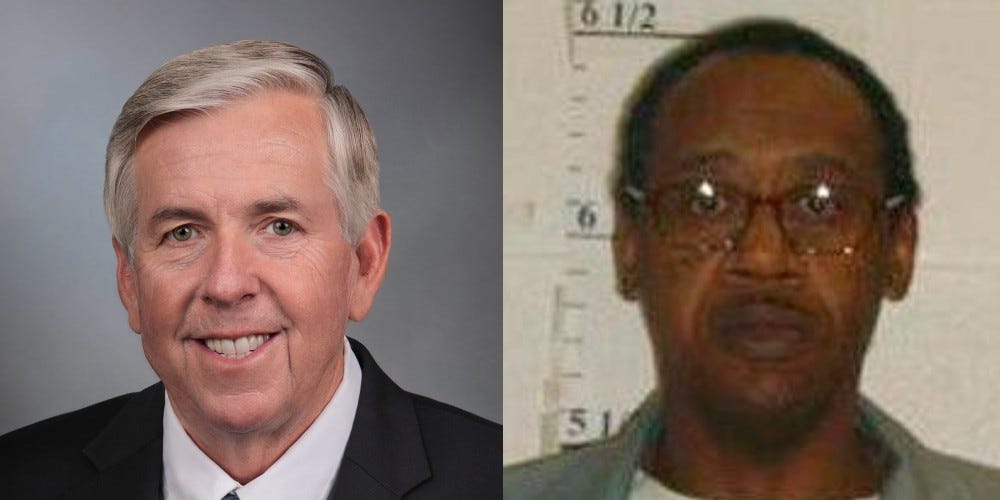

Missouri Gov. Mike Parson’s victim was Ernest Lee Johnson, a 61-year-old Black man born with fetal alcohol syndrome. Johnson was put to death for killing three people with a claw hammer during a convenience store robbery in 1994.

“He silently mouthed words to relatives as the process began,” wrote Associated Press reporter Jim Salter, who witnessed Johnson’s lethal injection on Oct. 5. “His breathing became labored, he puffed out his cheeks, then swallowed hard.”

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey’s victim was Willie B. Smith III, a 52-year-old Black man with an IQ somewhere between 64 and 75. In 1991, Smith abducted Sharma Ruth Johnson at an ATM, withdrew money from the machine using her card, and then took her to a cemetery and shot her with a shotgun.

Pastor Robert Wiley prayed with Smith and put his hand on Smith’s leg as an official injected him with the lethal drug cocktail on Oct. 21.

“Smith appeared to quickly jerk twice upward on the gurney as the first drugs hit his system,” reported the AP’s Kim Chandler. “‘That’s the midazolam,’ one of his attorneys said … His breathing was initially labored, but then slowed and stopped.”

Application of the death penalty in the United States is arbitrary, capricious, and infamously racist. In murder cases, the race of the perpetrator and the race of the victim are among the best predictors of whether the state will mark a defendant for death. Johnson and Smith were both Black men, like a disproportionate share of the people executed by the United States from Jim Crow to the present day. One of Johnson’s victims was a white woman; Smith’s victim was a white woman and the sister of a police officer.

These executions have several handmaidens, not least among them the members of the U.S. Supreme Court’s liberal wing who drew the exact loopholes they knew states like Missouri and Alabama would use. The court held in Atkins v. Virginia (2002) that it is unconstitutional to impose the death penalty on people with intellectual disabilities, but it allowed states to decide what counts as intellectual disability (3 conservative justices dissented, desiring to put no limits at all on executions for the intellectually disabled). Hall v. Florida (2014) made it harder to prove intellectual disability in capital punishment cases.

In Johnson and Smith’s death penalty cases, there were last-ditch efforts to appeal to a higher authority than the court. Pope Francis sent a message to the Missouri governor pleading for Johnson’s life, to no avail.

“This request is not based upon the facts and circumstances of his crimes; who could not argue that grave crimes such as his deserve grave punishments,” wrote Archbishop Christophe Pierre, the Vatican’s ambassador to the United States, in a Sept. 27 letter on Francis’ behalf. “Nor is this request based solely upon Mr. Johnson’s doubtful intellectual capacity. Rather, His Holiness wishes to place before you the simple fact of Mr. Johnson’s humanity and the sacredness of all human life.”

Missouri’s governor didn’t relent, and neither did Alabama’s. In fact, the state of Alabama wouldn’t even allow Smith to have his own pastor present at his original execution date on Feb. 11, setting off an appeal that delayed the execution by 8 months. The Supreme Court upheld an injunction against the state, allowing Smith’s pastor to enter the death chamber and the execution to proceed on Oct. 22.

The next execution is set for tomorrow, Oct. 28, in Oklahoma. It will be the state’s first attempt at killing someone by lethal injection since it botched a pair of executions in 2014 and 2015. The victim of the 2014 botched execution, Clayton Lockett, moaned and writhed for 40 minutes before dying.

The state of Oklahoma has seven execution dates scheduled after a 6-year hiatus. First, on Thursday, it aims to kill John Marion Grant, who was convicted of murdering a prison cafeteria worker in 1998.

If Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt cared to hear an extreme case for clemency based on personal circumstances, rather than a universal appeal to the worth of human life, he could listen to Grant’s story and have mercy.

Grant, who was neglected and abused as a child by his single mother, started stealing food and clothes for his siblings at age 9 and was shunted into the juvenile justice system at age 12, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. He was placed in a state-run facility known as the Oklahoma Shame, notorious for its whippings, rapes, and assaults. After briefly re-entering society, he entered the adult prison system at age 17 after being arrested for armed robbery.

“John Grant never had a chance,” Grant’s attorney Sarah Jernigan said in a final appeal to the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board. The board voted 3-2 to let the execution proceed.

A man who lived most of his life in a cage is about to be put to death in a cage. Others will follow, unless and until we end the practice of state killing.

Next on death row in Oklahoma is Julius Jones, who has spent half his life in prison for a murder that he says he did not commit. His lethal injection is set for Nov. 18, despite considerable evidence that he is innocent.

The wealthiest and most powerful country on earth has used its wealth and power to construct an elaborate system for warehousing and disposing of human beings. The architects of its death chambers include respected politicians as well as amateur electricians and Holocaust deniers. States including Alabama are in the process of building gas chambers, and Arizona, whose most famous sheriff once bragged about his open-air concentration camps for migrants, has even tried to manufacture Zyklon B, the Third Reich’s poison of choice.

Executions, on the whole, are in decline, and these might be the final days for a brutal vision of justice. I hope so. But that fact is no comfort to the men we are preparing to kill.

***

For a list of scheduled executions by state, see the Death Penalty Information Center. To get involved with the fight against the death penalty in your state, visit deathpenaltyaction.org.

Here in South Carolina, executions are on hold while the state figures out how to assemble a firing squad. The state has run out of lethal injection drugs since companies stopped selling them for the purposes of killing people, but it still maintains a 109-year-old electric chair in its death chamber.

If you would like to ask an important question, email the South Carolina Department of Corrections and politely ask whether the state is still using the electric chair helmet it bought from the self-taught electrician and Holocaust denier Fred A. Leuchter Jr. I put in a Freedom of Information Act request on this subject, but the Department of Corrections claimed an exemption for records related to “security plans and devices.”

In lighter news, I have two new podcast episodes coming soon. Check out the Brutal South podcast on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Twitter // Bookshop // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts

Smith's own mental health expert said he wasn't intellectually disabled.