It’s 10 p.m. Do you know where your attorney general is?

Checking in on South Carolina’s defender of the indefensible

South Carolinians were reminded last week that we have an elected attorney general and that his legal actions are, at times, incompatible with human life and well-being.

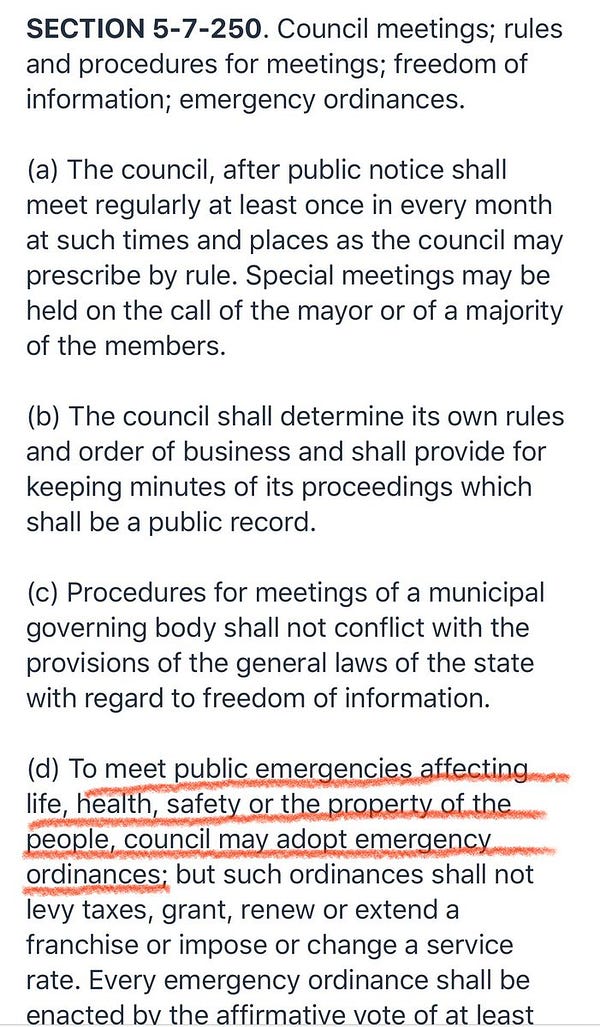

In the absence of state-level action to prevent the spread of COVID-19, several local governments enacted their own stay-at-home ordinances and ordered some businesses to close. Folly Beach, an island community that’s popular with spring breakers, set up police checkpoints on the access road and began only allowing locals through.

But on Friday, March 27, South Carolina Attorney General Alan Wilson’s office released a legal opinion threatening municipal governments with lawsuits for taking emergency action.

“Only the governor can order stay-at-home-ordinances, and local governments could face legal action if they enact and enforce those orders,” said Wilson, a Republican. He based his legal opinion on shaky precedent and previous governors’ executive actions during hurricane season; sharper legal minds quickly poked holes in his argument.

An attorney general’s opinion is not enforceable and does not set court precedent in South Carolina. But the threat was enough. Folly Beach walked back its rule just in time for an onslaught of weekend visitors, and wary South Carolinians watched in horror Saturday as hundreds of people packed the beach in close clusters, flagrantly ignoring social-distancing guidelines. Locals held signs in protest along the roadway begging visitors to turn back.

Folly Beach officials reinstated the ban in an emergency meeting Saturday evening, lawsuits be damned. Damage was already done.

Since South Carolina Governor Foghorn Leghorn finally announced an emergency shutdown of nonessential businesses Tuesday, the news cycle has moved on. (As of this publication on April 1, the governor still has not issued a shelter-at-home order.) But I wanted to take the time to dwell on Wilson’s uniquely dumb legacy from nine years in office — and encourage you to take a look at your state’s own attorney general.

If you are ever, say, stuck at home for months on end, you can always kill a few hours scrolling through the legal opinions on your state attorney general’s website. Ours usually produces a few head-scratchers per month, always prompted by some legal question from a local government official.

Some of the opinions are just quirky and interesting reads. Earlier this year, Wilson’s office weighed in on whether dry needling falls within the scope of chiropractic medicine for regulatory purposes (a staff attorney opined that it probably doesn’t). The office advised that it would probably be fine, legally speaking, for a nonprofit organization to start prescribing eyeglasses for students in high-poverty schools.

And then there are documents like this one from Dec. 2, in which a pair of state lawmakers sought an opinion on Columbia’s city ordinance banning firearms within 1,000 feet of any school building. Here’s what an assistant attorney general wrote in the conclusion of his opinion:

This Office has reiterated in numerous opinions that it strongly supports the Second Amendment and the right of citizens to keep and bear arms … Thus, the Columbia ordinance not only undermines state law, but undercuts the Second Amendment.

In January, Wilson’s office took the additional step of suing the City of Columbia over its mild gun control laws. Our tax dollars at work, folks.

The news of Wilson’s coronavirus meddling last week sent me on a trip down memory lane.

Wilson won his first election as attorney general in 2010 and took office in 2011. In 2012, he spent months claiming to anyone who would listen — including Fox News — that South Carolina had a problem with “zombie voters.” He claimed that at least 900 dead people’s identities had been used to cast votes in South Carolina, and the legislature ran with that figure when it pushed through a “voter ID” law that disenfranchised many of the state’s poor and rural residents.

But a 13-month investigation by the State Law Enforcement Division, completed after the voter ID law passed, found precisely zero instances of so-called zombie voting in South Carolina. To quote Wilson’s stepdad, Congressman Joe Wilson, “You lie!”

Early in my career as a local news reporter, I knew Alan Wilson as the guy who fought to defend South Carolina’s constitutional amendment banning gay marriage long after other states had dropped their defenses.

In October 2014, more than a year after Wilson was named as a defendant in the Bradacs v. Haley court case seeking legal recognition for same-sex marriages, Wilson’s office told me they had no way of calculating how much money or how many billable man-hours had been expended defending the obviously doomed state ban. A federal judge struck down the ban in Condon v. Haley in November 2014, but Wilson kept up the fight anyway.

In August 2015, the same federal judge ordered Wilson’s office to pay $135,276 to cover the legal fees of the plaintiffs in Condon v. Haley. This money came from taxpayer funds, in addition to whatever we wasted bankrolling Wilson’s defense of the indefensible in the previous two years. The party of fiscal conservatism is, it must be said, profligate when it comes to funding religious crusades.

The final years of the Obama administration saw Wilson distinguishing himself as a foremost opponent of rights for LGBT people. In December 2015, when transgender bathroom hysteria gripped the American right wing, Wilson signed on to an amicus brief opposing transgender students’ access to public school restrooms appropriate to their gender.

With the election of Donald Trump in 2016, Wilson immediately started pressuring the White House to ratchet up its cruelty against immigrants. He joined several other Republican attorneys general in threatening to sue the Trump administration if it did not rescind the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program and start prosecuting people who were brought to the country illegally as minors.

And who could forget Wilson’s January 2019 declaration that marijuana was “the most dangerous drug” as part of an argument against legalizing medical marijuana prescriptions? How sweet it was to see him come in for a round of mockery by libertarians and liberals alike.

I encourage you to take a look at your state attorney general’s office and keep tabs on what they are doing in your name. As the New York Times documented in 2014, attorneys general are susceptible to corporate influence peddling via the Republican Attorneys General Association and Democratic Attorneys General Association, and it takes public scrutiny to dig out conflicts of interest.

So keep an eye out. Vote for better candidates. And if you feel like crying, find a reason to laugh instead.