I hear you cussing and I’m not convinced

On the pop psychology of swear words, honesty, and self-help bullshit

One time I heard a guy say a curse word during Bible study and I was nineteen years old and it blew my damn mind.

My first response was revulsion: You can’t say that while we’re discussing the book of Acts!

Then the shock wore off and I thought to myself, he really means it. I don’t remember the exact word or even the context, but my friend was making an emphatic point about some piece of Christian doctrine or another, and he was probably right.

I was not what you would call an early adopter of curse words. I was what you would call a church kid, a goody two-shoes, a bit of a prude.

Setting aside the Bible’s imprecatory psalms, lurid narrative bits, and the Apostle Paul’s use of a word that could reasonably be translated as “shit,” I was convinced that the scriptures took a hard line against cursing, even if I couldn’t point out the exact chapter and verse to prove it.

Now I’m older and saltier and I enjoy a good cuss. There is really no replacing the catharsis of a simple “fuck!” or the comedic impact of a coinage like “shitbird.”

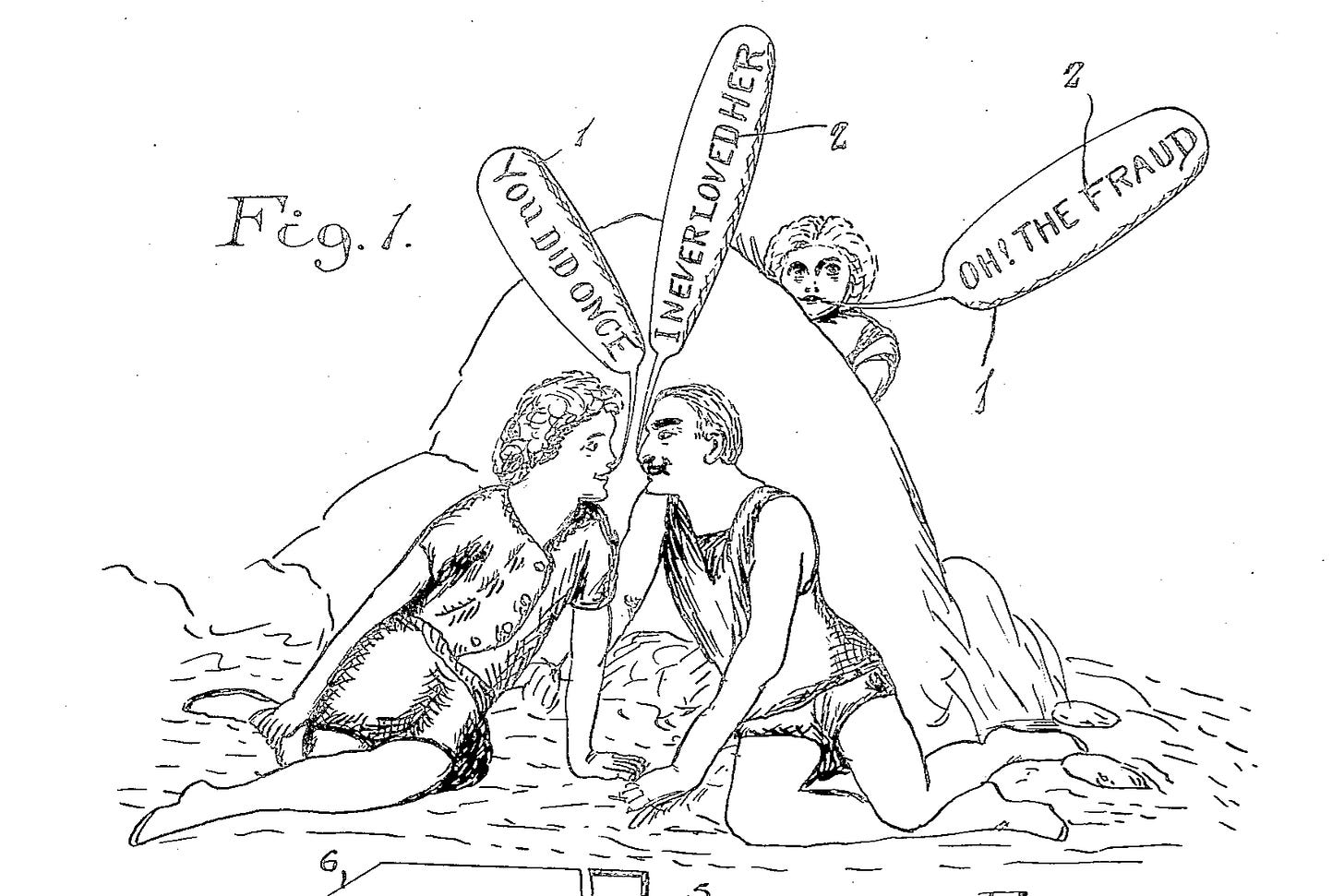

Here lately I’ve been souring on curse words, though, and it has nothing to do with my theology or Victorian sensibilities. It has to do with a cynical application of profanity that I’ve noticed in books and professional meetings and everyday conversations.

I am talking about the use of profanity to establish credibility, and I think I know where it started.

***

You may have noticed a rash of clickbaity pop-science articles in the last two years about a supposed link between profanity and honesty. Let’s play the highlight reel:

“Study finds links between swearing and honesty” (Phys.org)

“People Who Swear May Be Happier, Healthier And More Honest” (Huffington Post)

“People who swear more are more honest, new psychology study finds” (The Independent)

“The Case for Cursing” (New York Times)

The headlines were misleading at best. I recently dug up the actual study they’re all referring to, published in January 2017 in Social Psychological and Personality Science under the title “Frankly, we do give a damn: The relationship between profanity and honesty.”

In the literature review, the authors noted that the use of profanity might be linked to perceived honesty only in certain contexts.

Broadly, studies have shown a link between the use of curse words and a set of personality traits known as the “dark triad”: narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy (Holtzman, Vazire, & Mehl, 2010; Sumner, Byers, Boochever, & Park, 2012). In general, the authors noted, “people who swear are perceived as untrustworthy” (Jay, 1992).

There are exceptions to that rule. In one previous study (Rassin & Heijden, 2005), test subjects were asked to read the testimony of a person who denied committing a crime. In cases where the testimony included curse words, the subjects tended to find the testimony more credible. And at least one textbook on criminal interrogations (Inbau, Reid, Buckley, & Jayne, 2011) claimed that innocent suspects are, in fact, more likely to curse in their denials than guilty suspects.

So, if you’re facing criminal charges, the pop psychology of cussing-as-truth-telling might apply to you. Otherwise, beware.

***

The 2017 study, the one that generated all the headlines, had three parts to it and they were all pretty flawed.

In the first part, researchers asked 276 participants to list their favorite curse words and self-report how often they swear. Then the researchers assessed the participants’ honesty using a tool called the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire - Revised, which included questions like “Are all your habits good and desirable ones?” and “If you say you will do something, do you always keep your promise no matter how inconvenient it might be?”

“In these examples, positive answers are considered unrealistic and therefore most likely a lie (α = .79). The lie scale was reversed for the honesty measure,” the authors wrote.

So honesty in this context means telling the truth even if it makes you look bad. This is a type of honesty that might conceivably correspond with swearing, which still carries a slight taboo. The study found in this section that honesty was positively correlated with all self-reported profanity measures.

The second and third parts of the study, respectively, used a sample of Facebook users’ status updates and compared them with some loose measures of public integrity in U.S. state governments. Both sections found a positive relationship between profanity and honesty, but I don’t put a lot of stock in them.

I won’t bore you with the details, but a team of seven researchers issued a thorough rebuttal (de Vries, 2018) in a subsequent issue of Social Psychological and Personality Science.

I’ll let the scientists throw the shade here:

If Lie and Impression Management Scales continue to be used as indicators of dishonesty—despite the evidence that they are actually somewhat predictive of higher honesty—then scientists and the public will continue to be misinformed about the relations between actual honesty and important real-world variables, such as the use of profanity.

***

All those clickbait articles you saw about cursing and honesty fall into the same genre of feel-good science reporting as “Red wine is actually good for you.” The gist of the genre is that science has vindicated some behavior that you feel guilty about.

Here’s my theory: A whole generation of ad men, self-help hucksters, and public-relations types has absorbed the popular wisdom on cursing and used it to hawk their wares. We are living in the rootin’, tootin’, cussin’ reality they created for us, and personally I find it is sucking all the joy out of profanity.

A handful of academic papers before 2017 cast cursing in a positive light, quickly seeping down into the world of management science. See, for example, Forbes magazine’s 2011 article “The Case for Cursing,” which includes vaguely Nietzschean proclamations like “Claiming the Right to Swear is Claiming Power.”

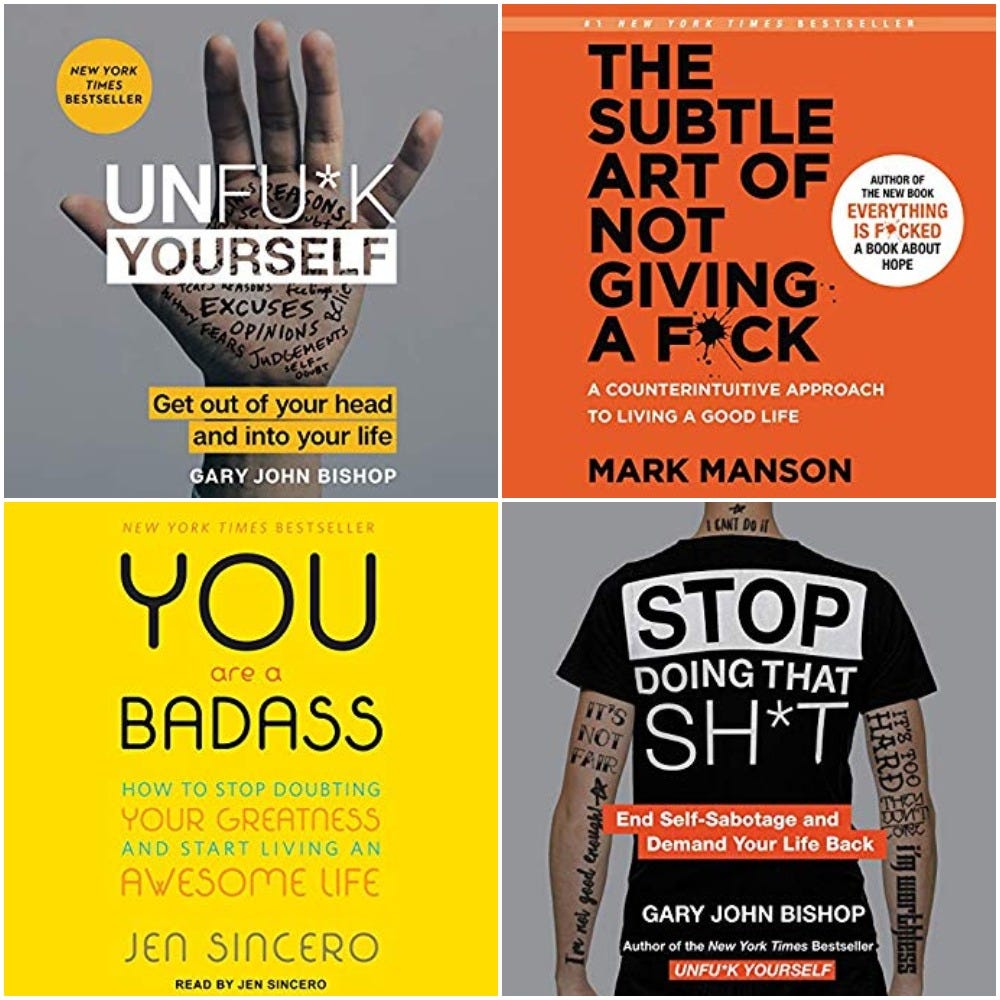

The most obvious place to observe this top-down social contagion is the self-help section of your local bookstore or on amazon dot com, which includes titles like these:

I can’t be bothered to read any of these books, but just looking at the covers (I know, I know), doesn’t the gimmick strike you as transparently manipulative?

I’ve seen the gimmick of coy vulgarity in action. When I was working as a reporter these last few years, public relations professionals would sometimes ask to meet up at a nice coffee place, where they wanted to really lay the cards on the table and cut the bullshit. This was particularly funny when the topic was, say, elementary special education and they wanted to impress me with their performative use of the word “shitshow.” I wasn’t impressed.

Maybe my theory is off base and we’re just going through a general period of language coarsening. I have another theory which is that our society is running the old taboo words into the ground so that the new taboos — slurs based on identity, sexuality, and race — can retain their potency.

Writing in his 1990 book The Mother Tongue: English and How it Got That Way, the English polymath Bill Bryson spent an all-too-brief chapter considering the history of cursing. He made the point that the severity of swear words followed the mores of the times, which explains why religious profanity used to carry a lot more weight.

“Until about the 1870s it was much more offensive to be profane,” Bryson wrote. “God damn, Jesus, and even Hell were worse than fuck and shit.”

I could be wrong, but maybe our grandchildren will roll their eyes at the faux-transgression of titles like The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck. Maybe they will see right through our bullshit. I hope they do.

***

Sources:

Feldman G., Lian H., Kosinski M., Stillwell D. (2017). Frankly, we do give a damn: The relationship between profanity and honesty. Social Psychological and Personality Science. Advance online publication.

Holtzman, N. S., Vazire, S., & Mehl, M. R. (2010). Sounds like a narcissist: Behavioral manifestations of narcissism in everyday life. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(4), 478–484.

Inbau, F. E., Reid, J., Buckley, J., & Jayne, B. (2011). Criminal Interrogation and Confessions (5th ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

Jay, T. (1992). Cursing in America: A psycholinguistic study of dirty language in the courts, in the movies, in the schoolyards and on the streets. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Rassin, E., & Heijden, S. V. D. (2005). Appearing credible? Swearing helps! Psychology, Crime & Law, 11(2), 177–182.

Sumner, C., Byers, A., Boochever, R., & Park, G. J. (2012). Predicting Dark Triad Personality Traits from Twitter Usage and a Linguistic Analysis of Tweets. Proceedings from ICMLA ’12: The 2012 11th International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications, 2, 386–393.

de Vries, R. E., Hilbig, B. E., Zettler, I., Dunlop, P. D., Holtrop, D., Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2018). Honest People Tend to Use Less — Not More — Profanity: Comment on Feldman et al.'s (2017) Study 1. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(5), 516–520.