George Floyd’s murder was not a sacrifice

On the spectacle of police killing and Nancy Pelosi’s perverse reading of Christian doctrine

The pastor stood by the church doors holding a basket full of dull iron nails. It was Good Friday, the day Christians remember the execution of Jesus, and he wanted us each to take a nail home as a reminder.

As I shuffled up the aisle that evening several years ago, I reached my hand toward him, and he pressed the tip of a nail into my palm. My fingers folded around the nail, and he looked me in the eyes and told me to go in peace.

Christian tradition is shot through with visceral reminders of torture and death: crucifixes, hymns about fountains filled with blood, even the bread and wine of communion. Especially in the evangelical and neo-Calvinist traditions that hold sway over every facet of culture and government in the U.S., the cross stands for sacrifice.

One interpretation of events is that Jesus, the perfect son of God, chose to sacrifice himself. By carrying his cross up a hill and consenting to be killed by the government, he took on the punishment that every sinner deserved, satisfying his father’s demand for justice. The highfalutin theological term for this interpretation of the cross is “penal substitutionary atonement.”

I don’t claim to know the personal beliefs of Rep. Nancy Pelosi, the Catholic Speaker of the House. But when I heard her describe the police execution of George Floyd as a willing sacrifice, alarm bells went off in my head.

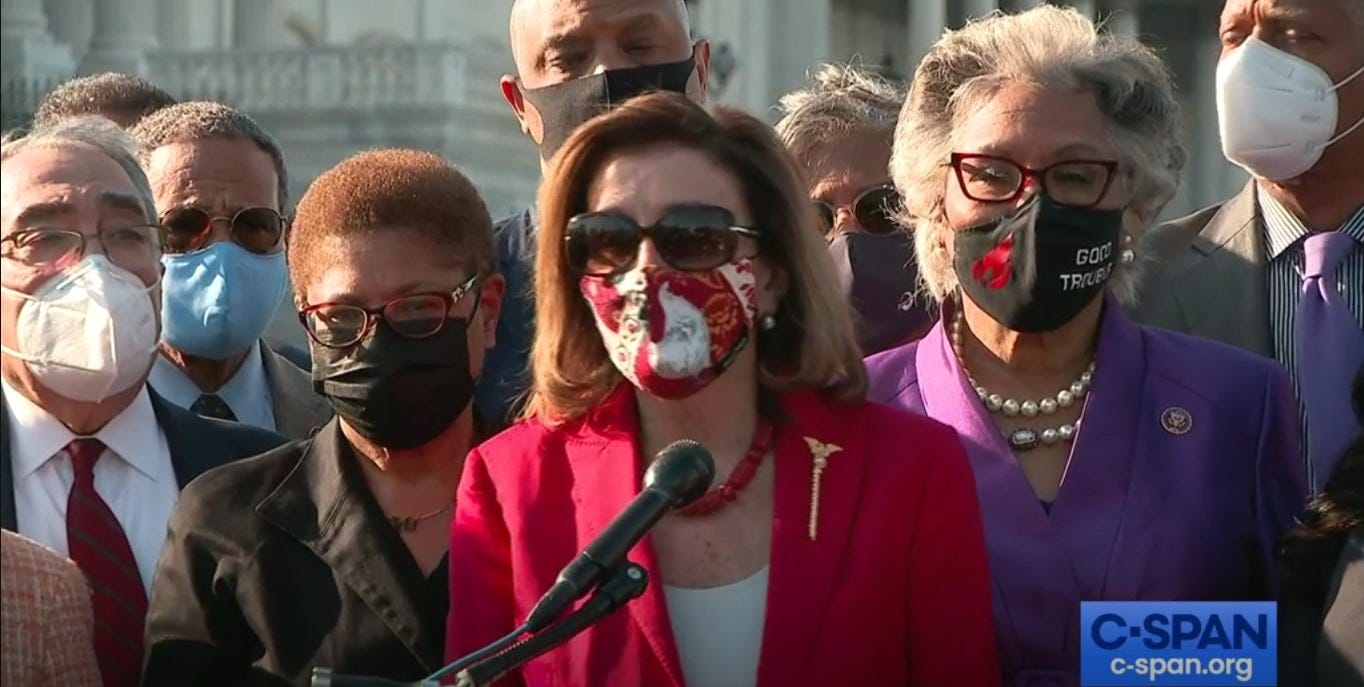

Shortly after a jury found former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin guilty of murder for kneeling on Floyd’s neck until he died, Pelosi joined the Congressional Black Caucus for a press conference. You may have seen a clip of her comments, but the full statement is even more bewildering:

Earlier, around 3 o’ clock, I spoke to the family to say to them, ‘Thank you. God bless you for your grace and your dignity, for the models that you are, for appealing for justice in the most dignified way.’ They are in search of justice then, and now, now they see this giant step, but as our colleagues have said, it’s not over …

Gianna, the little girl, his daughter, Gianna gets to see this justice on behalf of her father, his name synonymous with justice and dignity and grace and prayerfulness — and prayerfulness. So we thank God, we thank Jesus, because we were praying to him all along, right, Donna? We thank God. They are people of faith …

A little while later, she cast her eyes skyward and said:

So again, thank you, George Floyd, for sacrificing your life for justice, for being there to call out to your mom — how, how heartbreaking was that? — call out for your mom, ‘I can’t breathe.’ But because of you, and because of thousands, millions of people around the world who came out for justice, your name will always be synonymous with justice.

In what could only have been a prepared remark, she stood in front of a crowd of Black colleagues and thanked George Floyd as if he chose to be murdered by a cop.

She was doing a bit of maudlin public theologizing. As I watched her speak, I remembered something the Black liberation theologian James Cone wrote in his 1975 book God of the Oppressed: “[T]heologians must ask, ‘What is the connection between dominant material relations and the ruling theological ideas in a given society?’ ”

The language and logic of sacrifice are so pervasive in American history and culture, it’s easy to forget that they come from religious doctrine. War hawks remind us regularly that “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” (They usually leave off Thomas Jefferson’s next sentence, “It is natural manure.”)

A religion founded on death and resurrection always runs the risk of fetishizing death itself. In her 1973 book Suffering, the German liberation theologian Dorothee Sölle pointed out two tendencies that she described as “Christian masochism” and “Christian sadism,” which respectively celebrated personal suffering and the suffering of others. After all, if suffering brings about faith, redemption, grace, and justice, then shouldn’t we welcome more suffering?

“The ultimate conclusion of theological sadism,” she wrote, “is worshiping the executioner.”

Sölle reiterated the ancient call for Christians to stand in solidarity with suffering and oppressed people, but she gave a word of warning:

Gratuitous solidarity with the afflicted changes nothing; precise knowledge that such suffering could be avoided becomes our defense against addressing it. Only our own physical experience and our own experience of social helplessness and threat compel us “to recognize the presence of affliction.” Our experience of anachronistic suffering, that objectively need no longer exist, alters even our understanding of time. It strips us of all superiority that grows out of a feeling of progress and puts us in the same time-frame with the one who is suffering anachronistically. We can only help sufferers by stepping into their time-frame. Otherwise we would only offer condescending charity that reaches down from on high.

Particularly on a screen, at a distance, images of suffering and dead Black people can inspire anger or resignation. In darker moments, viral videos of Black people being murdered in the street can take on the perverse quality of lynching souvenirs.

There is no easy resolution to the theological and political problems surrounding the crucifixion. For better and for worse, Christian doctrine is still woven through our secular institutions of democracy, justice, and penology. The doctrines run the risk of warping those secular institutions, and the institutions run the risk of warping the doctrines.

In the preface to the 1997 edition of God of the Oppressed, Cone responded to some of the critiques he received after his book’s initial publication. He identified the relationship between suffering and faith as the central dilemma of Christianity:

If God is liberating blacks from oppression, why then are they still oppressed? Where is the decisive liberation event in African-American history which gives credibility to black theologians’ claim? There is no easy response to this critique, since there is no rationally persuasive answer to the problem of theodicy. Faith is born out of suffering, and suffering is faith’s most powerful contradiction. This is the Christian dilemma. The only meaningful Christian response is to resist unjust suffering and to accept the painful consequence of that resistance.

More deaths won’t bring about more justice. Struggle will. Solidarity will. For those who believe, we know that Jesus came down from the cross, and he stands with us when we stand with the oppressed.

***

Brutal South is a free weekly newsletter and podcast that publishes every Wednesday. For $5 a month, you can help support my work and get access to subscriber-only newsletters and podcast episodes.

A few weeks ago, my pastor asked me to write a short reflection on the crucifixion for Holy Week. I wrote about capital punishment and Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane. You can read it here if you like.

Twitter // Bookshop // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts