Existenzminimum

Thoughts on a ‘wonderful little spot that we entrepreneured’

Existenzminimum is one of those concepts you start to see everywhere once you hear about it.

The idea came about during a housing crisis in Germany after World War I. The 1919 Weimar Constitution guaranteed the right to a “healthy dwelling” for every German. Members of the New Objectivity movement fleshed that promise out in the architectural-political concept of Existenzminimum.

Literally, the word translates to “subsistence dwelling,” but that doesn’t capture the scope of the radical social project. Existenzminimum “set the conditions for a dignified and healthy existence, including access to food, clothing, medical care, and housing, assured by a defined minimum level of income,” according to Sara Brysch, architect and researcher at Delft University of Technology.

The technical definition included quality building standards as well as access to natural light and green spaces, guaranteed by a new democratic welfare state. In some cases the government found it needed to build smaller, more densely packed housing to efficiently house everyone in a community; in other cases it found that the existing housing stock was much too small and would need to be replaced with bigger homes for families.

The Weimar Republic notably failed in horrific fashion. But the social-democratic values it promoted proved to be hugely influential in industrialized countries, particularly in the area of social housing via the Bauhaus school. Today we hear echoes of Existenzminimum everywhere from the alluring and well-built public housing projects of Scandinavia to their consumerist facsimiles in the IKEA catalog. Notably, the winners of this year’s Pritzker Prize in architecture, Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, made their name designing social housing projects.

The word Existenzminimum doesn’t translate well into American English because we have never had a similar concept of collective good in this country. Instead of a universal good for the dignity of all people, we think of housing as a luxury good (to say nothing of healthcare, education, food, green space, or transportation). At best, our approximations of the idea end up reading like a sick parody.

No one, in any state, can afford a two-bedroom apartment while working full-time on the $7.25 minimum hourly wage guaranteed to workers in the United States. In 93% of U.S. counties, minimum wage isn’t even enough for a one-bedroom according to the latest report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition. And that’s according to an “affordability” threshold set at 30% of a renter’s income, as opposed to the 25% standard set under the German Existenzminimum.

Instead of quality housing for all, we have housing situations like … uh, this:

There’s a viral TikTok video going around of an eager young techbro giving a tour of a 4-story brownstone mansion somewhere in New York City that he shares with “15 other entrepreneurs that I met online.”

On the first floor we see a mattress shoved under a staircase with Christmas lights strung up over it to create a sort of charming Harry Potter bedroom.

“We only really did that because we don’t have that many bedrooms for all 16 of us,” he explains.

On the second floor, the cameraman notes, “we’re having some issues with kitchen cleanliness,” but don’t worry! someone has installed a security camera to keep tabs on the roommates.

Then there’s a bed on top of a closet for someone named Riley. The cameraman climbs an aluminum ladder and peeks over the top.

“His room is between the closet and the ceiling here, so — wonderful little spot that we entrepreneuered,” he announces.

“This is Grind Central USA,” he says of a room with three visible beds and a work desk.

It’s like an upscale war hospital, and probably a violation of fire codes. The guy who uploaded the video (@willyhopps) has since deleted it, so he might be in hot water with his landlord for “entrepreneuring” too many people into a sublease.

Unlike @willyhopps, most Americans aren’t devising whimsical lofts in a 4-story New York brownstone. The housing situation out here is dire.

***

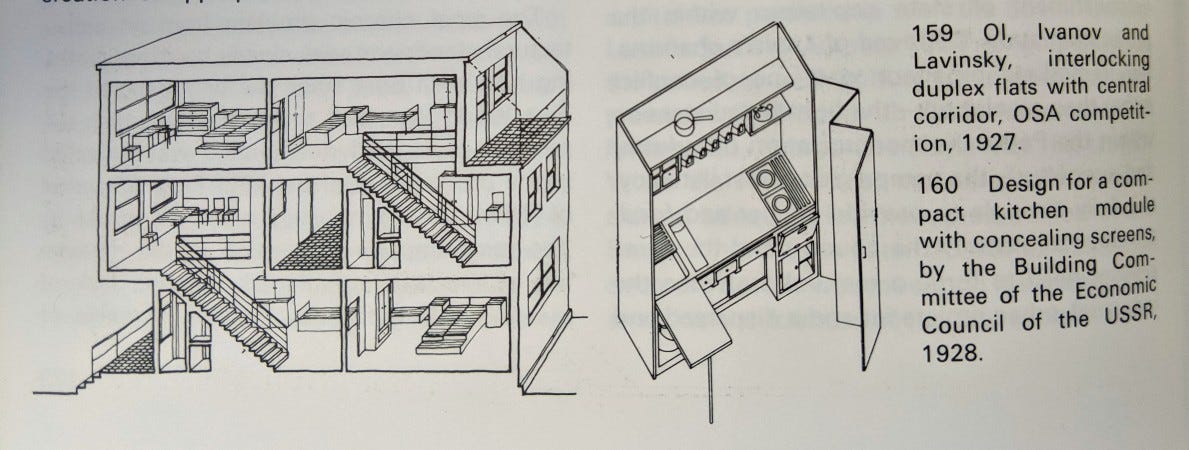

The notion of Existenzminimum, developed in parallel with the Soviet concept of dom-kommuna, was hugely influential for modern architects. Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius folded some of its key concepts into the International Style.

But capitalists quickly ground off the idealistic bits and repurposed the aesthetics: There is no guaranteed human right to decent housing in the U.S., but you can buy the look of the modernist dream at IKEA or Target or West Elm.

Brysch writes:

[A]ll these progressive and rational visisions towards housing production turned the house into a product, and the dweller into a consumer. In the following decades, the minimum dwelling unit--small, cheap, easy to build--became the gold mine of the capitalist housing market, and started to be reproduced and sold as commodity, as an isolated element, originating the real estate logic of the city.

Brysch asserted that the concept of Existenzminimum could be revived to useful ends in a context of holistic urban planning, particularly in light of the ongoing climate crisis. She reviewed a few community-planned living arrangements in European countries in the early 21st century, but notably none in the United States.

Over here, you can see vestiges of Existenzminimum in Instagrammers’ vague romanticization of “tiny houses” or in ad copy for enclosed “communal” spaces within a private housing development. You catch a sad whiff of it when you read about workers paying $2,400 a month to live in San Francisco adult “dormitories” while outside their windows the city allows a rate of homelessness that the U.N. has deemed a human rights violation.

Where once we had Le Corbusier devising housing as a “machine for living in” and Buckminster Fuller creating the modular marvel of the Dymaxion House, now we have tepid entrepreneurial advances like this slow, dangerous, electric-powered Murphy bed:

Allergic to any form of central planning, we leave the provision of affordable housing to the entrepreneur class, who have proven themselves wildly inept at the task.

That’s how we get three-car pileups of bad ideas like this one:

The Colorado Sun reports:

FLORENCE — Past downtown’s hip coffee shop and brewery, across the street from a gravel pit and next door to a long abandoned house, a Lego-like solution to Colorado’s housing crisis is taking shape.

“Everything you see in here was recycled or it can be recycled,” said Wyatt Reed, swinging open the doors to a 40-foot shipping container.

Inside the metal box is a plush home, with insulated walls, re-used cabinets, trim from local barns, salvaged doors, decorative tiles made from melted down garden plant containers and lockers from the high school. Reed and his business partner, Barna Kasa, buy the shipping containers for about $4,000 and convert them into homes. Their business plan calls for eventually selling the move-in-ready homes for $50,000, and a bit more for units that ship inside the container and are assembled on top, offering nearly two-times the space.

“I call it Ikea meets Uber for homebuilding,” said Reed, leaning back on the railing of his rooftop patio.

“Ikea meets Uber for homebuilding” is one of those phrases you really have to swish around in your mouth before spitting it out.

Also, the base price of $50,000 for a modified shipping container (320 square feet) is not much less than the going price for a single-wide mobile home (500 to 1,200 square feet). And even if you can cram yourself and your loved ones into it, you still have to own or rent land to put it on. So it’s not clear which part of the affordable housing crisis these homes are meant to solve.

If anything, they’re lowering the bar for subsistence.

***

Brysch, Sara. “Reinterpreting Existenzminimum in Contemporary Affordable Housing Solutions.” Urban Planning, vol. 4, no. 3, 30 Sept. 2019, pp. 326–345., doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v4i3.2121.

Frampton, Kenneth. Modern Architecture: A Critical History. Hudson and Hudson, 1992.

Twitter // Bookshop // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts