Brutal South Roadtrip: Tuskegee

Chapel acoustics, phenomenology of space, and the Le Corbusier of the Deep South

I’m writing a book about brutalist architecture in the American South, and the more I research, the more I want to take a roadtrip.

Once my family is vaccinated and the coast is clear, I would love to take in a show at Houston’s Alley Theatre and kvetch about the renovations at Atlanta’s Central Library. Heck, I’m so starved for new scenery I could go for a little sightseeing at the Miami-Dade County School Board Administration Building.

The book project is in an early phase. I recently received some funding via the Lowcountry Quarterly Arts Grant to help pay photographers across the region for their work, and I’ve been talking to a few publishers who expressed an interest. I’ll keep you posted.

As I assemble a list of buildings and architects to feature, I know I won’t get to see every building in person, during a pandemic or not. But there are some experiences that seem worth the drive.

My current obsession is Paul Rudolph’s 1969 chapel at Tuskegee University in Alabama.

It’s an awkward fit for a book about brutalism. It’s not nearly as stark as Marcel Breuer’s St. Francis de Sales Church, and it’s dwarfed by Gottfried Böhm's mountainous Church of the Pilgrimage in Neviges. It lacks one of the most obvious hallmarks of brutalist architecture: exposed concrete walls. The walls of the Tuskegee chapel are instead rendered in red bricks made of Alabama clay.

I would like to gain a better understanding of this chapel. To do that properly, I think I need to go inside and hear the choir sing.

The story of how Rudolph came to design a chapel for a small historically black college at the peak of his career is worth telling at length one day, but the short version is this: Tuskegee’s original 1898 chapel by the trailblazing Black architect Robert Robinson Taylor burned down one night in January 1957, purportedly due to a lightning strike. Rudolph, who had attended the nearby Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University), got hired to design a replacement alongside ex-Tuskegee faculty members Louis Fry and John A. Welch.

The original 1898 chapel was a landmark. Built with student labor from local bricks, it was the first building in Macon County with indoor electric lights. The replacement had to live up to that legacy somehow.

During the 10 years of the chapel’s design and construction, Rudolph was working on his most iconic brutalist designs elsewhere, including the Government Services Center in Boston and the master plan for the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. In keeping with his style at the time, Rudolph intended to build the Tuskegee chapel out of concrete too.

According to Karla Cavarra Britton and Daniel Ledford (Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Sept. 2019), the architect Major Holland was working on the ground as Fry & Welch’s representative in Tuskegee when he made some judgment calls. He added a 96-foot steel beam to support the roof above the outside pulpit, and he chose “local salmon-colored brick” rather than concrete as the main building material.

“Holland chose the brick in part for economic reasons, but also because the use of brick was in keeping with Tuskegee’s long tradition of brick making and bricklaying,” Britton and Ledford wrote in their paper “Paul Rudolph and the Psychology of Space: The Tuskegee and Emory University Chapels.”

One crushingly brutalist element remains: the 71-ton parabolic roof that looms over the edges of the chapel, swooping down toward the interior pulpit and choir area. I imagine standing under it and pondering its bulk is one way to summon up the fear of God.

With the daring, asymmetrical chapel roof in Tuskegee, Rudolph was paraphrasing Le Corbusier’s 1954 Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France. But he was also drawing on memories of his own father’s career as a Kentucky Methodist minister. Rudolph grew up hearing sermons and feeling the thrum of hymnsong in his chest.

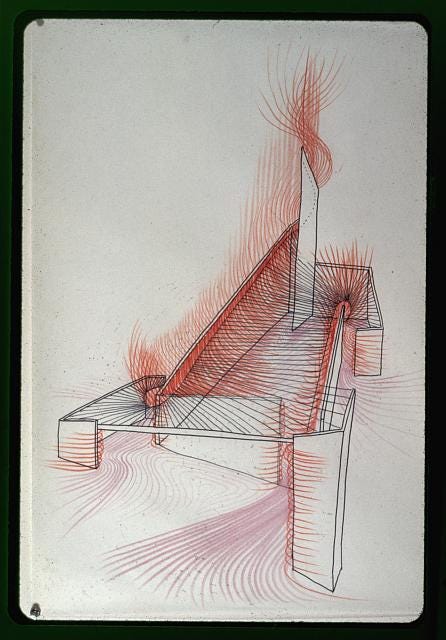

When Rudolph sketched the chapel, he included shafts of light, but he also drew nebulous lines of movement along the edges, representing either acoustic properties or something ineffable. He had a peculiar way of describing movement in the interior:

The roof is hyperbolic paraboloid in form for acoustic reasons, and the space rises diagonally and escapes through glass. The directions of the movement of space are in opposite but balanced directions, which is largely responsible for the dynamic quality of the space. In addition, there is a varying velocity of the movement of space. The floor is almost level, but the ceiling height above the floor constantly changes, so that the space moves rapidly where the ceiling is high but more slowly where the ceiling is low. All of this must be imagined, so that there is a balance between opposite movements of space and light.

Rudolph had a notion of “the psychology of space.” When he designed a building, he wanted to induce a particular effect in anyone who entered it.

When an interviewer asked if people would enter Tuskegee Chapel in the center of the space, Rudolph replied, “Certainly not … When you enter a large space, you must try and enter it from a corner, from one side—never in the center. Going into a space down the middle is really scary!”

I can sense myself going out of my depth here. I think that to understand Rudolph, I might need to gain a better understanding of phenomenology, the study of structures of consciousness and experience.

Reading pure phenomenology makes my brain feel like soup, but I have been trying to understand Gaston Bachelard’s 1958 book The Poetics of Space in the context of pronouncements like Rudolph’s. I see some parallel thinking about the experience of interior and exterior spaces.

Here’s a passage of Bachelard from a chapter called “intimate immensity”:

At certain hours poetry gives out waves of calm. From being imagined, calm becomes an emergence of being. It is like a value that dominates, in spite of minor states of being, in spite of a disturbed world. Immensity has been magnified through contemplation. And the contemplative attitude is such a great human value that it confers immensity upon an impression that a psychologist would have every reason to declare ephemeral and special. But poems are human realities; it is not enough to resort to “impressions” in order to explain them. They must be lived in their poetic immensity.

And then there is this snippet of a Rilke poem that Bachelard quotes in the same chapter:

Space, outside ourselves, invades and ravishes things:

If you want to achieve the existence of a tree,

Invest it with inner space, this space

That has its being in you.

What I’m trying to say here is I need to drive to Alabama, for philosophical reasons.

***

If you enjoyed today’s newsletter, you’ll really get a kick out of the recent podcast I recorded with architecture critic Kate Wagner (@mcmansionhell) on southern brutalism, Paul Rudolph, preservation, and more. Check it out here if you like, or just look up Brutal South in your podcast app of choice.

If you would like to support my work and get access to subscriber-only podcasts and newsletters, please consider becoming a paying subscriber. It’s five bucks a month.

Twitter // Bookshop // Bandcamp // Apple Podcasts // Spotify Podcasts

There’s enough material just waiting to be explored further here to justify a 45-hour college course. The 45 hours would be in addition to the field trip. It was an adventure just to read this.

Only you could make me want to jump in the car and drive to Alabama to enter a specific church from the corner. I'll never enter buildings from the middle the same again!

Love this and your brain as per. I cannot wait to own your book!