A brief history of the lynching metaphor

How powerful white people claimed the oppression of racist violence

The lynching metaphor has been abused for so long by defenders of the indefensible, I am hard-pressed to think of responsible rhetorical uses of the word “lynch.”

I’m talking about something the president said on Twitter. I generally try to avoid doing that, but I took the bait this time. So it goes.

U.S. Sen. Lindsey Graham, a Republican from South Carolina who really ought to know better, continued in his role as obsequious toady on Tuesday by defending Trump, saying on television, “This is a lynching in every sense.”

At the risk of stating the obvious, an impeachment inquiry is a lynching in no sense of the word. It doesn’t even hold up as a figure of speech.

Like the witch-hunt metaphor that Trump loves to employ, the lynching metaphor refers to ritualized acts of violence that resulted in the deaths of innocent people and terrorized others for generations.

Reading Graham and Trump charitably, you could say they are grasping at one element of lynching, the extrajudicial nature of the trial, to describe the “court of public opinion.” But even as an expression of the president’s persecution complex, the metaphor dissolves beyond that point.

Lynchings of African Americans in the South weren’t just one-off acts of spite or partisanship; they were a longstanding practice of state-sanctioned racial terrorism. Lynchings served to uphold a social, economic, and religious hierarchy whose defenders are still alive today.

Lynching enforced a racial and economic caste system that put wealthy white men like Donald J. Trump at the very top.

Trump is by no means unique in this particular manifestation of his racism. When powerful people (including, it should be said, Joe Biden) claim lynching, they invert the very meaning of the word and trample on the reality and the recency of American lynching: The last known survivor of a lynching died in 2006; the last court trial of a Ku Klux Klan lyncher took place in 2005.

Below here you’ll find a rundown of the rhetoric that paved the way for Trump’s comment, with credit due to the historian Lawrence Glickman, whose Twitter thread yesterday clued me in to several of the early instances.

Glickman described the practice of crying “lynch” this way:

“The essence of ‘elite victimization’ was the desire to take the metaphorical place of the victims of actual racial violence, while doing very little either to stem the tide of that violence or even to recognize the plight of these victims.”

Sen. Joseph McCarthy, 1954

McCarthy felt he was wronged by his colleagues in the Senate when they met in a special session in the fall of 1954 to consider censuring him for his paranoid anti-Communist antics.

Referring to his own committee’s pressing business, McCarthy told his colleagues on Nov. 4, 1954, “If it appears that [the debate] will be over before long, I might suggest waiting until the Nov. 8 lynch party is over.”

Like Trump, McCarthy seemed drawn to the sound of certain phrases and would mash the same rhetorical button over and over until it stopped getting him a response.

“I think ‘a lynching bee’ is a good name for it,” McCarthy said on a Face the Nation panel on Nov. 7.

McCarthy’s gambit was especially brazen because actual lynchings were still underway. The next year, 1955, at least three black men were lynched in Mississippi, according to the Monroe Work Today database. Their names were George W. Lee, Lamar D. Smith, and Emmett Louis Till.

Karl Rove et al., 1974

Even before Richard Nixon’s name became a shorthand for impeachable offenses, the Nixon administration found ways to cast itself as the victim. When the Senate rejected Nixon’s appointment of the Florida segregationist G. Harrold Carswell to the Supreme Court in 1970, Carswell’s defenders in newspaper editorial pages referred to a liberal “lynch mob” of labor union organizers and civil rights activists dragging poor Carswell through the mud.

In the spring of 1974, with the Watergate scandal in full bloom, a 23-year-old George Mason University student named Karl Rove created the fictitious organization Americans for the Presidency and sent out a memo alleging that the Congressmen investigating Nixon had been swept up by “the lynch-mob atmosphere created in this city by the Washington Post and other parts of the Nixon-hating media."

Rove went on to have a successful career as a political consultant, including a stint as senior advisor to U.S. President George W. Bush. The president referred to him as “Boy Genius” and “The Architect,” among other nicknames.

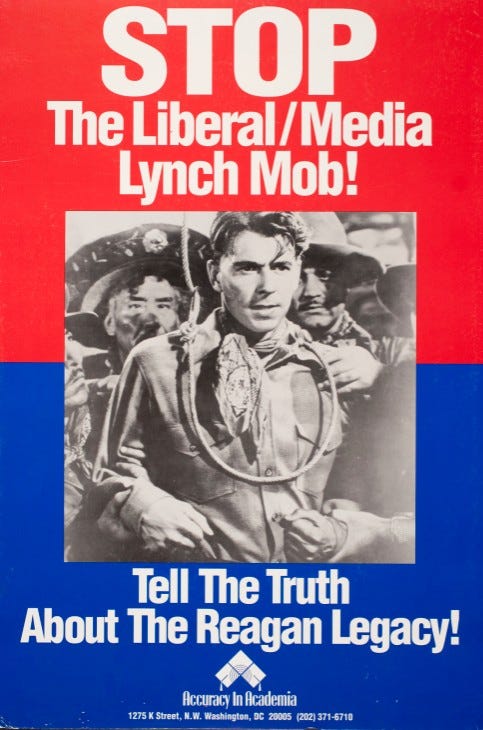

Gen. William Westmoreland, 1984

The former commander of U.S. armed forces in Vietnam said he had been “rattlesnaked” by CBS broadcaster Mike Wallace in an interview about the size and nature of enemy forces during the Vietnam War.

''I became very angry, very disillusioned,” the four-star general said during testimony in a libel case he brought against CBS. “I realized I was not participating in a rational interview — this was an inquisition. I was participating in my own lynching, but the problem was I didn't know what I was being lynched for.''

The libel case was settled out of court before it reached a trial.

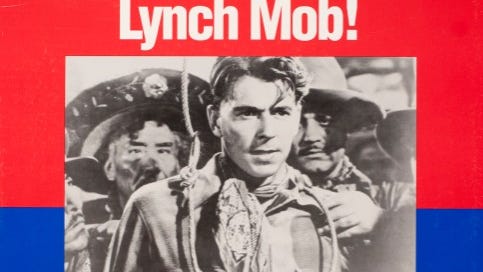

Ronald Reagan, 1986

In what is now known as the Iran-Contra Scandal, members of the Reagan administration secretly sold weapons to Iran despite an arms embargo, hoping to spend the proceeds funding right-wing militants in Nicaragua despite a prohibition on such spending from Congress.

The whole thing looked bad for Reagan, an ostensible law-and-order politician, and for Reagan’s Republican Party. So, the Associated Press reported in 1986, two major conservative groups funded a $2 million ad campaign to rehabilitate Reagan’s image by denouncing conservative “cowards” and a “liberal lynch mob” for allegedly attacking the president. They even went to the trouble of printing posters that depicted a TV cowboy with a noose around his neck.

Sen. Chuck Grassley, 1988

Grassley, R-Iowa, referred to the hearings of failed Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork as “little more than a political lynching.” Opposition to Bork’s nomination centered around his involvement in Nixon’s 1973 Saturday Night Massacre (another curious application of a violent metaphor) and his stated intention to roll back civil-rights decisions from previous courts.

President Reagan got in on the action too, referring to Democrats on the Judiciary Committee as members of a “lynch mob” for criticizing his nominee. Like Trump, Reagan was parroting something he heard in the media. He copped the phrase from “the Washington pundit David Broder,” according to the Chicago Tribune.

The venerable William Safire defended the use of the “lynch mob” trope, writing this in his column:

Amid all this, a word began to surface that was at first ignored. The word was ''lynch,'' and it was not being used just by stunned conservatives complaining about mob psychology and character assassination. The evenhanded columnist David Broder deplored a moment ''when judges are lynched to appease the public.'' The pacifist, liberal Republican Sen. Mark Hatfield of Oregon announced that he would vote to support the Bork nomination if it came to the floor because he did not like the lynch-mob atmosphere.

The charge was true: Bork had been strung up without fair process, savaged by the ACLU, AFL-CIO, NAACP, NOW powerhouse operating out of a Democratic ''war room'' in the Senate chamber. Campaign strategy was set, mailings were made, opinion polls publicized, senators lobbied, the media manipulated to feed the bandwagon psychology.

Grassley, for his part, kept using the phrase well into the new millennium.

“I think the hearing went well yesterday unless people are out to politically lynch somebody,” he said of the 2002 vetting of Thomas Dorr for an undersecretary position in the Department of Agriculture.

Clarence Thomas, 1991

Thomas’ indignant defense against claims of sexual harassment is often cited as the urtext of the metaphorical lynching genre, echoed by Brett Kavanaugh’s defenders during his own confirmation hearing in 2018.

President George H.W. Bush had nominated Thomas, an African American conservative judge, to the highest court in the land when law professor Anita Hill accused him of making explicit sexual comments in the workplace. Two other women came forward to corroborate Hill’s story. The Senate narrowly confirmed Thomas anyway in a 52-48 vote.

Thomas had this to say:

This is not an opportunity to talk about difficult matters privately or in a closed environment. This is a circus. It's a national disgrace. And from my standpoint, as a black American, it is a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves, to do for themselves, to have different ideas, and it is a message that unless you kowtow to an old order, this is what will happen to you. You will be lynched, destroyed, caricatured by a committee of the U.S. Senate rather than hung from a tree.

Conservative politicians and pundits still refer explicitly to Thomas’ defense when they bring up the lynching defense. A quick sampling from the last decade:

“Lynching Nikki Haley” (Erick Erickson, Red State, 2010)

“Ann Coulter calls allegations against Cain ‘high-tech lynching’” (New York Daily News, 2011)

“Coulter likens Zimmerman ‘lynch mob’ to another Democratic Party ‘outgrowth’: The KKK” (Daily Caller, 2012)

“Gingrich on Roy Moore: Amazing how fast 'lynch mob' can form” (The Hill, 2017)

“The Political Lynching of Brett Kavanaugh” (Wayne Allyn Root, Townhall, 2018)

Joe Biden, 1998

Biden had a front-row seat to Thomas’ confirmation hearings during his time as chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1991. He faces scrutiny to this day for the way his committee mocked and ignored Anita Hill during her testimony.

So it should come as no surprise that Biden employed the lynching metaphor in 1998 to defend his fellow Democrat, President Bill Clinton, against an impeachment involving sexual misconduct and perjury.

"Even if the president should be impeached, history is going to question whether or not this was just a partisan lynching or whether or not it was something that in fact met the standard, the very high bar, that was set by the founders as to what constituted an impeachable offense,” Biden said on CNN.

Arlen Specter, 2005

Lynching once referred to the slaughter of mostly black and minority folks for the crime of voting, or of entering interracial relationships, or of any other behavior the white elites deemed improper. By 2005, white elites were freely using the term to describe their own supposed persecution.

Sen. Arlen Specter, chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, rose to the defense of Harriet Miers, President George W. Bush’s nominee for the Supreme Court, who was facing criticisms from the Christian Right.

“She's faced one of the toughest lynch mobs ever assembled in Washington, D.C. And we really assemble some tough lynch mobs,” Specter said on ABC’s This Week.

Gode Davis and Peter Ian Asen analyzed this rhetorical turn in a 2006 issue of Against the Current. After reviewing the actual history of lynch mobs in the nation’s capital, they wrote:

Senator Specter’s use of the phrase “lynch mob”—like the emotionally charged claim by Clarence Thomas in 1991 that he was the victim of an “electronic lynching”—suggests that lynching’s bloody history has been sufficiently diluted in the American imagination so as to become mere rhetoric for political discourse.

Fourteen years after Thomas transformed “lynching” into a personal metaphor dependent upon his black skin, a political “lynch mob” can be said to descend on an elite, white, Christian woman (a seemingly unlikely lynching victim) for the “crime” of not being far enough to the right.

***

I’ll confess here that I leaned on a lynching metaphor, perhaps a bit too hard, in a recent talk on book censorship.

It was Banned Books Week, and I had recently come across this quote attributed to Henry Louis Gates, literally written on a sidewalk in my neighborhood: “Censorship is to art as lynching is to justice.” (In my haste to put together a presentation, I committed another cardinal sin and failed to find an original citation for this quote, too. Still no luck on that front.)

I thought the analogy worked on two levels: 1) Censorship, like lynching, is partly meant to send a message, to terrorize and intimidate people beyond its immediate victims, and 2) Censorship, like lynching, often requires a blend of tacit and explicit participation by government as well as private individuals.

But the analogy breaks down because no actual violence is done in the act of censorship, even when mobs throw literature on a bonfire. Even in 1835, when a vigilante group referring to themselves as the Lynch Men stole abolitionist tracts from the Charleston, S.C., post office and burned them in the street, the lynching metaphor was spread a bit thin.

I fear the return of literal lynching may not be far away. The president has been joking and winking about shooting immigrants during his rallies. “Only in the Panhandle you can get away with that statement,” he told a hooting crowd of Floridians in May.

Let’s measure the weight of the word. We may soon need to use it in its literal sense.